In TANGO NOTTURNO (1937, D: Fritz Kirchhoff), a film often overlooked by early film historians, his input as an actor in just two scenes barely goes beyond that of an extra. The film starred Albrecht Schoenhals und Pola Negri.

Not much more can be said about his contribution in the film DAS MÄDCHEN VON GESTERN NACHT (1938, D: Peter Paul Brauer) in which he plays the part of an attaché in the British Foreign Office without any traits of note beyond his screen persona. Nonetheless, he earned 1200 Reichsmarks for his role. Irrespective of this, the making of this buoyant film with its witty dialogue, and the accomplished and charming star performers of both sexes must have been an instructional delight for the others in the studio. The Berlin première was on 14 April 1938 in the Gloria-Palast, but except for one group photograph taken from a film magazine of the time, in which a truncated Curd Jürgens can be made out, there are no further documents to be found.[i]

In the Zarah Leander film ZU NEUEN UFERN (D: Detlef Sierck), which premièred in August 1937 also at the Ufa-Palast am Zoo, Curd Jürgens was entrusted with the small speaking role of a dandy in London society at around the middle of the nineteenth century. If in general he is not particularly forthcoming in his reminiscences about the films he made up to the end of the war, here he makes an exception. He is upfront in his admission that he repeatedly messed up the dance scene with the chanson-singer Gloria Vane, acted and sung by Zarah Leander. He misunderstood the pacing and delivery in the love scenes and it led to Leander making an unflattering comment about him in the presence of the recording crew. Strangely enough, it is now impossible to find this scene in the film. It must have disappeared, and certainly not by accident, on the cutting-room floor.

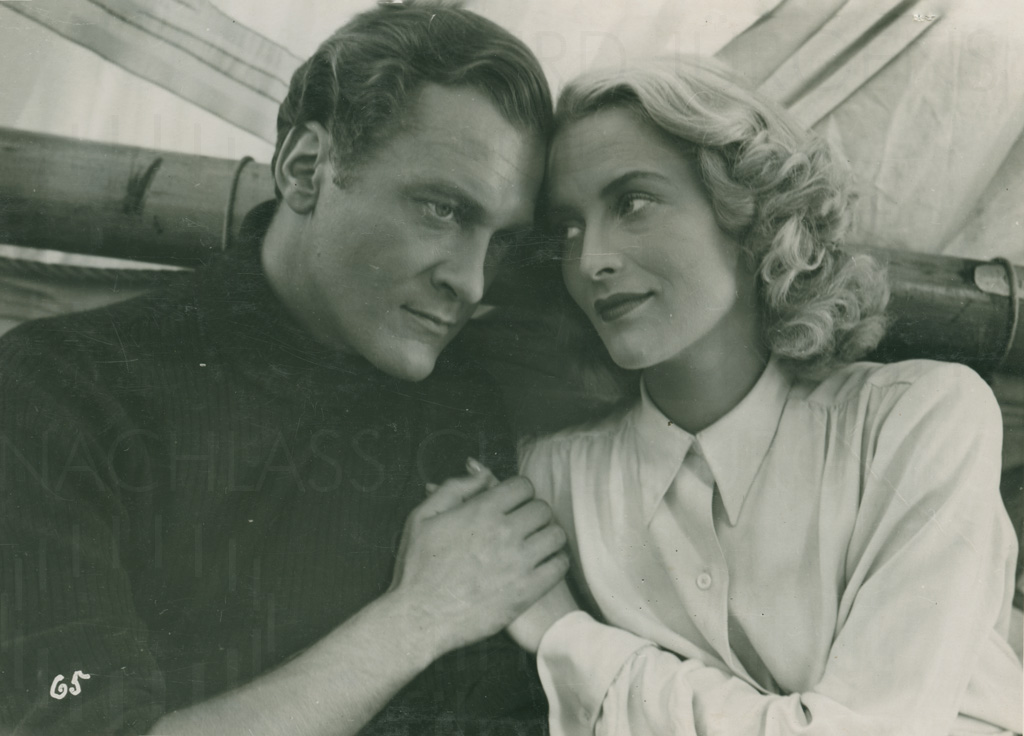

With Maria Niklisch in SALONWAGEN E 417 (1939; D: P. Verhoeven)

With Maria Niklisch in SALONWAGEN E 417 (1939; D: P. Verhoeven)

