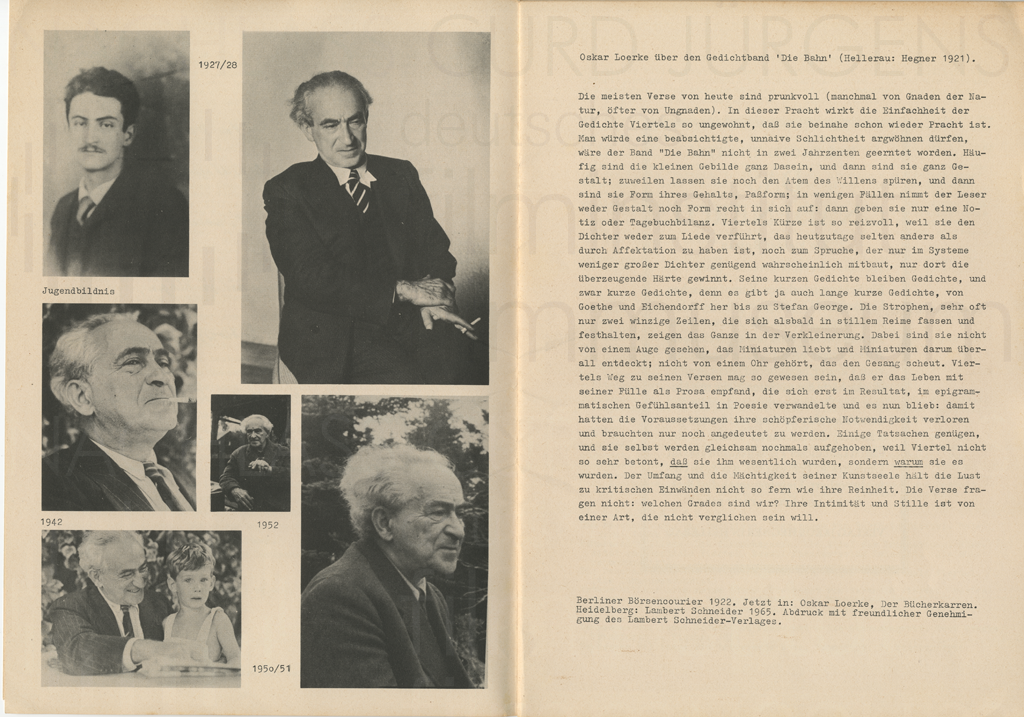

The director Berthold Viertel (28.6.1885–24.9.1953), despite lucrative offers from East and West Germany, had returned to his native Vienna to the Burgtheater where it was not only his production style which fundamentally shaped the theatrical life in Vienna, but also his intensive work with the actors which seemed to be an enriching experience for all concerned. Viertel was, however, also the one who was the first to confront post-war Viennese audiences with plays in which “the people must supply the interest because the proceedings do not, the characters provide fascination because no conflict furnishes us with suspense.“[i] With their repertoire policy, the then director of the Burgtheater Josef Gielen and his brother-in-law and closest associate, Berthold Viertel, consciously took the opposite position to the National Socialist theatre of laughter and improvement where the cultural establishment had the self-imposed task of distracting a population demoralised by many years of waging war and of keeping up their spirits with cheerful romantic comedies and well-tried comedies of mistaken identity.

