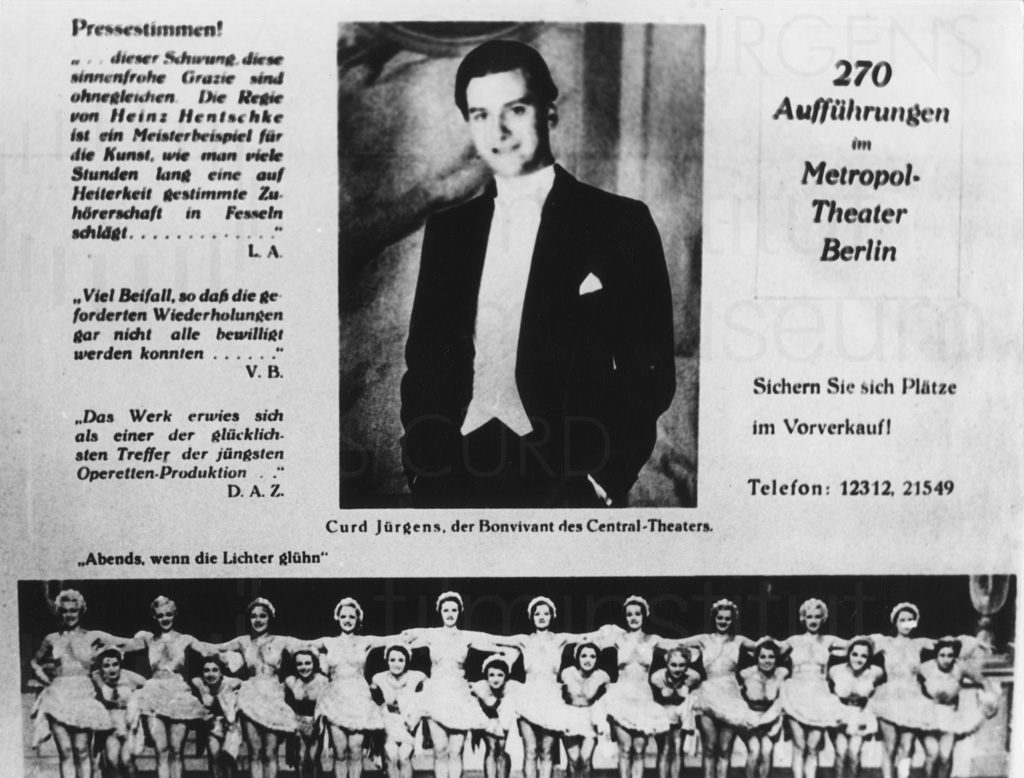

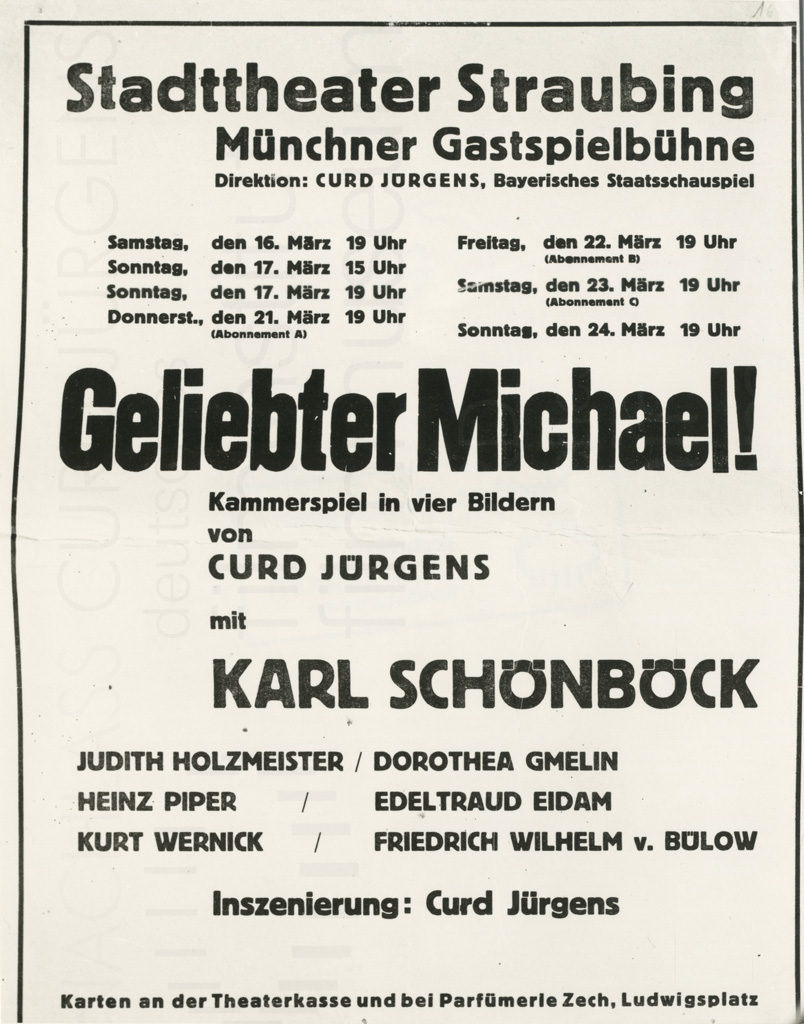

Jürgens began his theatrical career as a singing bonvivant in “Ball der Nationen” in the Central-Theater Dresden, which was a branch of the Berlin Metropol-Theater. He appeared in Berlin at the Theater and Komödie am Kurfürstendamm in so-called conversation pieces. In 1937, on the advice of his theatrical colleague Lizzi Waldmüller, Curd Jürgens applied for a position with the director Rolf Jahn at the – as it was then – Deutsches Volkstheater in Vienna, but at least initially no contract followed.

