Curd Jürgens in the 1960s and 1970s

By Rudolf Worschech

The Media phenomenon

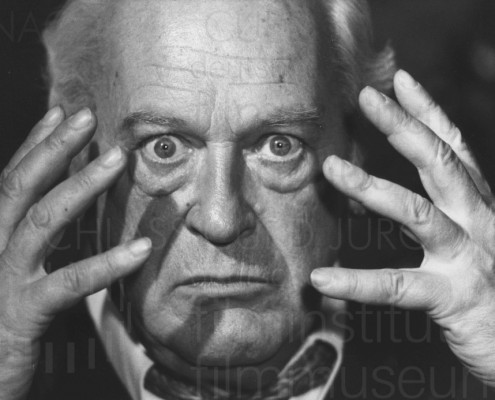

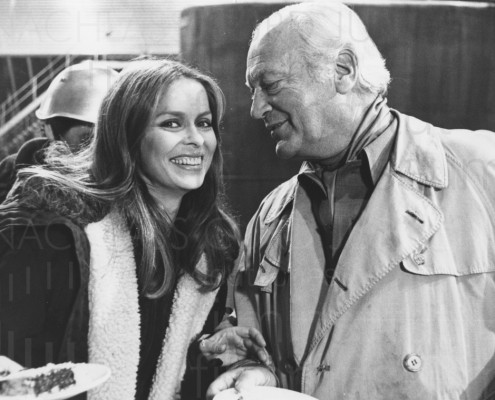

There is a famous photograph of Curd Jürgens from 1971 in which he is shown with the then West German Chancellor Willy Brandt in the garden of the Chancellor’s Office in Bonn. To the left of Brandt is Romy Schneider, visibly ill at ease; to the right is Simone Jürgens, and then Curd. The two men are roughly the same age – Jürgens was born in 1915, Brandt in 1912 – and both men are keeping their distance. Jürgens seems to be chatting, Brandt is listening. The statesman and the artist – at first sight, it is impossible to tell them apart.

