REMINISCENCES OF SENTA BERGER

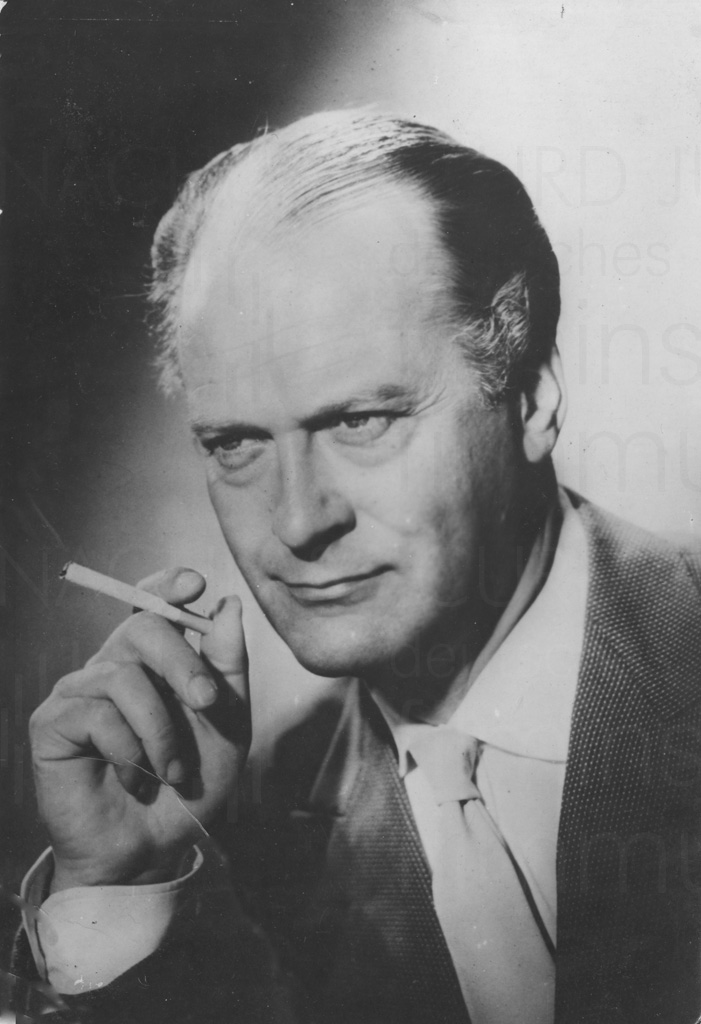

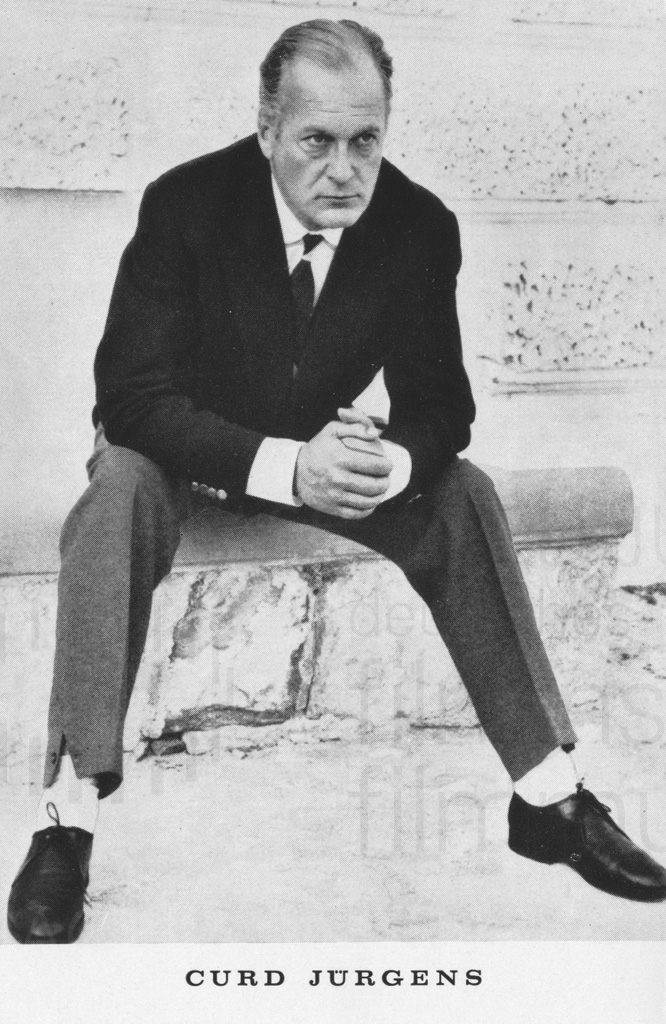

I was eight years old and had fallen head over heels in love with Curd Jürgens.