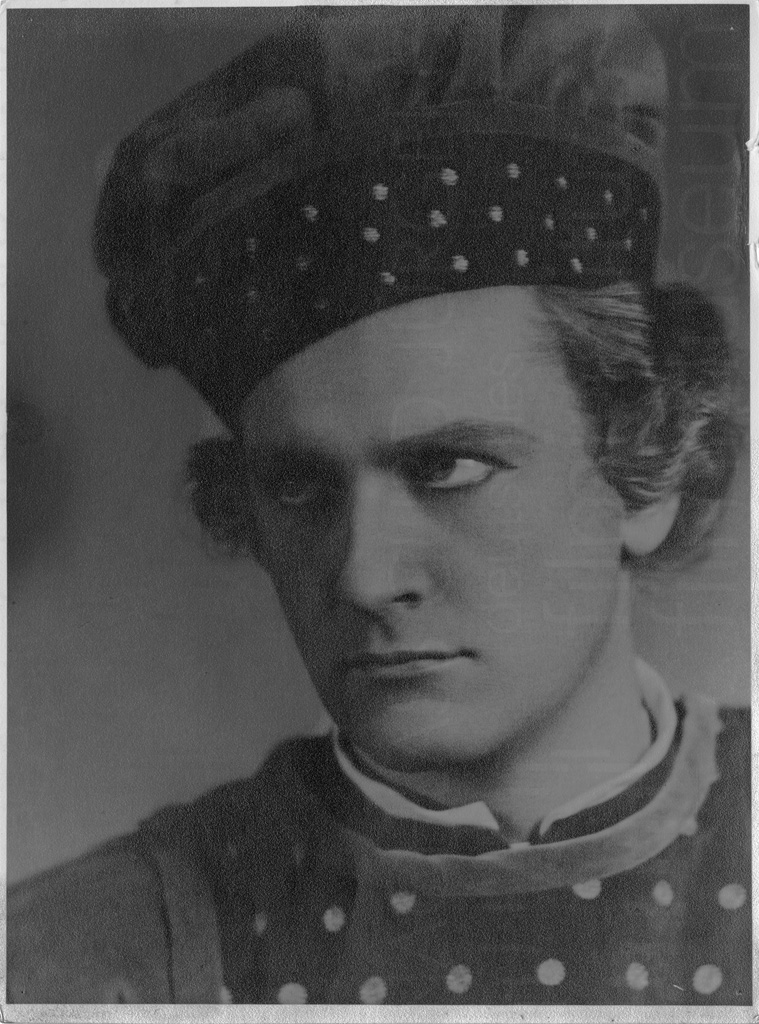

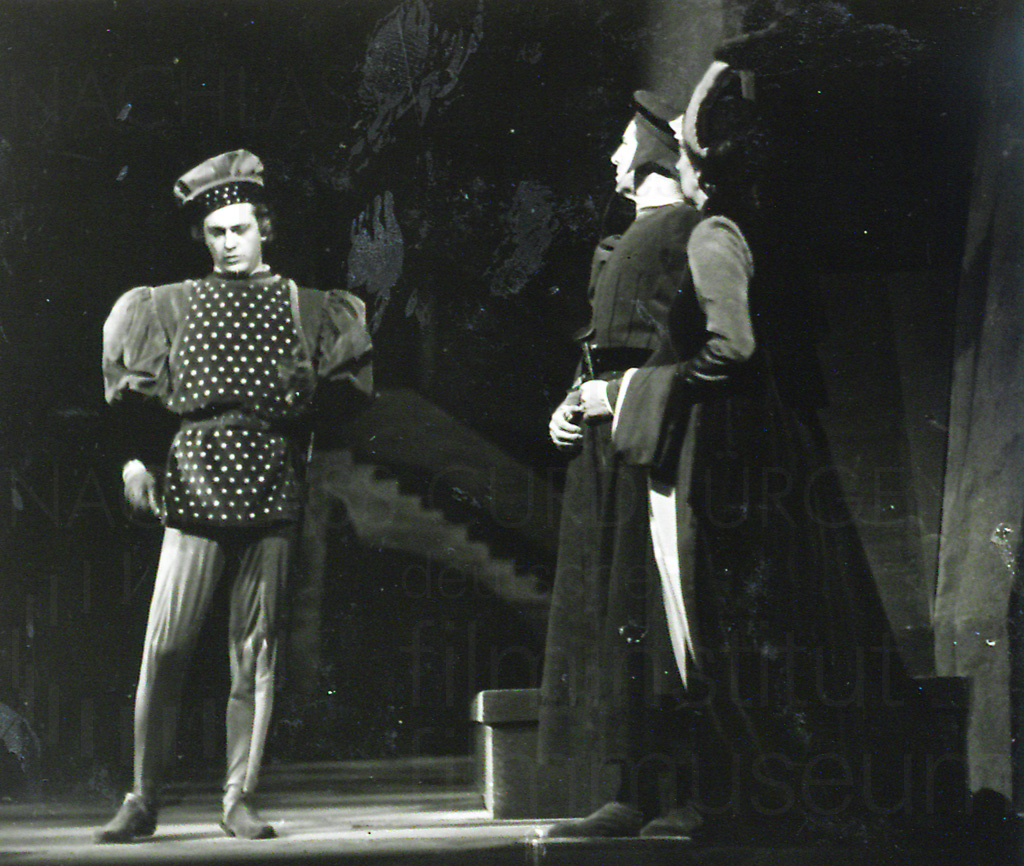

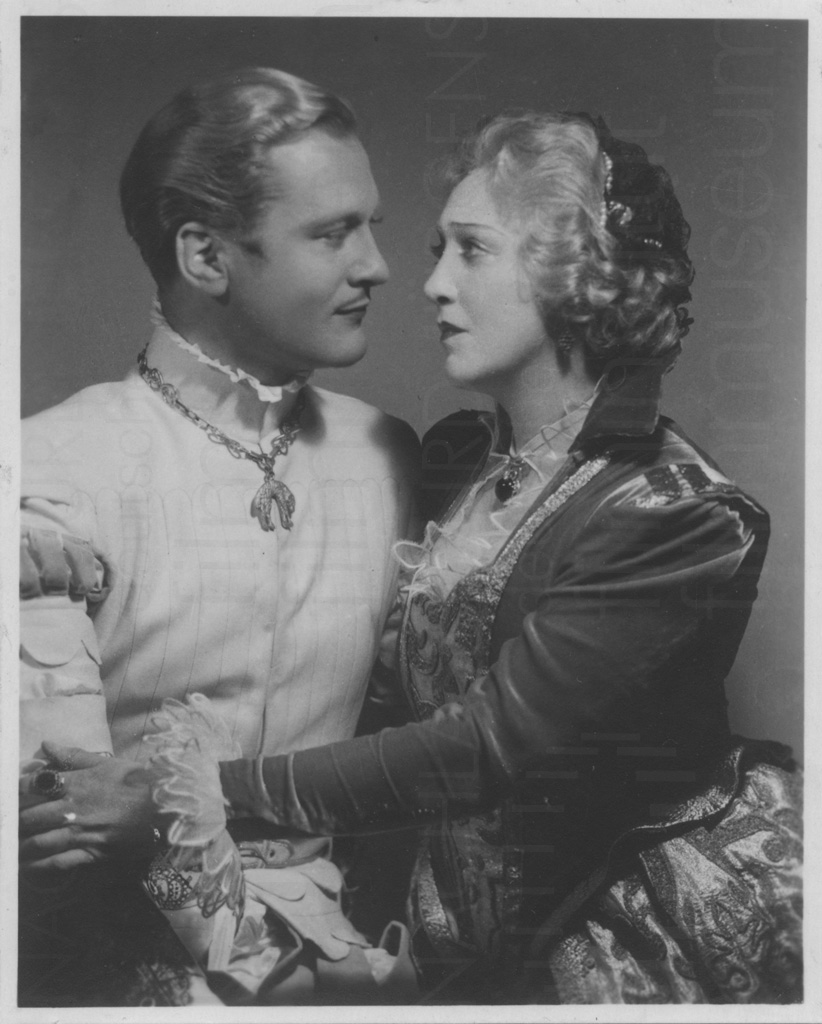

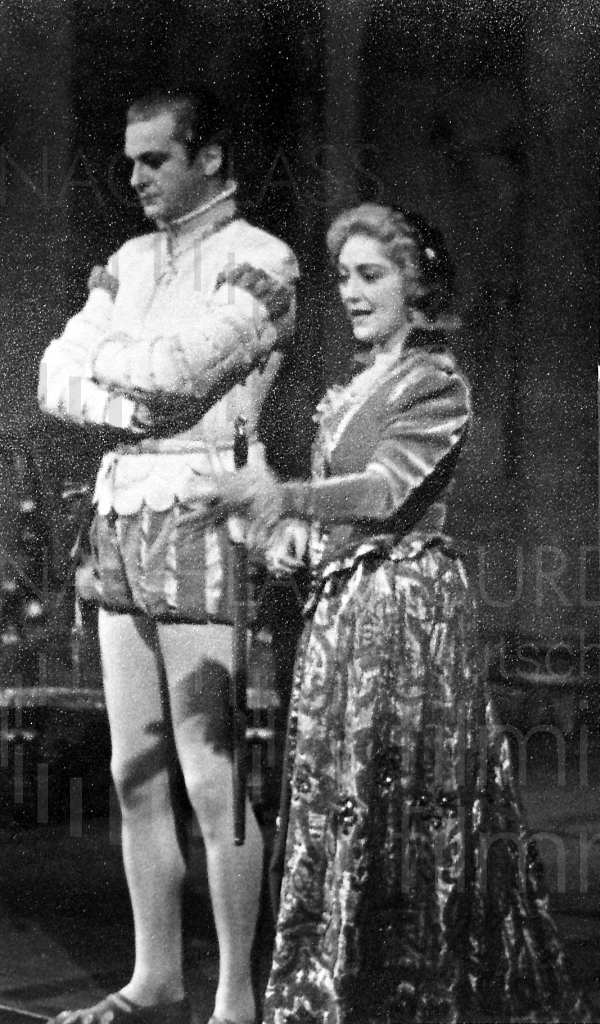

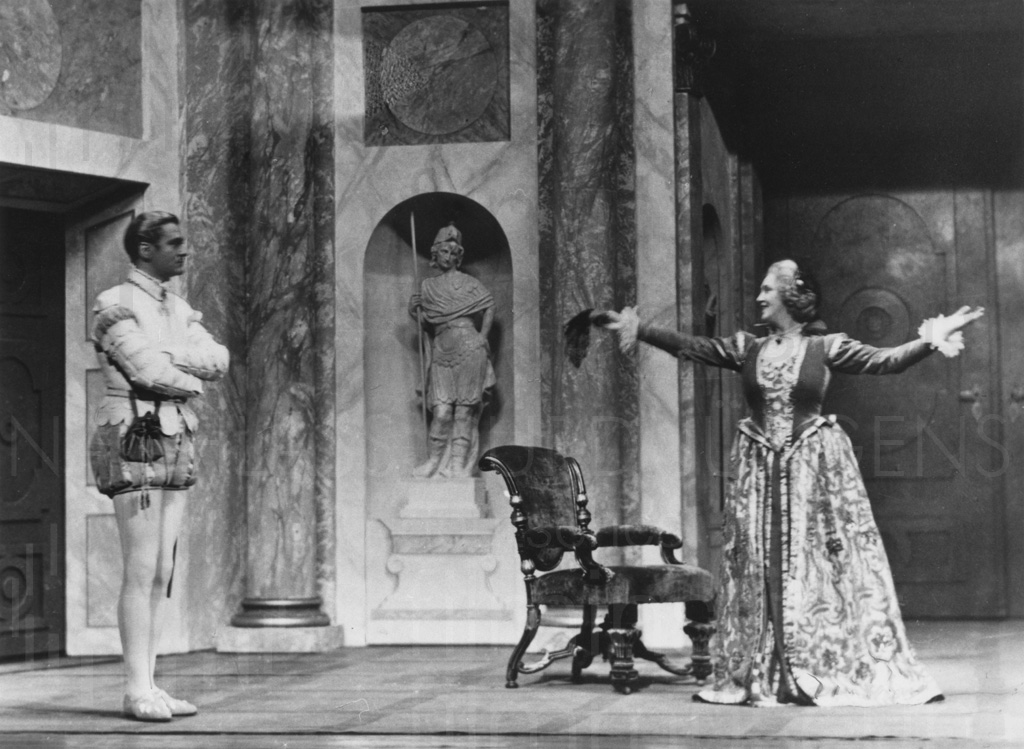

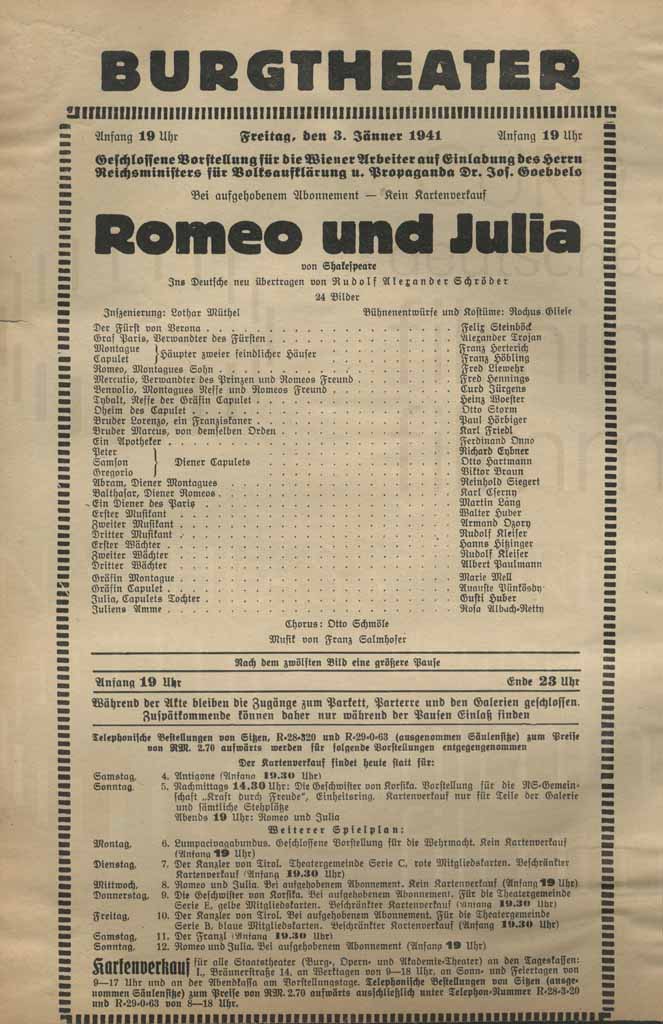

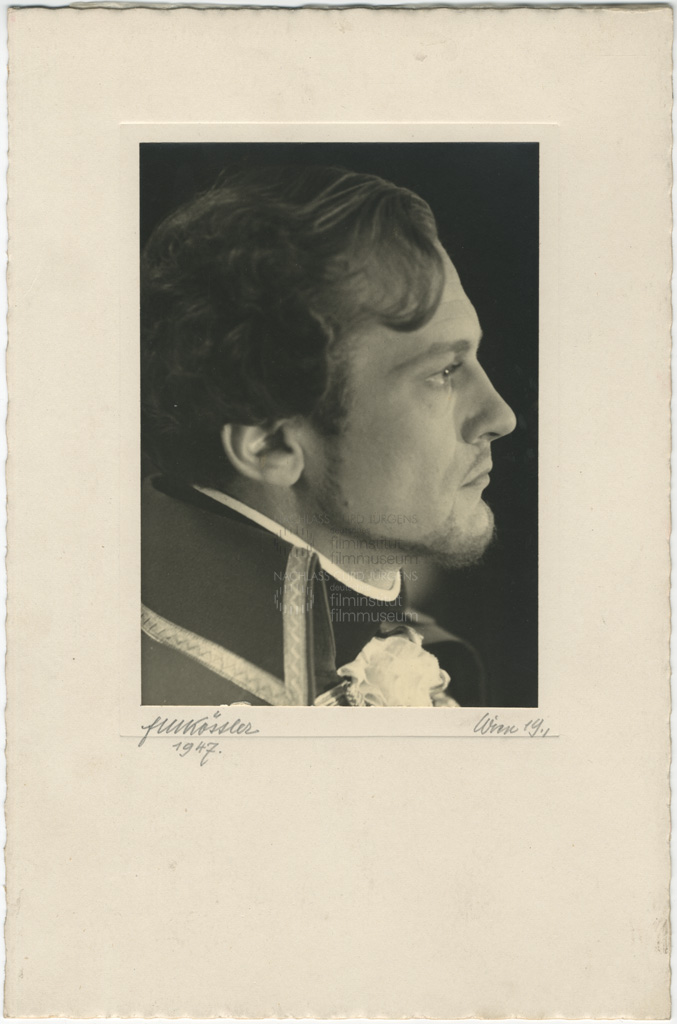