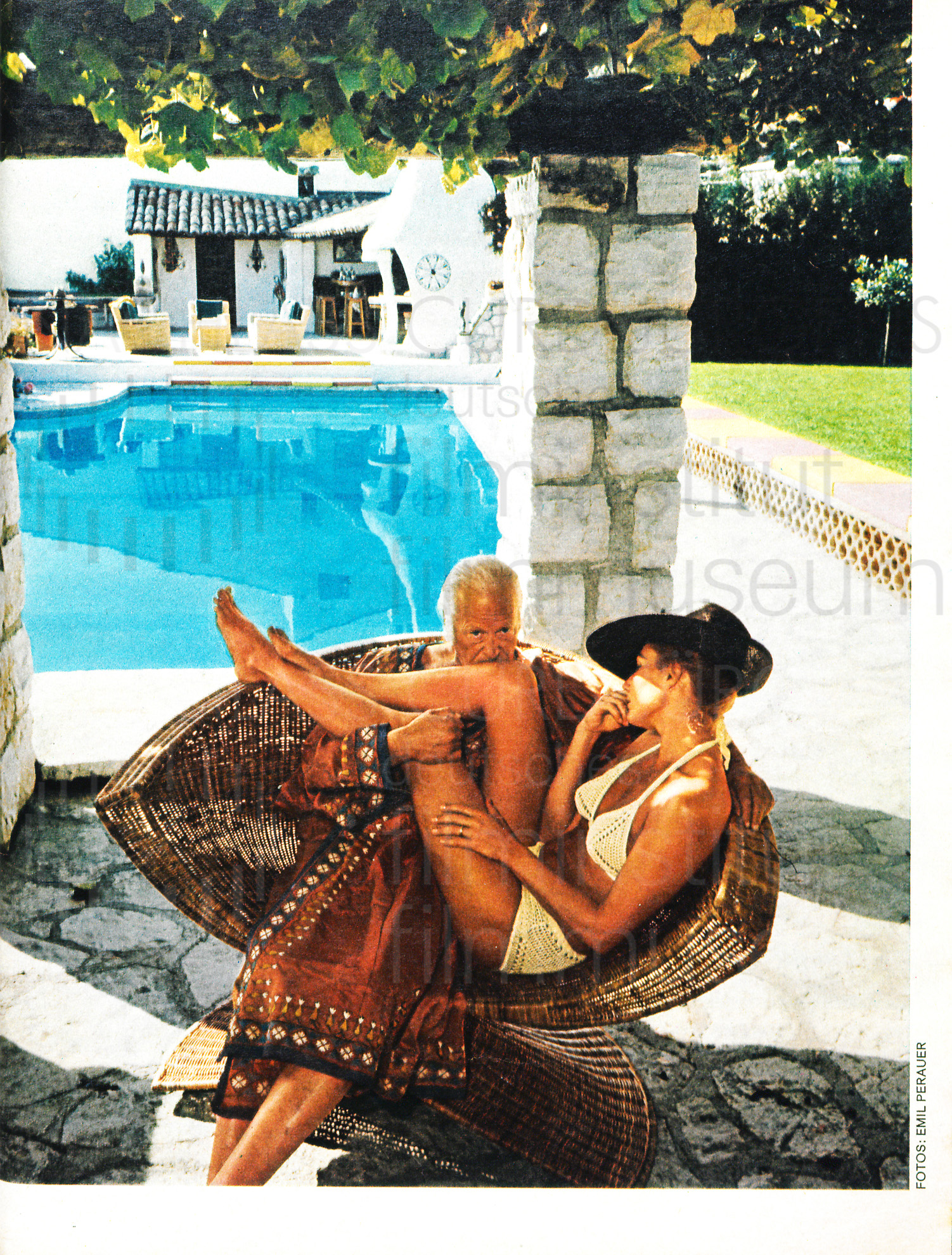

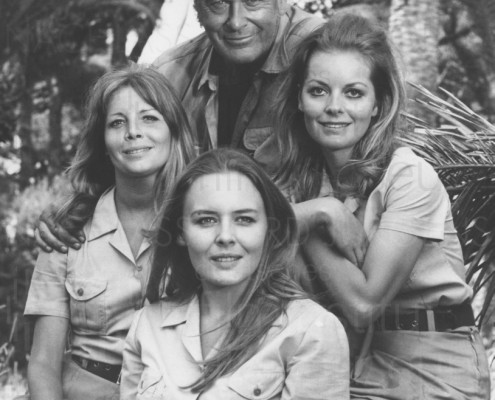

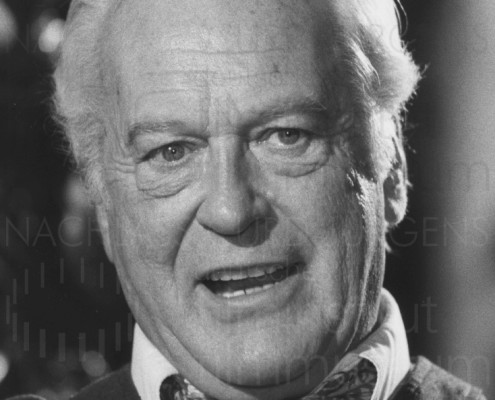

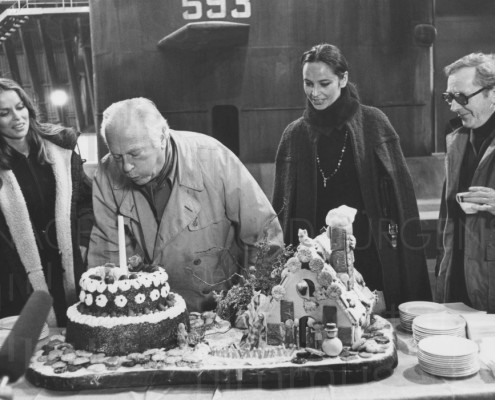

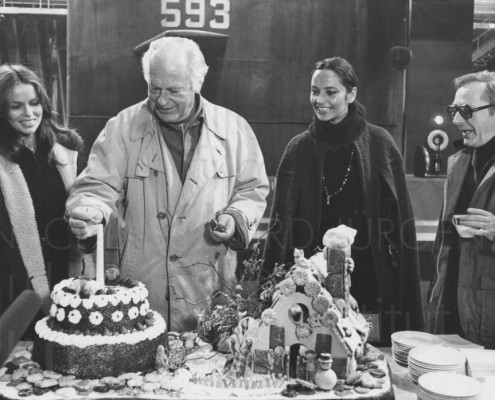

An artist? At this point, Curd Jürgens was more like a public institution. A person in whom both society and the press showed an intense interest: in his wives (Simone was the fourth); in his physical ailments (he had been suffering from heart problems since 1967); in his stays in France, Austria, Switzerland and the Bahamas; and in his fleet of cars, topped off by a Rolls-Royce and a Bentley. On the occasion of his 55th birthday on 13 December 1970, Stern magazine published a multi-part biography of the actor entitled “I, Curd Jürgens”. Film was something rather on the margins.

