THE ROLES IN UNIFORM

By Rudolf Worschech

The Roles in Uniform

By Rudolf Worschech

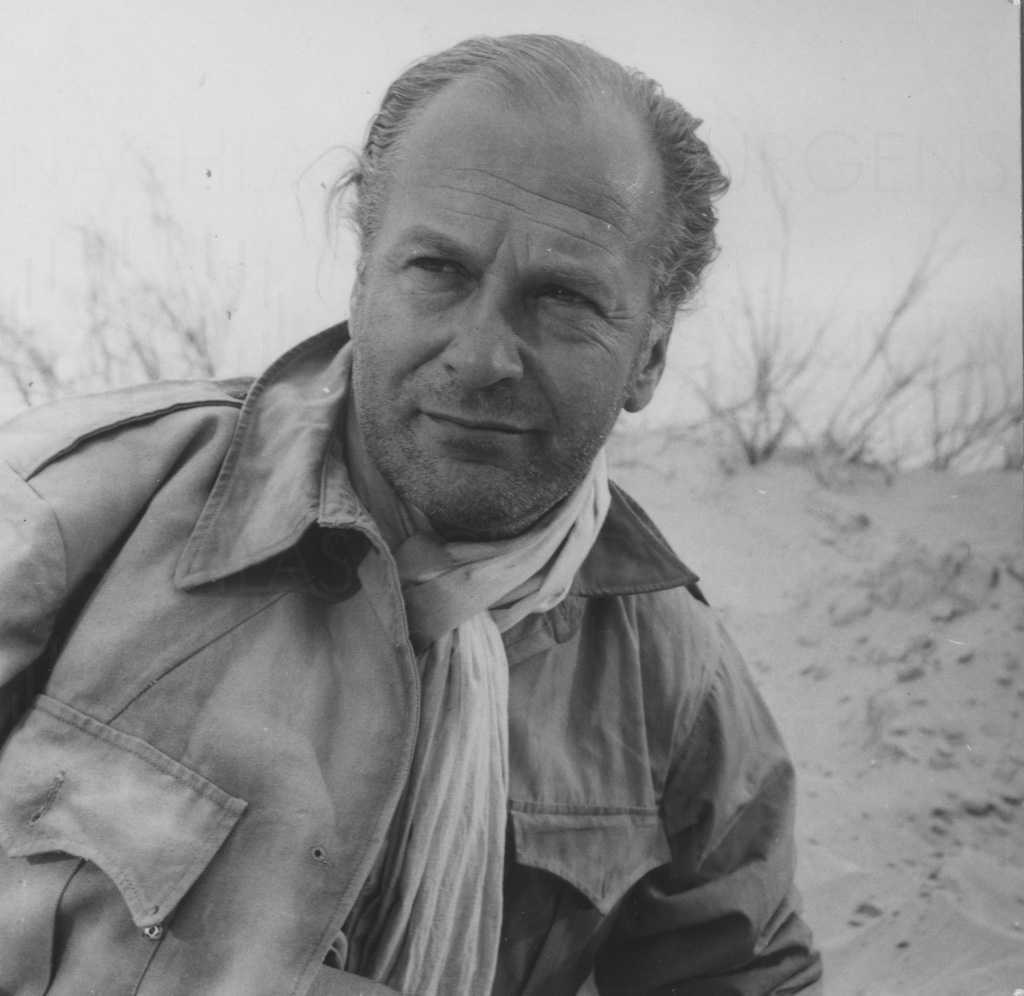

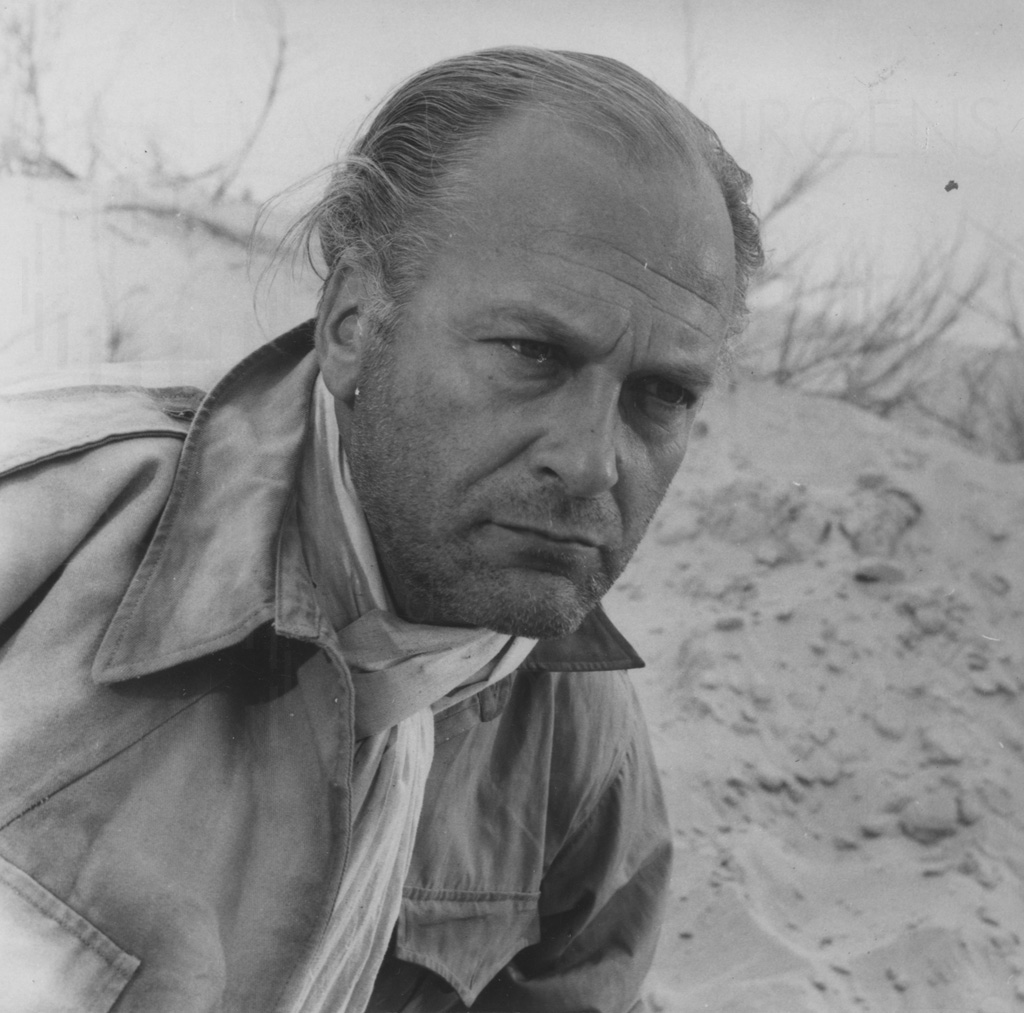

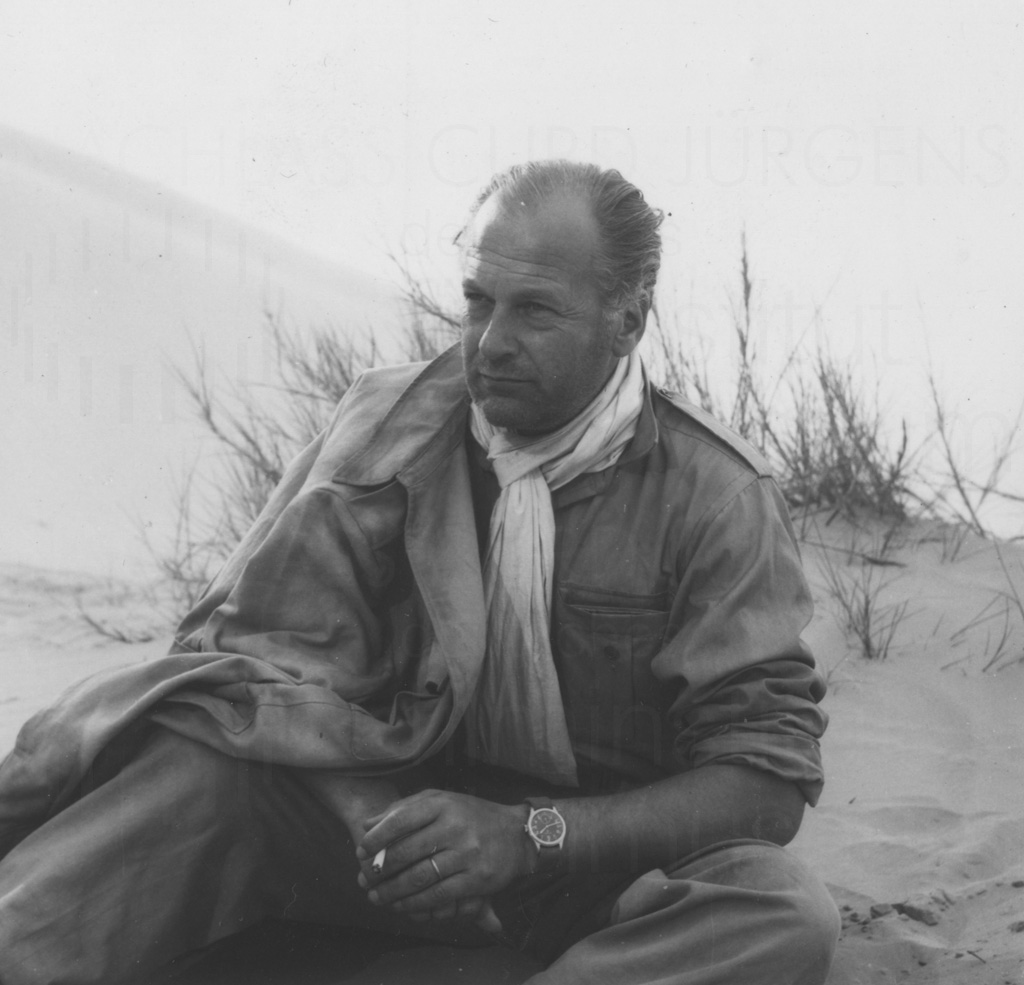

Both LIEBE OHNE ILLUSION (Love Without Illusions, 1955, D: Erich Engel) and TEUFEL IN SEIDE (1955, D: Rolf Hansen) contain passages that are redolent of military life. A note of the barracks square creeps into the former when Jürgens’ boss pays him a visit; in TEUFEL IN SEIDE the characteristic style of his wife’s lawyer is clearly military when he constantly talks of “duty”. And Jürgens stands there as a contrasting figure. It was also a military role which predestined him for his international career: General Harras in Helmut Käutner’s film version of the stage play “Des Teufels General” by Carl Zuckmayer. In 1955 he received the actor’s prize at the Venice Film Festival for this role, alongside his performance in Yves Ciampi’s LES HÉROS SONT FATIGUÉS (The Heroes Are Tired / Heroes and Sinners).

A decade after the horror of the Second World War and the Nazi terror, there came scenes from the inner life of the German armed forces. The first – foreign – war films reached cinemas in the early 1950s, connected