REMINISCENCES OF ARTUR BRAUNER

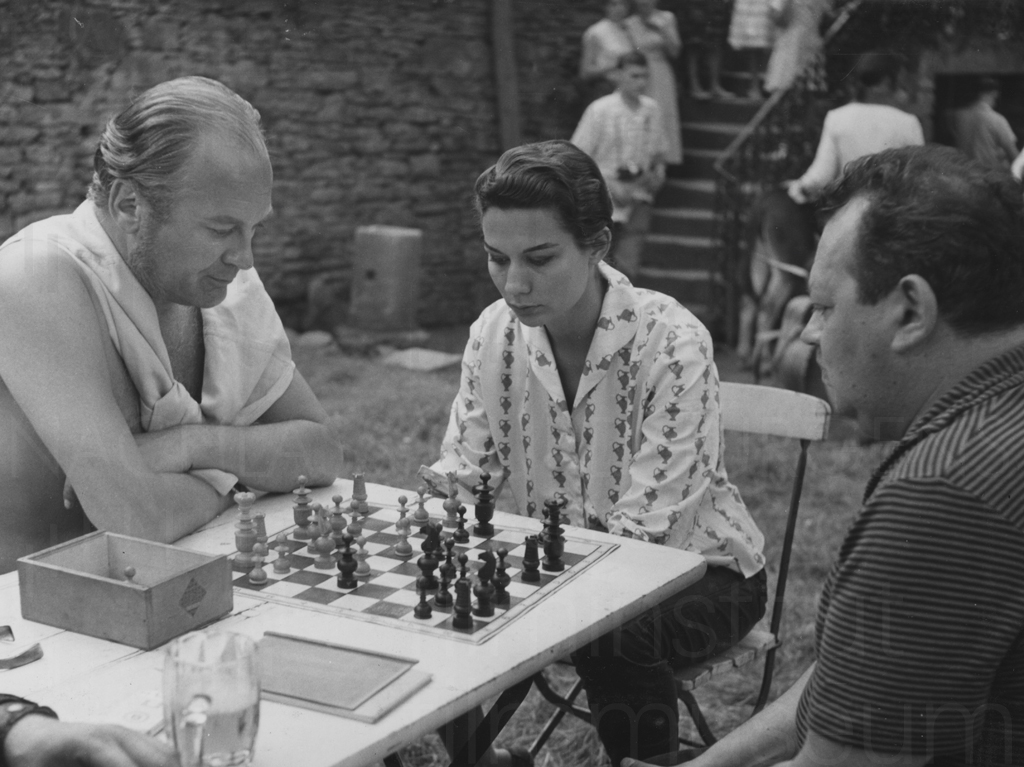

TEUFEL IN SEIDE (1955, D: Rolf Hansen). Look, I’ve just remembered a story. My dear old friend Curd Jürgens starred in this film alongside my equally dear friend Lilli Palmer. Curd was really big business at the end of the 1950s. All of Europe knew him as “the devil’s general”. The Americans idolised him in ME AND THE COLONEL (1958, D: Peter Glenville). In Venice he had been awarded the Coppa Volpi for best acting performance. His films ran in thousands of local small cinemas. And all of them were hugely successful!

So Curd was a big fish, and the producers were throwing out bait to land this fish. A film with Curd Jürgens’ name in the opening credits was foolproof and was as good as ready money. To keep the angling analogy – the German producers’ bait, by which I mean pay, wasn’t tempting enough. Curd counted in six-figure sums and only understood the word “dollars”. And the Hollywood people were much better at enunciating that than the poor Europeans that we were.

Be that as it may, I didn’t give up the race. It is one of the most important qualities of a film producer always to reach for the stars; it is not for nothing that in my production office I have hanging the well-known plaque with the inscription: “We will do the impossible immediately. Miracles take a little longer.”