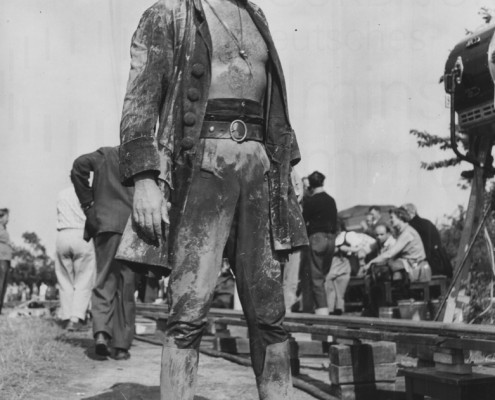

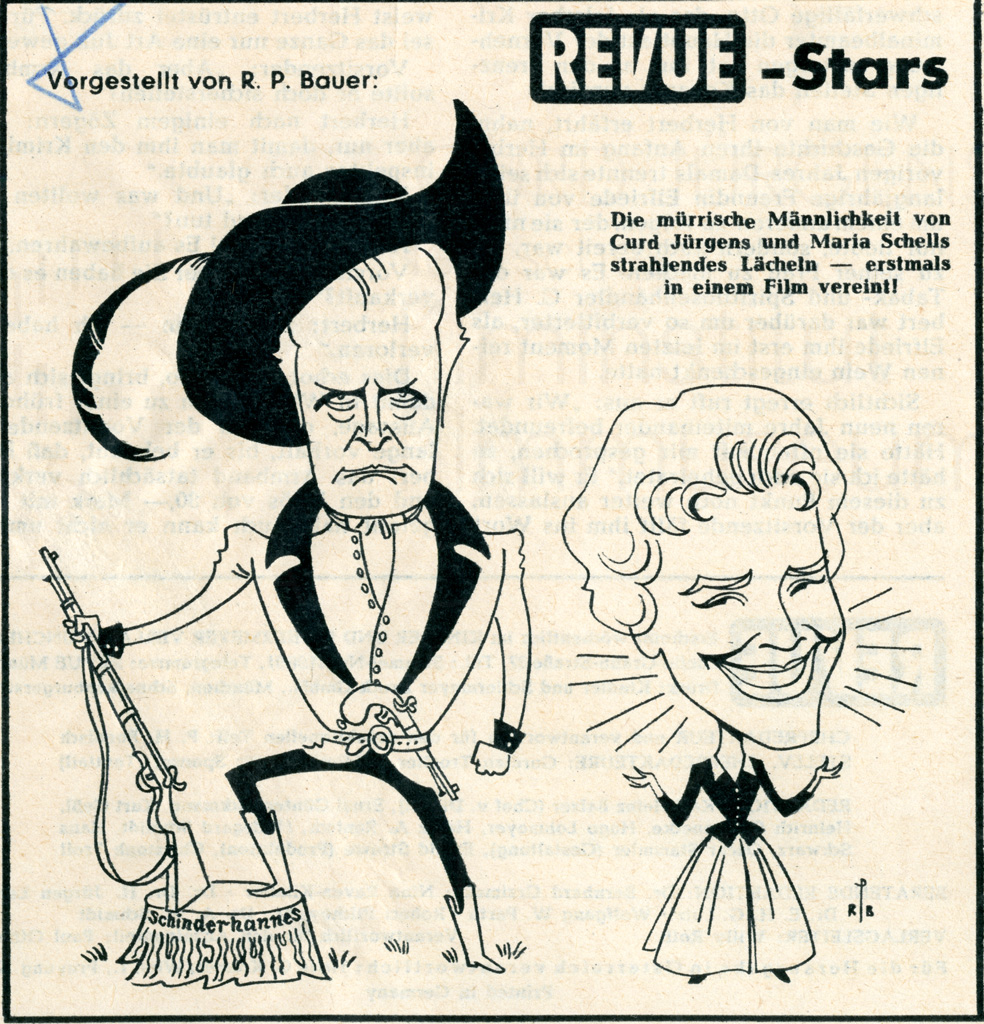

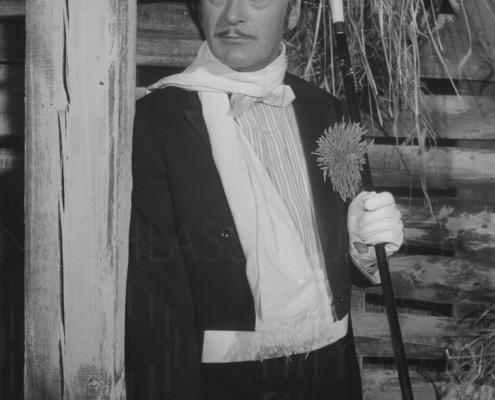

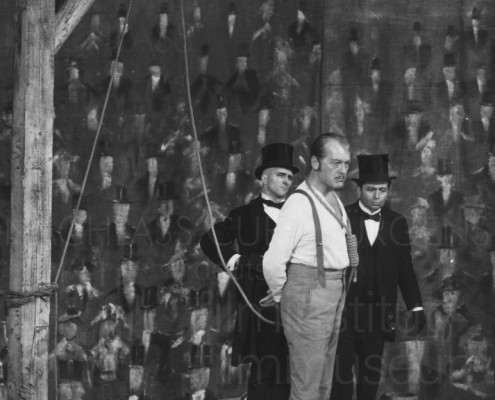

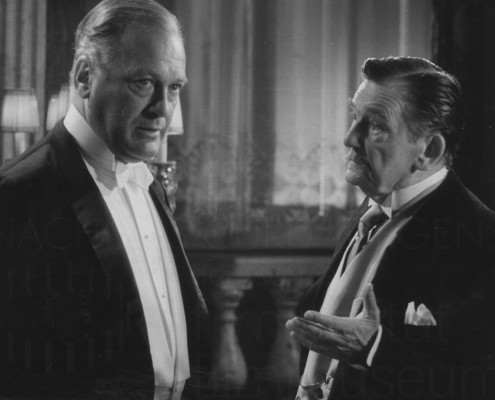

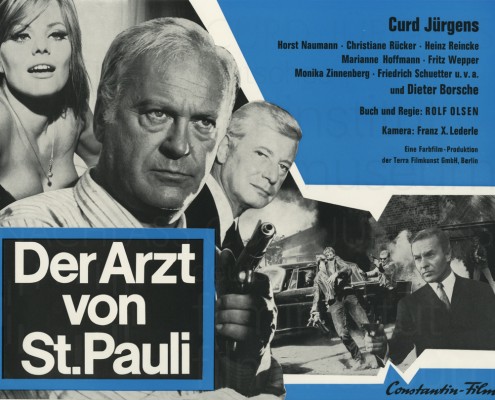

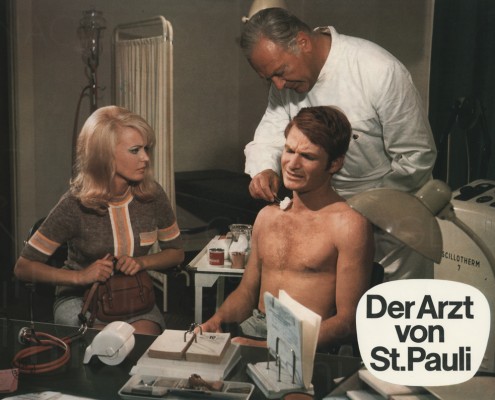

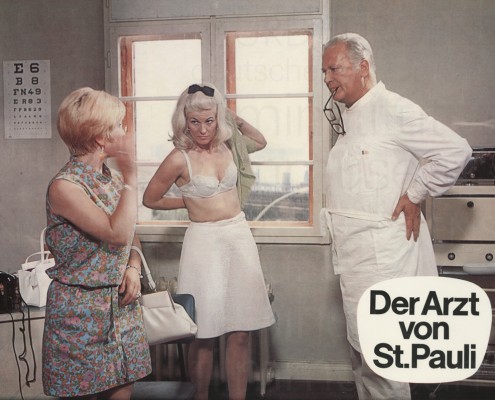

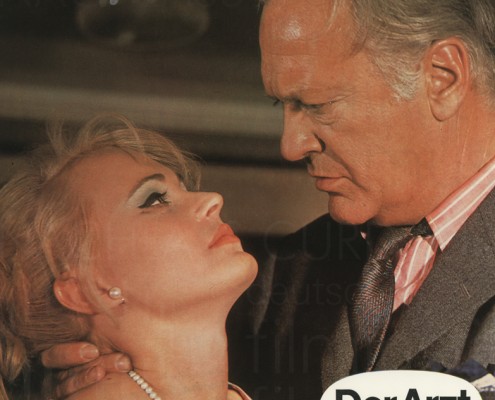

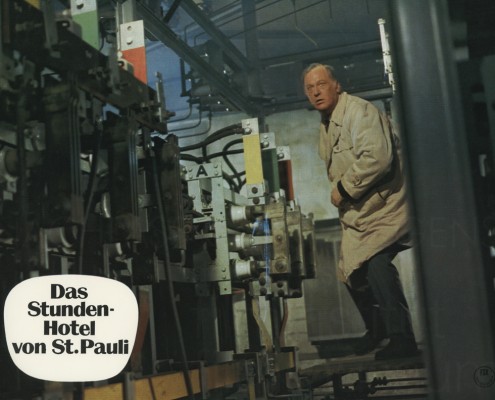

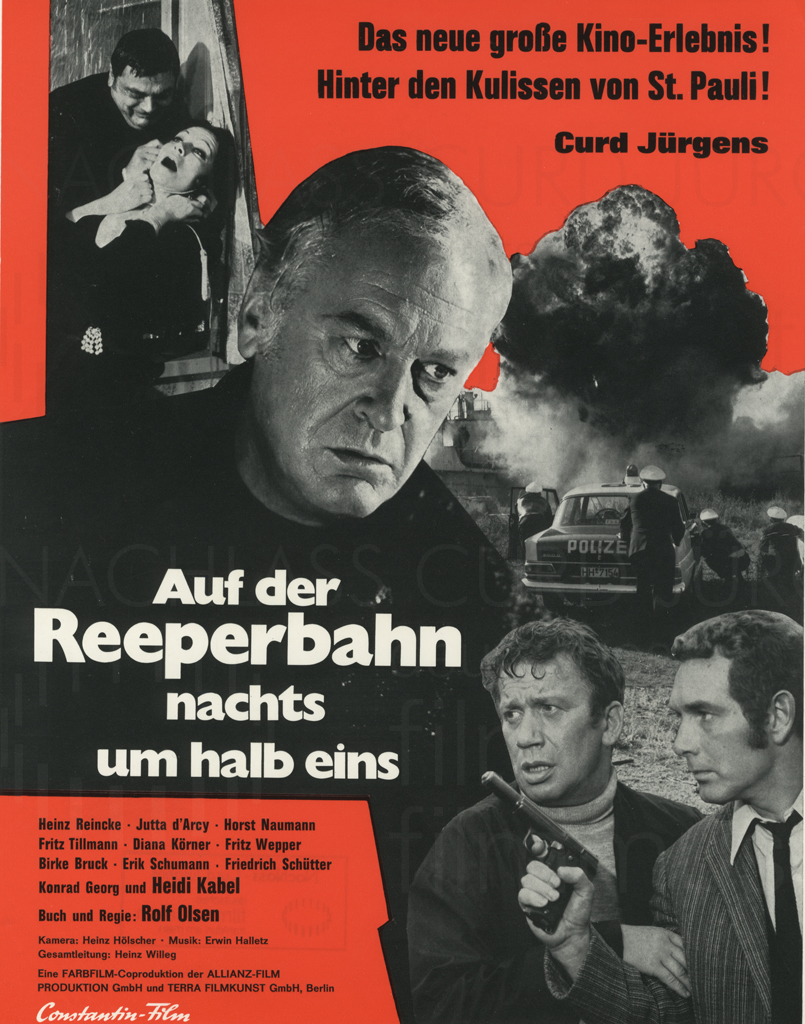