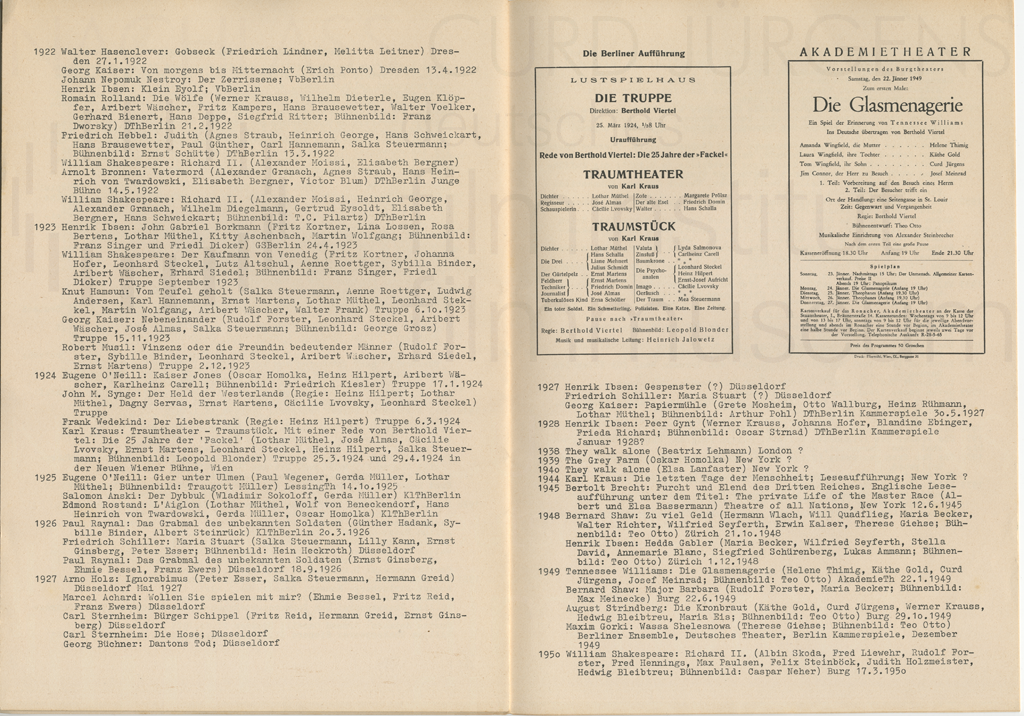

Having Viertel as mentor allowed Jürgens to move away from the commodified drama of the earlier years. The plays selected questioned the causes of interpersonal catastrophes; the psychological wounds inflicted were analysed within the microcosm of the family. The then artistic director at the Burgtheater presented Tennessee Williams’ “psychoanalytical theatre ballads” programmatically to the Viennese public with his own translation and direction. And in a production style that was diametrically different to what had gone on before – what Viertel polemically described as “Reich Chancellery”-style, his term for the outer pathos and “false classicism”[v] of theatre in the Nazi-era. Moreover he cast contrarily. So Curd Jürgens played the character of Tom Wingfield in Tennessee Williams’ “The Glass Menagerie” (1949), a character overburdened by the demands of his family, which was to be followed by a series of challenging psychological roles. Viertel cast the character of the cheerful attractive young man with Josef Meinrad who, until then, had been more successful with comic roles. The critics were taken aback by the unaccustomed role distribution. Jürgens as Tom Wingfield was all at once received as a serious and mature voice actor[vi]: “Then, alongside these two figures (Amanda und Laura Wingfield) from the half-light of poetry there is Curd Jürgens’ Tom, still in the twilight of lower middle class domesticity, and Meinrad’s boyish, uncomplicated everyday healthily optimistic Jim Josef.” Friedrich Schreyvogl – from 1954 himself Assistant Director of the Burgtheater – makes a pointed comment in his review: “It is astonishing how far this young actor’s maturity has come in these last years. He has rich external means at his disposal; we are now conscious of the inner abundance from which he can create.”[viii]

That the director accepted Jürgens into his inner circle despite the actor’s great popularity in the National Socialist era (“Curd and Viertel got on so well that in the end Curd had a part in every play that Viertel produced.”[ix]), may be connected with the fact that Viertel, as a man of the theatre, was primarily interested in the acting resources of his collaborators, as he makes clear in an essay about his collaboration with Werner Krauß.[x] Egon Hilbert too, who was then in charge of administration of the Bundestheater, welcomed Viertel’s casting policy; his unerring view was that Jürgens was undoubtedly one of “the most gifted actors”, “an excellent Theseus” (in Waniek’s setting of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”), whose portrayal of “young, very virile types in modern social comedies” was also quite “wonderful”.[xi] Jürgens could finally lay aside the typecasting as daredevil and charmer.