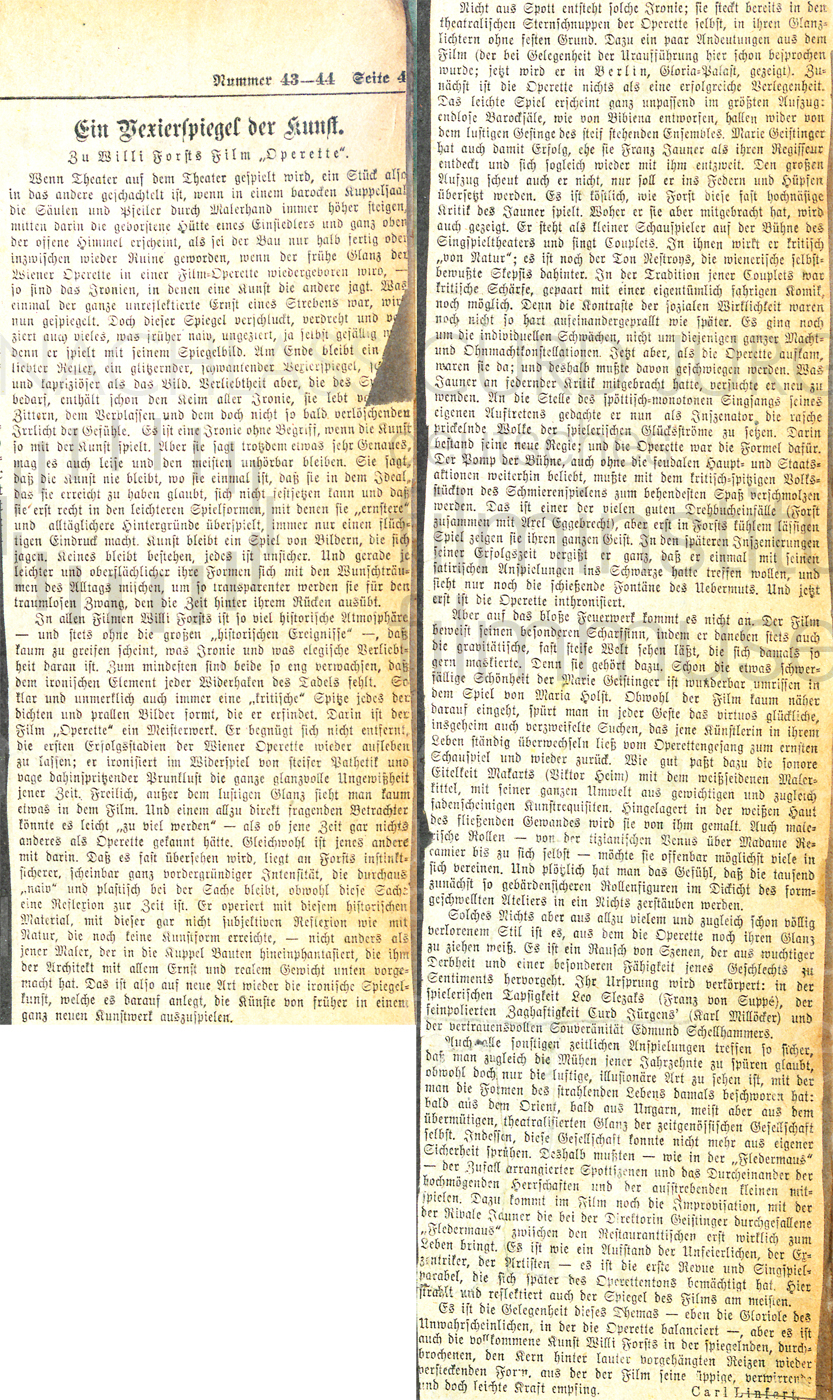

Reviews to SALONWAGEN E 417 (1939)

Although not mentioned either in the programmes or the opening credits, STIMME DES HERZENS (1942) is Ernst von Wildenbruch’s much-read short story “Francesca da Rimini” from 1901 brought to the stage and transposed to a time set between about 1906 and 1910. The story is set in an unnamed Hanseatic town. This role gave Curd Jürgens, who is hardly noted in the casting lists, a greater opportunity to be in the studio with notable fellow actors like Marianne Hoppe, Carl Kuhlmann and Eugen Klöpfer and work under the sensitive direction of Johannes Meyers. The world première took place in the Capitol am Zoo in October 1942 with the film running for 23 days.