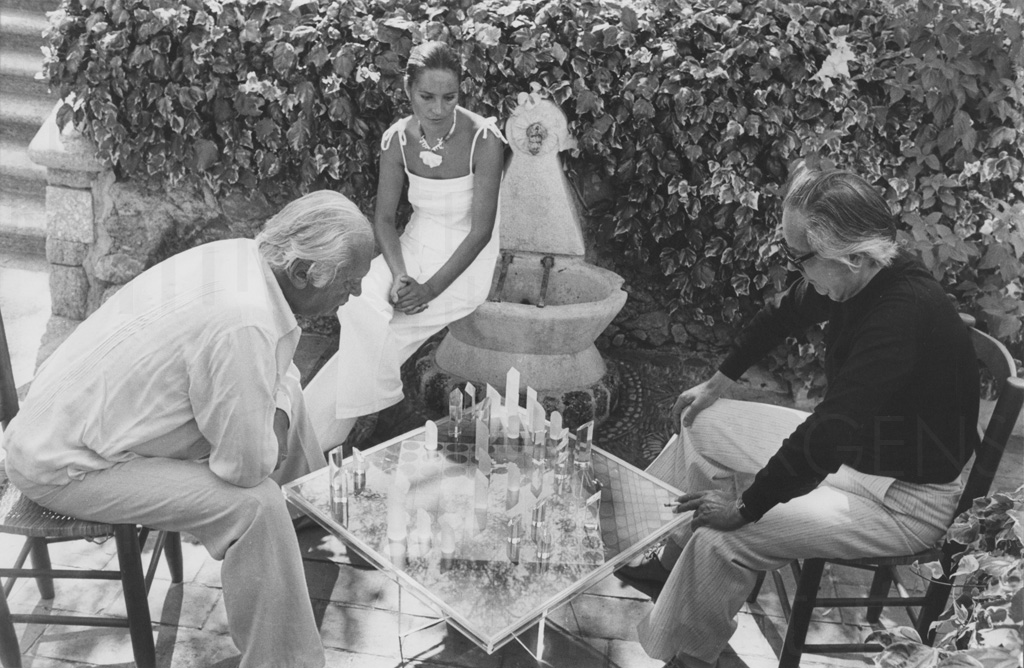

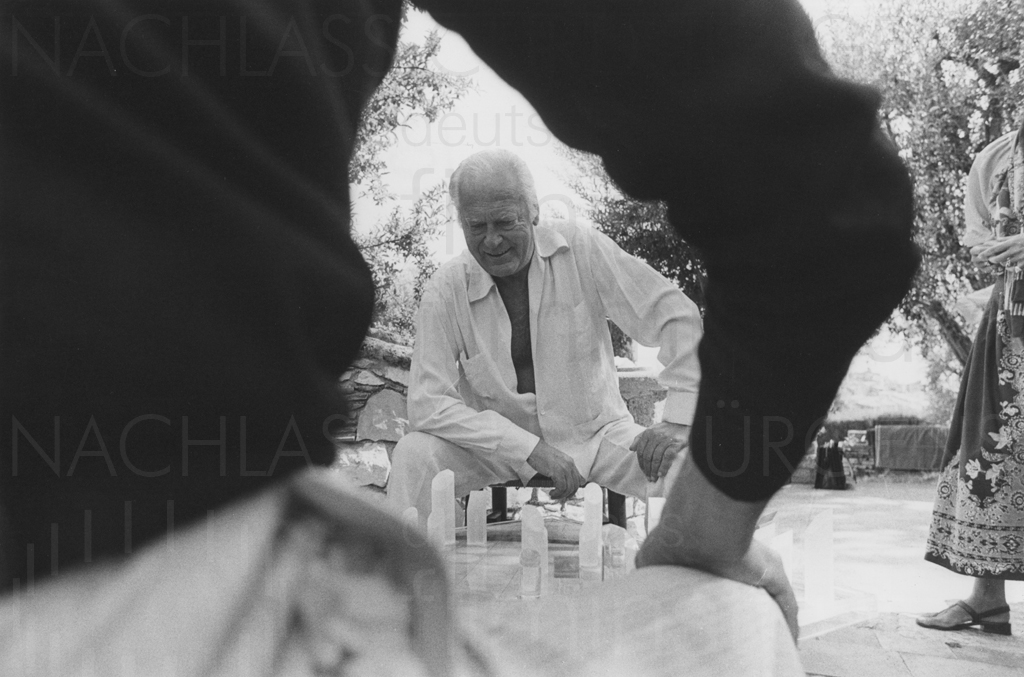

I bombarded Jürgens with ideas for film concepts, draft scenarios, completed scripts, with exciting material, with the most attractive role offers. I telephoned him, called in on him in his fairy-tale castle at Cap Farrat, I wrote him long letters.

His reaction was always the same. “Why should I work for 100,000 when I can work for 500,000? My dear Artur, can you answer me that?” He didn’t wait for me to answer but said: “See – you can’t.” “Does he still not want to do it?” Maria would ask, the best wife in the world, when I had tried once again. “He doesn’t want to,” I would say, slowly and without heart.

“Well, perhaps he will if you suggest Peer Gynt?” Peer Gynt, the seeker after God, the adventurer, the northern Faust, it’s a juicy role for any great actor. Hans Albers had played him in his inimitable manner. But that was nearly 25 years ago and nothing spoke against Curd Jürgens playing him again in his equally inimitable manner. If only he wanted to…

I considered how best to convince him of my idea this time. Then, out of the blue, Sonja Ziemann came to my assistance. “Artur,” she said on the phone, “I do hope you’ll be joining us at my house on the eighth. You will come, won’t you?”