In our little cinema in the suburbs of Lainz on the outskirts of Vienna, he had smiled at me and his blue eyes sparkling. The film was WIENER MÄDELN (1949, D: Willi Forst). I was seated on my mother’s lap for half-price entry and couldn’t imagine that Curd Jürgens could have been smiling at my mother or any another woman in the darkened room or even his partner in the film.

No – the smile was meant for me and it struck me in the heart.

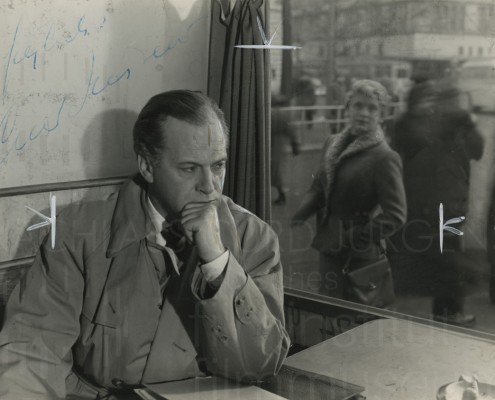

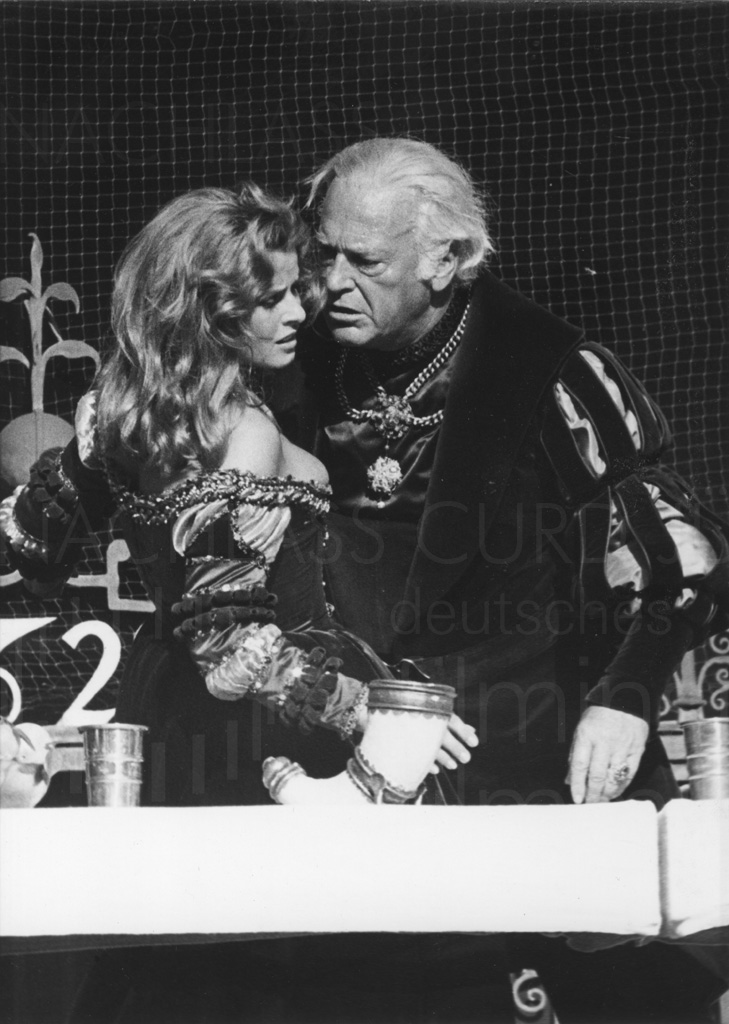

It was easy to fall in love with Curd Jürgens. He was what they would call in Vienna “a snazzy guy”, manly, a counterpart to most film actors in the 1950s. There was something urbane about him – I couldn’t put my finger on it at the time – and the word “self-irony” wasn’t yet familiar to me. Curd had a lot of that. But what I saw and what I felt was the allure of a man who was obviously free, who was unashamedly aware of his erotic power and who enjoyed life – with no regrets and with no concessions to the double morality of the 1950s.