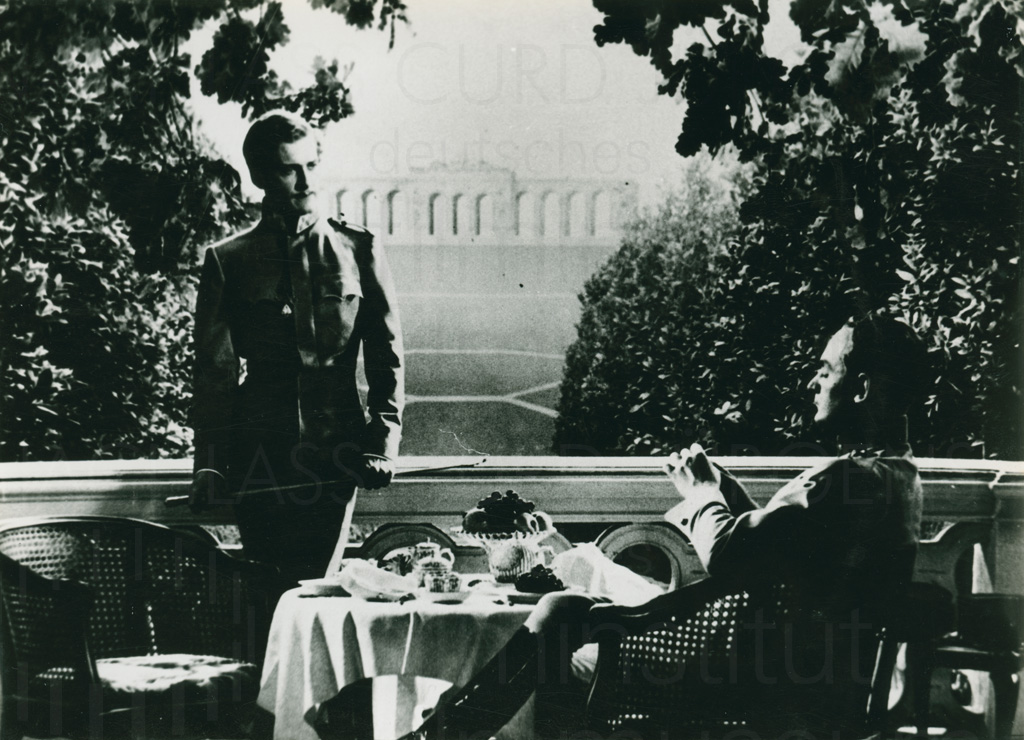

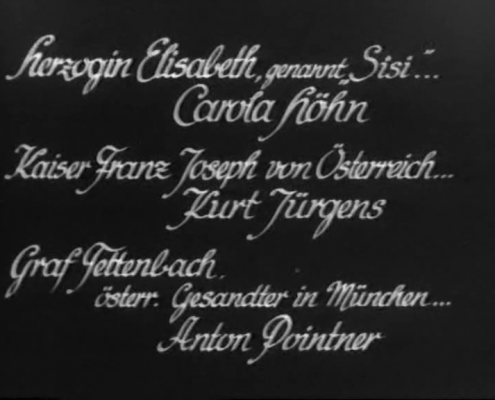

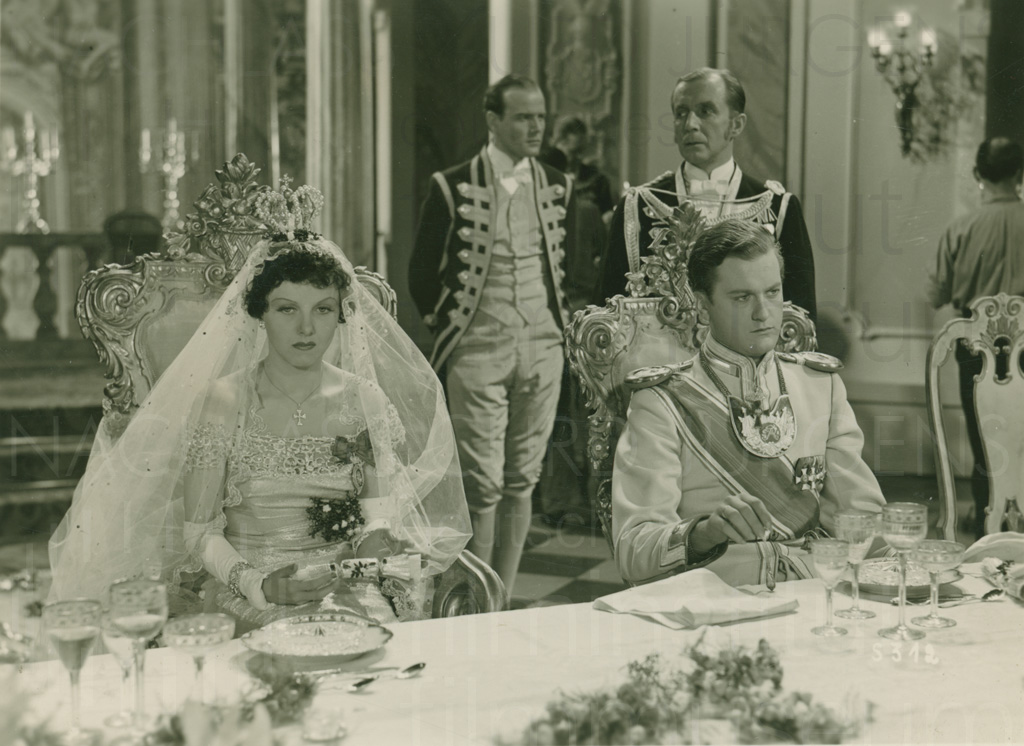

With the Mozart film, WEN DIE GÖTTER LIEBEN (1942), Curd Jürgens was allowed once again to showcase his blinding presence and human warmth as Emperor Joseph ll in a baroque setting. Dialogue scenes such as those with his valet Strack (Paul Hörbiger) and with Mozart (Hans Holt) work both atmospherically and as acting. The film was made in 1942 under Karl Hartl’s brilliant direction. It premièred in proper style in the Gloria Palast on the Upper Kurfürstendamm on the 21 January 1943 and ran for 33 days

The final title EIN GLÜCKLICHER MENSCH (1943) was preceded in the production phase by others like “School of Life” or “The Fantastic Professor”. It was also originally envisaged that Emil Jannings would play the professor. From personal acquaintance with Paul Verhoeven’s film, I am of the opinion, however, that Ewald Balser was the better casting, better even compared with the earlier versions made in 1935 in Sweden and 1946 in Denmark. The material is based on Hjalmar Bergman’s 1925 stage play “Swedenhielms” which did not come out in German translation until 1940 as “Der Nobelpreis.” Curd Jürgens’ role as the newspaper reporter Petersen and would-be son-in-law of the professor boasts numerous dialogue scenes imbued with winning presence that were rewarded with 5000 Reichsmarks inclusive of remuneration for rehearsals. With its world première at the Ufa Palast am Zoo in Berlin in the middle of October 1943, the film ran for 26 days.

With the film EINE KLEINE SOMMERMELODIE (1944) Jürgens was given a starring role alongside the already successful, pretty young blond actress, Irene von Meyendorff, under the direction of the actor-director Volker von Collande. Under normal conditions, it would certainly have resulted in him being built up into a star with the Tobis film company, as should have been expected after FAMILIENPARADE. But it was war time. As a soldier on short-term leave, in civilian life a composer, he is given the chance of making a recording in the radio centre in Berlin. He meets and