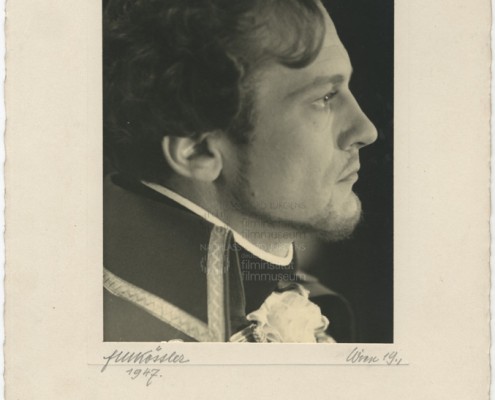

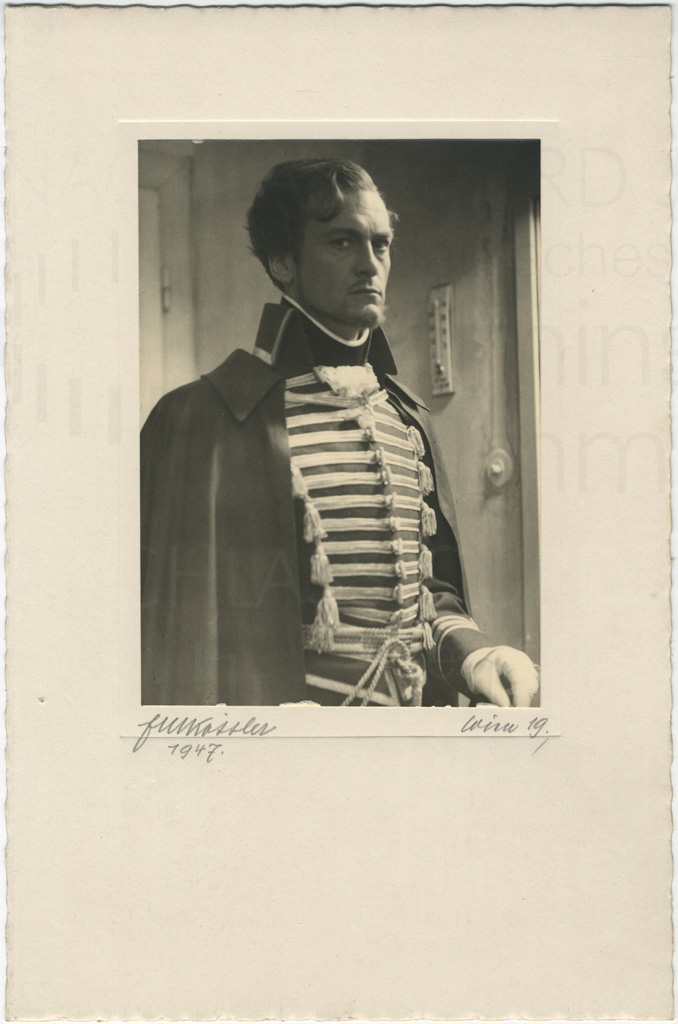

With the charisma of the “sun-bright, blond, youthful daredevil”[ii] alongside Gusti Huber who, like Jürgens, would later find success in the cinema, the actor, unknown in Vienna, was received with enthusiasm. With critical distance Jürgens himself comments many years later:

“I am probably praised primarily because the new blond German matches what the Viennese in their enthusiasm for the “Anschluss” want to see – and hear.”[iii]

And:

“I felt like an intruder because I had come little by little to the conviction that, but for Hitler’s invasion, I would never have come here, would never have been engaged.”[iv]

Extract from “Regarding the Theatre Work of a Film star, or The Question: what would have become of Curd Jürgens if it had not been for Berthold Viertel” by Julia Danielczyk.

In: Hans-Peter Reichmann (ed.): Curd Jürgens. Frankfurt am Main 2000/2007 (Kinematograph No. 14)

Translation: Elizabeth Ward

Notes:

[i] Austrian Public Record Office, AVA, BmU, Gz 15, Business number: 16921, 1937.

[ii] N.N.: Deutsches Volkstheater. Komödie ,Ein ganzer Kerl’. Newspaper article of the Curd Jürgens’ inheritance, Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt am Main, no place, May 1938.

[iii] Curd Jürgens: … und kein bißchen weise. Locarno 1976, p. 179f.

[iv] Ibid., p. 180.