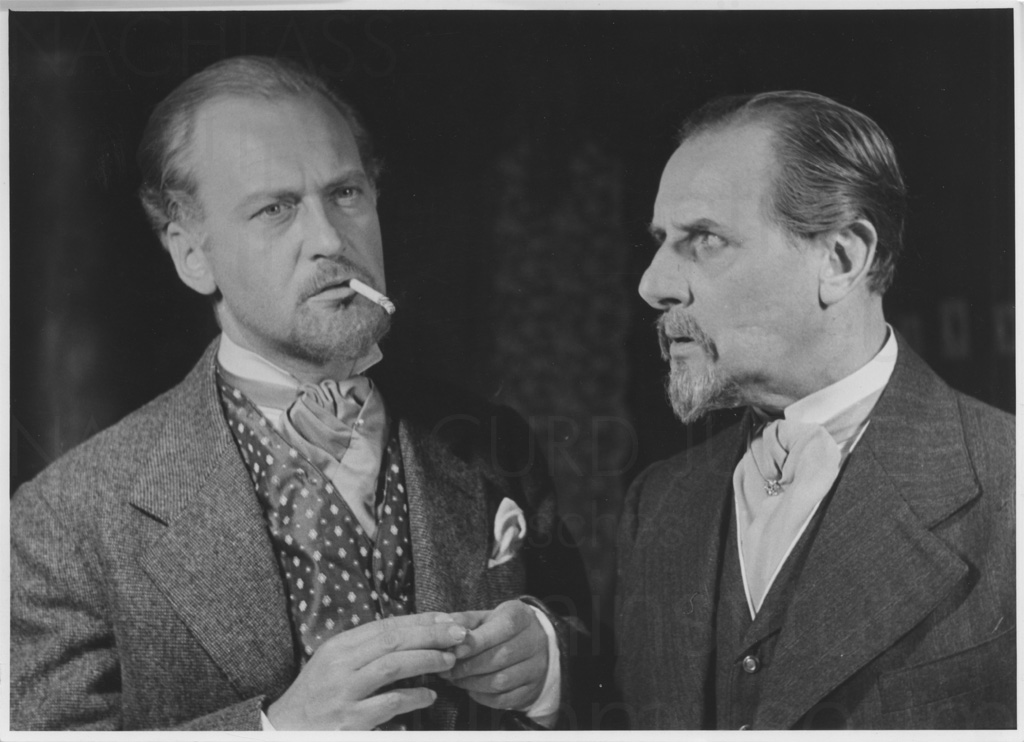

In the role of the unpredictable Trigorin in Chekhov’s “The Seagul”, the actor – a member of the so-called Viertel Troupe – showed himself to be a virtuoso interpreter of character. But Jürgens had successes in supporting roles too, in the world première of “Herbert Engelmann” he was singled out as one of the best supporting actors, and “a sovereign tour de force.”[x]

With Viertel‘s support, Jürgens ventured into directing: in 1952 he produced Schnitzlers’ “Anatol” with Hans Holt in the title role, a production unanimously rejected by the critics. Not only did Jürgens’ sober, unsentimental stage world fail to find favour, he also lacked the director’s craft. A discreet piece of advice went as follows: “The nonetheless not uninteresting experiment[xvi] in staging would have been more effective with Jürgens in the title role.”[xvii]

Despite the stage successes, at the beginning of the 1950s Jürgens moved over completely to screen work. The reason he gave for this was:

“Because the man who inspired me for the theatre, who was my mentor and director – Berthold Viertel – died.”[xviii]

With Berthold Viertel in the background, Jürgens first advanced to becoming that serious and formidable actor that he was subsequently to become in film. When in 1955 his representation of Harras in the film version of “Des Teufels General” made him internationally famous, Jürgens had cast off for good the image from the start of his stage career in “catalytic roles”, that is so say, roles without any significant profile. (The amount of time that is spent on stage is quantitatively not the decisive factor here; the term can be applied even to starring roles.) With the new image of man about town and grand seigneur, which he additionally cultivated in his private life and which he marketed in a media-savvy way, he got on with the business of presenting demanding characters.

Extract from: “Regarding the Theatre Work of a Film Star, or The Question: What would have become of Curd Jürgens if it had not been for Berthold Viertel” by Julia Danielczyk. In: Hans-Peter Reichmann (ed.): Curd Jürgens. Frankfurt am Main 2000/2007 (Kinematograph No. 14).

Translation: Elizabeth Ward

Notes:

[i] Friedrich Schreyvogl: Glasmenagerie. In: Wiener Tageszeitung, 25.1.1949.

[ii] Judith Holzmeister: Curd. In: Margie Jürgens [ed.]: Curd Jürgens. Wie wir ihn sahen. Erinnerungen von Freunden. Vienna, Munich 1985, p. 11.

[iii] Citation from Lilli Palmer: Leading man. In: ibid. P. 42.

[iv] Friedrich Schreyvogl: Endstation Sehnsucht. Rückfall ins Pathologische – Zur Problematik der neuen Tennessee-Williams-Premiere am Akademietheater. In: Wiener Tageszeitung, 22.4.1951.

[v] Berthold Viertel: Verantwortung des Schauspielers. In: Peter Roessler, Konstantin Kaiser: Dramaturgie der Demokratie. Theaterkonzeptionen des österreichischen Exils. Vienna, no year, p. 213.

[vi] N.N.: Großstadtpoesie im Akademietheater. In: Arbeiter Zeitung, 25.1.1949.

[vii] N.N.: Die Glasmenagerie. In: Neues Österreich, 25.1.1949.

[viii] Friedrich Schreyvogl: Glasmenagerie. In: Wiener Tageszeitung, 25.1.1949, no page.

[ix] Judith Holzmeister, loc. cit., p. 13.

[x] See Berthold Viertel, loc. cit., p. 213.

[xi] Letter by Egon Hilbert to the director of Burgtheater, Josef Gielen on 17.3.1948, Austrian Public Record Office, AdR/BmU/BV 460/48. Cit. after: Hilde Haider-Pregler: Das Burgtheater ist eine Idee … In: Hilde Haider-Pregler, Peter Roessler [ed.]: Zeit der Befreiung. Wiener Theater nach 1945. Vienna 1998, p. 101f.

[xii] Edwin Rollett: ,Glasmenagerie’ im Akademietheater. In: Wiener Zeitung, 25.1.1949.

[xiii] N.N.: ,Desire’ – ,Sehnsucht’ oder ,Gier’? In: Die Presse, 28.4.1951.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Friedrich Torberg: Gerhart Hauptmanns ,Herbert Engelmann’. Uraufführung in der Bearbeitung von Carl Zuckmayer in Wien. In: Neue Zeitung, Munich, 10.3.1952.

[xvi] N.N.: ,Anatol’ im Akademietheater. In: Die Presse, 15.6.1952.

[xvii] See Edwin Rollett: ,Anatol’ im Akademietheater. In: Wiener Zeitung, 15.6.1952.

[xviii] Interview with Curd Jürgens in blick, 1960, newspaper article, Österreichisches Theatermuseum, no page.