falls in love with a young telephonist, spends a weekend with her on a sailing boat on the River Havel. They lose contact with each other because he must return to the front, only knowing each other’s first name. Years later – meanwhile she has become a reporter’s assistant and he is in the field hospital – they find each other again thanks to an armed forces radio music programme playing the song “Eva-Maria” which he had composed in memory of the weekend they had spent together, and there is a happy ending. The film was released by the censors on 17 April 1944 and a promotion and press booklet had already been prepared – curiously there is mention made of the “new face in film Curd Jürgens” although he had already appeared in a dozen films.

But the film never had a première or distribution. The reason was – though official sources of course never admitted it expressly – that historical and military-geographical references made in the scenario at the time the film was made could not be reconciled with present realities and would not be accepted by the audience without criticism. Irrespective of this, the film contains an astonishing number of improbabilities, and even downright impossibilities, in form and content which reflects badly on its authors. However, Curd Jürgens was spared having to appear in public at the time, wearing a sergeant’s uniform.

EINE KLEINE SOMMERMELODIE (1944) Film stills

Although there are demonstrable gaps, amongst them one short feature film, which will be the subject of subsequent potentially interesting additions later, I would now like to close these reflections on the catalogue of Curd Jürgens’ first ten years in film. In any case, it can be taken as proven that Curd Jürgens’ film career had already had a powerful start with more than a dozen films before 1945.

Extract from: “Berlin and Vienna. Sketches regarding a Career 1935-1945” of Eberhard Spiess. In: Hans-Peter Reichmann (ed.): Curd Jürgens. Frankfurt am Main 2000/2007 (Kinematograph No. 14).

Notes:

[i] See: Curd Jürgens: … und kein bißchen weise. Autobiographischer Roman. Locarno 1976, p. 177-179.

Translation: Elizabeth Ward