[v] Herbert Mühlbauer: Ein ganzer Kerl. Newspaper article of the Curd Jürgens’ inheritance, Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt am Main, no place, May 1938.

[vi] N.N.: Volkstheater-Premiere: Buch: ,Ein ganzer Kerl’. In: Neue Freie Presse, 5.5.1938.

[vii] Adelbert Muhr: Deutsches Volkstheater. ,Ein ganzer Kerl’ von Fritz Peter Buch. In: Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 5.5.1938.

[viii] Curd Jürgens: … und kein bißchen weise, loc. cit., p. 223.

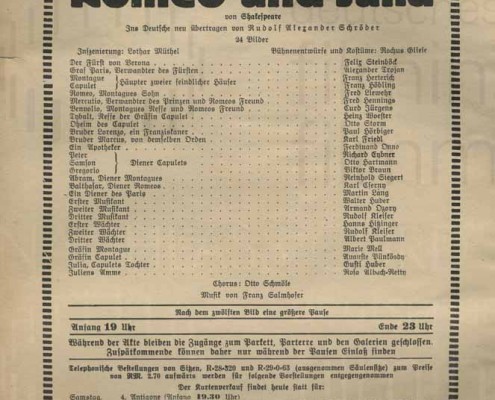

[ix] Mirko Jelusich: ,Romeo und Julia’ in der Burg. Newspaper article of the Curd Jürgens’ inheritance, Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt am Main, no place and year.

[x] Joseph Handl: Hauptmann-Erstaufführung des Burgtheater. Newspaper article of the Curd Jürgens’ inheritance, Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt am Main, no place, March 1943.

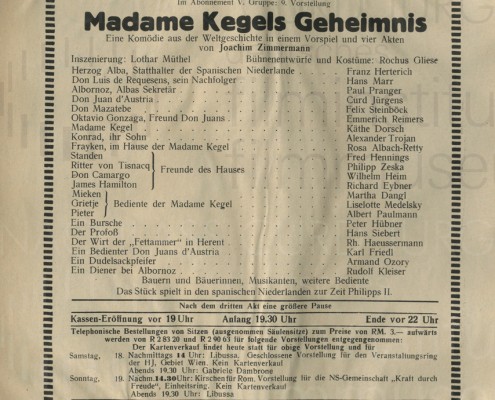

[xi] Bruno Prohaska: Burgtheater: ,Madame Kegels Geheimnis’ von Joachim Zimmermann. Newspaper article of the Curd Jürgens’ inheritance, Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt am Main, no place and year.

[xii] Zeno von Liebel: Ein Vater ,entdeckt’ seine Söhne. Italienische Komödie im Akademietheater. In: Wiener Mittag. Newspaper article of the Curd Jürgens’ inheritance, Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt am Main, no place and year.

[xiii] Felix Fischer: ,Genoveva’ im Burgtheater. In: Wiener Mittag, 4.6.1942, newspaper article of the Curd Jürgens’ inheritance, Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt am Main.

[xiv] Otto F. Beer: Theater, Romantik und Witz. ,Der Lügner und die Nonne’ im Akademietheater. In: Wiener Mittag, 19.6.1942, newspaper article of the Curd Jürgens’ inheritance, Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt am Main.

[xv] N.N.: ,Stella’. Gastspiel des Wiener Burgtheaters. Zürcher Theaterwochen. In: Die Tat, 21.6.1947, newspaper article of the Curd Jürgens’ inheritance, Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt am Main.

[xvi] Herbert Mühlbauer: ,Stella’ im Akademietheater. In: Wiener Kurier, 23.5.1947.

[xvii] N.N.: Curd Jürgens spielt Operette. No Place, 1943, newspaper article, Österreichisches Theatermuseum.

[xviii] Zeno von Liebl: ,Titania’ im Akademietheater. In: Neues Wiener Tagblatt, 19.2.1944.

[xix] Rudolf Holzer: Die Frau des Potiphar. In: Die Presse, 9.8.1947.