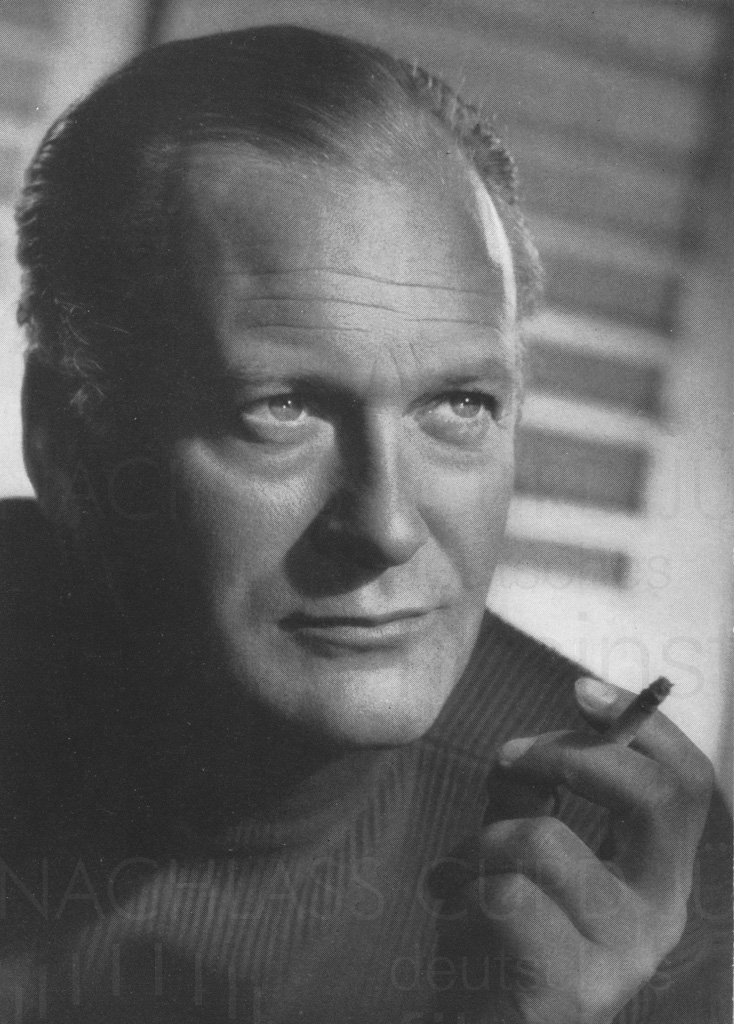

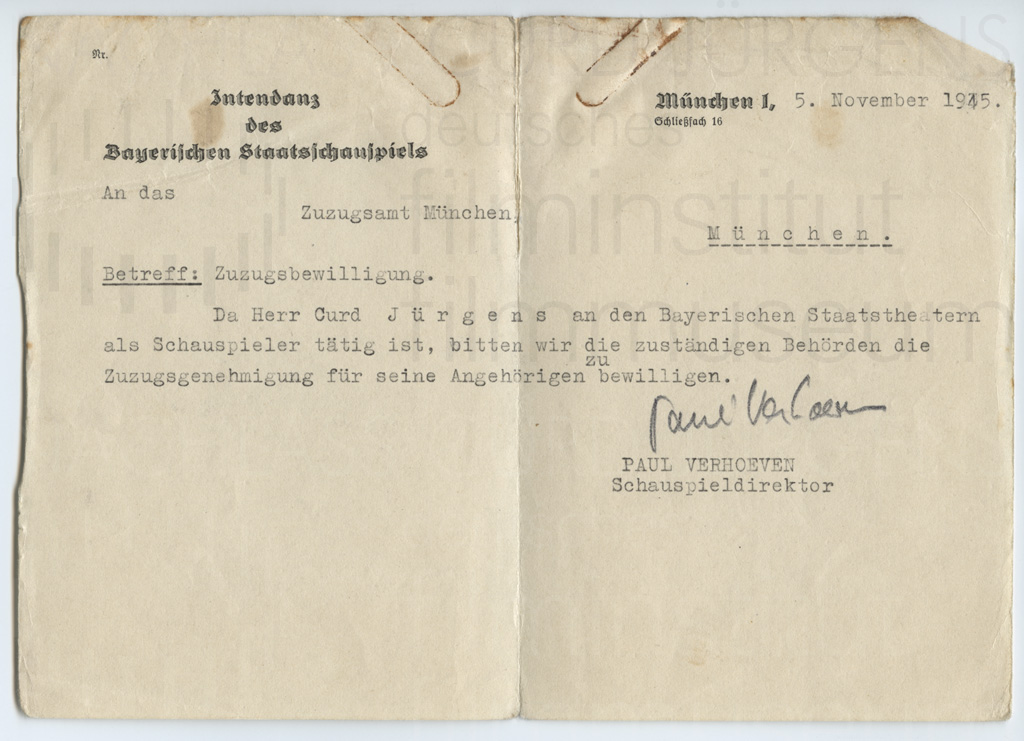

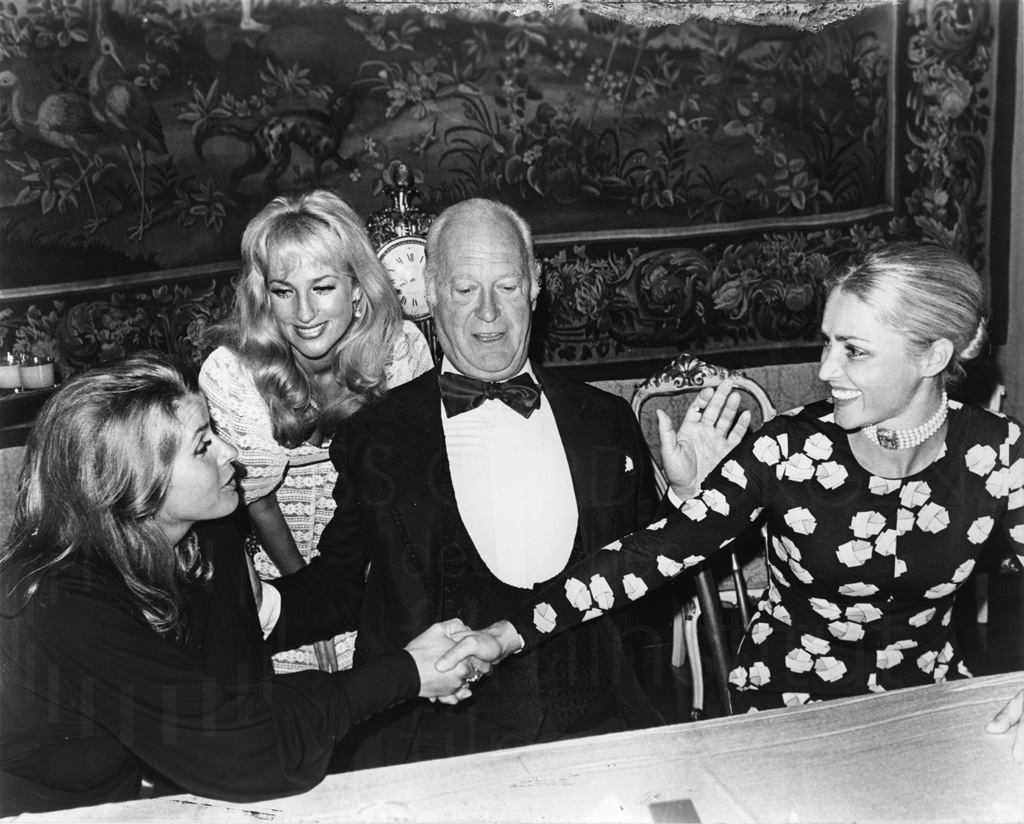

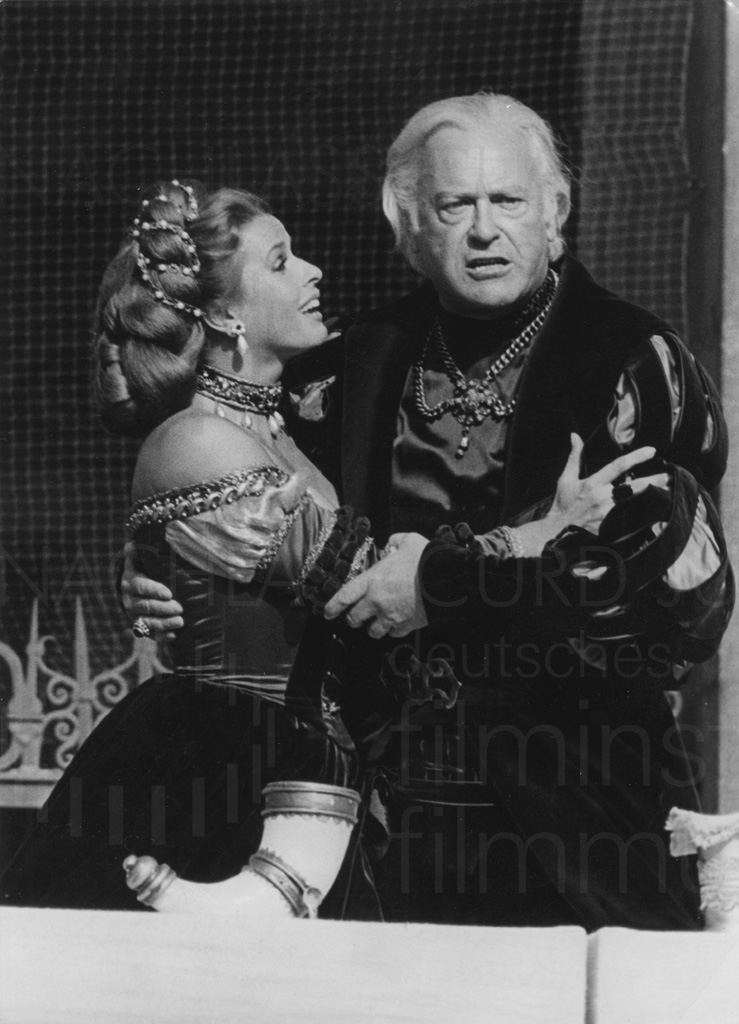

I grew older and fell in love with Karli Rauschmeier, the caretaker’s son. We would sit on the carpet pole and hold hands. I thought of Curd Jürgens leaning over Luise Ullrich and kissing her. His lips were pressed to hers, his nostrils quivered and Luise trembled when Curd let her go, and all but pushed her away in overpowering passion. That was in the film EINE FRAU VON HEUTE (1954), by the director Paul Verhoeven. Later he was to become my father-in-law. But I didn’t know that yet.

Curd Jürgens played the most beautiful of roles in my young girl’s dreams for a long time. I had a burning interest in everything about him, even his wives, who were all extraordinarily pretty but not always right for him, as I thought, and when he left them or they left him I’d say I’d known that that would happen all along and why hadn’t he asked me for my advice?

A few years later, Curd Jürgens began to work abroad and it seemed like he had always been part of the international film scene. Although he was so German, much more German than people in America and France thought.

Curd loved the German language and especially the soft variant spoken in Austria. He loved both these countries and their culture, their literature, music and theatre, to which he stressed he owed so much, and which remained a benchmark for him for all of his life.