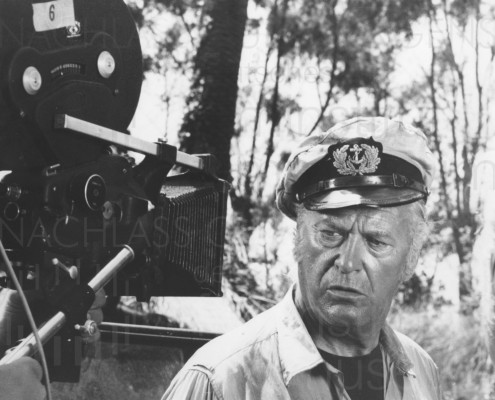

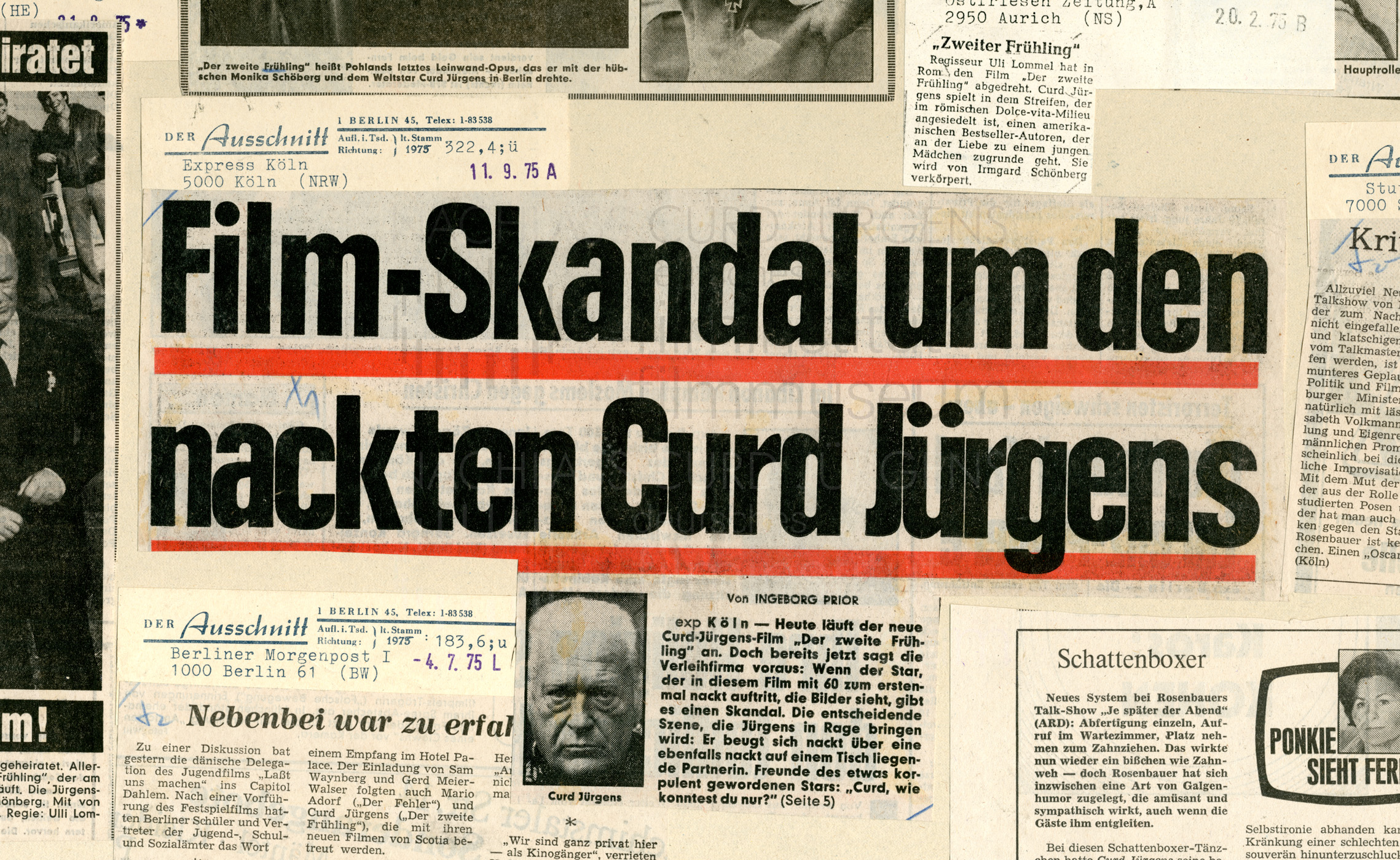

Jürgens was an event, a media phenomenon. Just as he dominated the screen with his physical presence, over 1.92 meters tall and with an expanding waistline, so he filled the gossip columns too. In the 1970s, when flying was still expensive, his lifestyle was called “jet set”, and he claimed on multiple occasions that he had accepted many roles because he had the chance of earning a lot of money. He participated in all of the St. Pauli-Films of the late 1960s and early 1970s, for example, beginning with DER ARZT VON ST. PAULI (The Doctor of St. Pauli, 1968, dir. Rolf Olsen), considered by Jürgens to be genuine popular theatre, because he thought they would make money and because foreign producers scrutinized their box-office results. There were very few bright spots in his later films, and Robert Mitchum’s famous quip “No acting required” applied to most of them. Curd Jürgens was just Curd Jürgens in these films, and his contribution often had the character of a cameo-appearance. In the 1969 film BATTLE OF BRITAIN (dir. Guy Hamilton), a mega production for the period, he is an ambassador of the Third Reich sounding out a special peace with England in Switzerland. Although he is the third name on the credits, his presence on screen is under three minutes and does not amount to any lines more profound than: “We can invade England, whenever we want.”