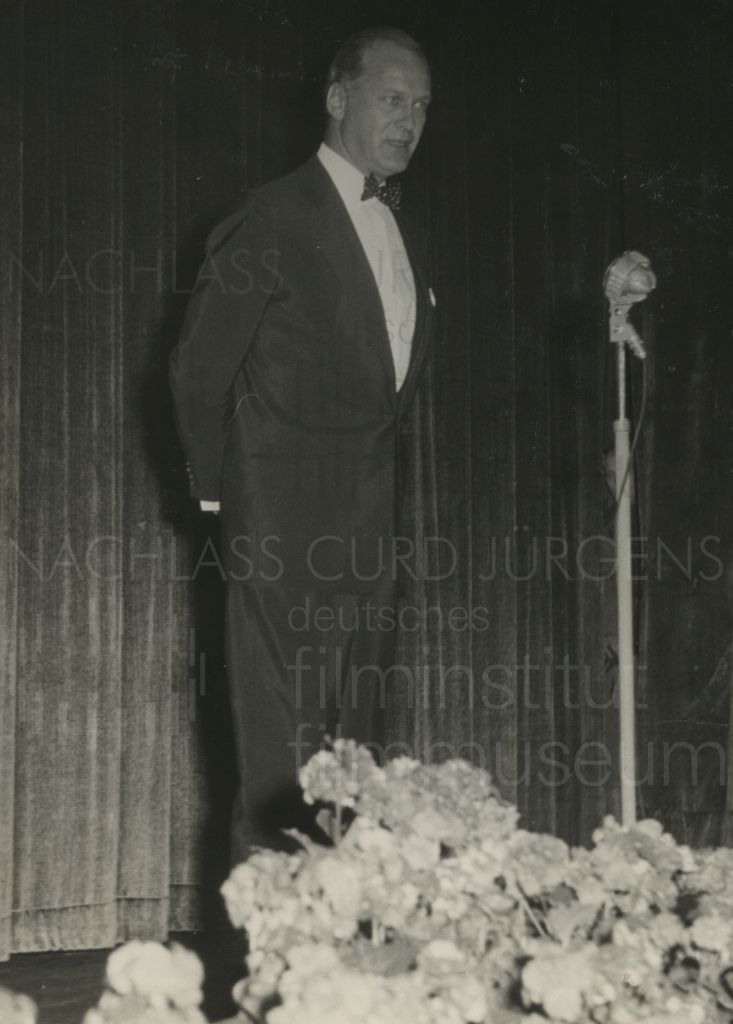

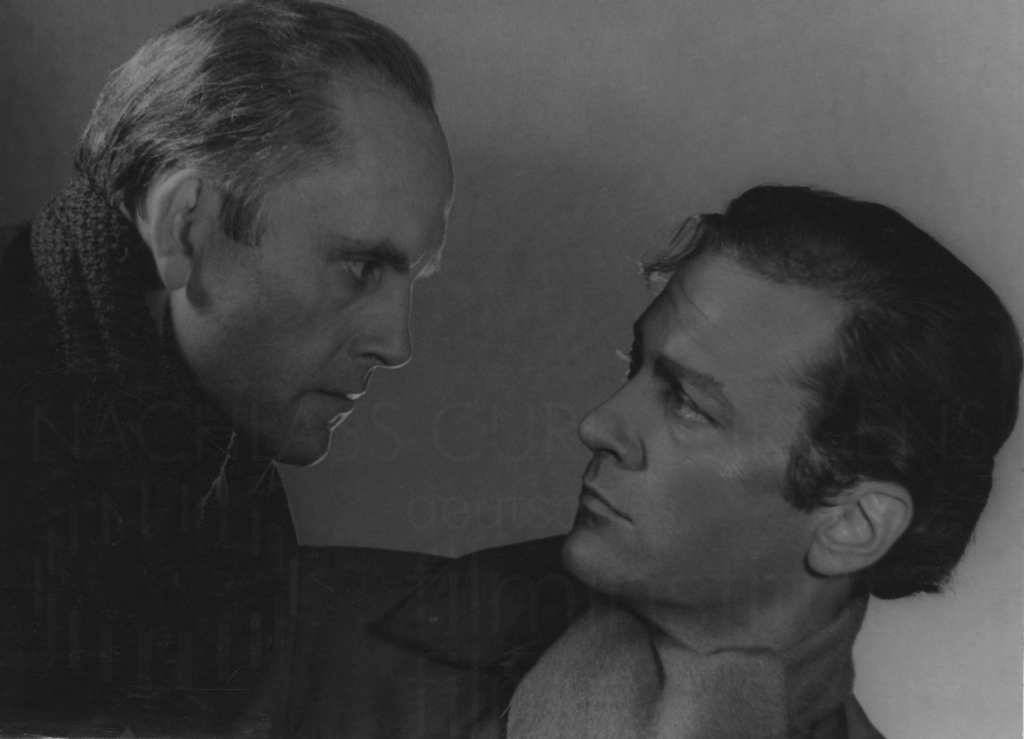

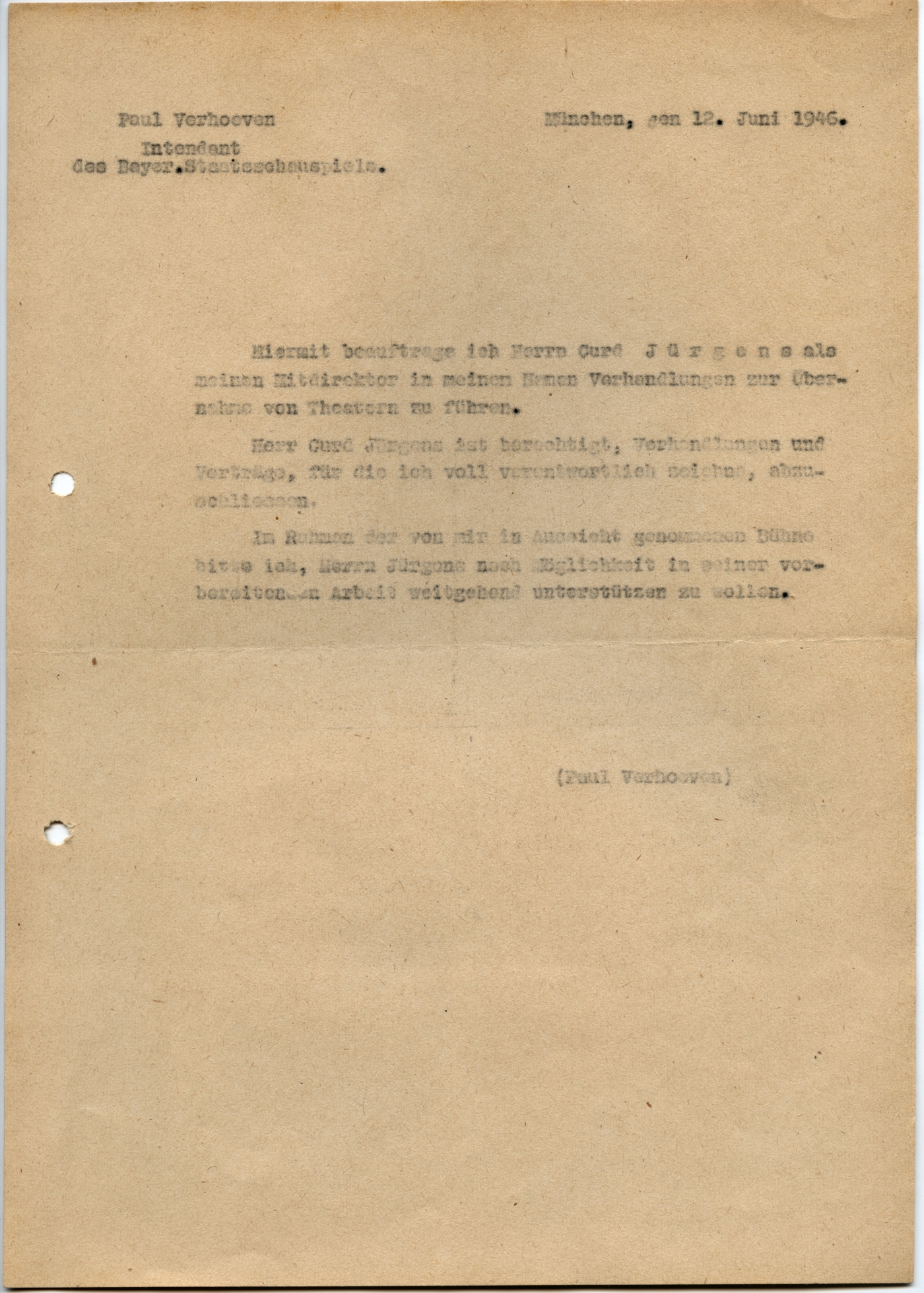

I was studying at drama school. I now looked at Curd Jürgens critically, severely, with the demands due to someone one admires. I had seen him as Bruno in DIE RATTEN (1955), a mangy loser and unforgettable; of course, in DES TEUFELS GENERAL (The Devil’s General, 1954, D: Helmut Käutner) – a film unthinkable without him – and as a pimp in PRATERHERZEN (1953), a film by Paul Verhoeven. Paul had summoned Curd Jürgens to his theatre, the Brunnentheater in Munich, immediately after the end of the war to do some productions. Paul was both a director and an actor.