with the overall remilitarisation of society and German producers followed in their wake. “Nothing suits a man so well as a uniform”, this Prussian motto matched the tall, blond, blue-eyed and always somewhat stiff-looking Jürgens. DES TEUFELS GENERAL (The Devil’s General, D: Helmut Käutner) is Jürgens’ most dashing role. More than in any other film he dominates space; more than in other films he involves his whole body.

Debates about the crimes of the German Wehrmacht were unknown in the 1950s and the films described how people organised themselves or bluffed their way through (the 08/15 trilogy); how a cadet rebelled against his incompetent superior (HAIE UND KLEINE FISCHE, 1954, D: Frank Wysbar); or how people were immediately occupied in heroic resistance (CANARIS, 1954, D: Alfred Weidenmann). In 1955, ten years after the end of the war and eleven years after the execution of Count Stauffenberg, two films arrived in German cinemas with treatments of the failed attempt on Hitler’s life in 1944: DER 20. JULI by Falk Harnack und G.W. Pabst‘s ES GESCHAH AM 20. JULI. That this conspicuous treatment of resistance functioned as psychic catharsis is self-evident.

In DES TEUFELS GENERAL Harras is portrayed as the natural antagonist of the Nazi regime. A daredevil and a drinker, impertinent (“A toast with an empty glass – the Führer doesn’t drink”), very much a ladies’ man, an individualist who does not wish to comply with the totalitarian society, perhaps only because he finds Hitler abhorrent. And yet the film describes him as a fellow traveller, a supporter of the Nazi armament campaign and a rather helpless rebel against it. Jürgens’ strength in this film lies in his outbreaks of temper, in his vacillation between two states, as when Harras constantly swings between compliance and (verbal) disobedience. Harras can be militarily decisive, what might be called “spirited”, but at the same time reveals to the actress Diddo Geiss (Marianne Koch) an unaccustomed softness.

Käutner built a subtext about old age into the role of Harras. Harras is certainly not a “flyer” any more as he was once in the First World War, and DES TEUFELS GENERAL likes to tell us this; he still has in his possession the watch of the first enemy pilot he shot down. He tells Marianne Koch that he is not a monument, thereby trying to bridge the age barrier between the twenty-year-old actress (who looks at least thirty years younger) and himself. The erstwhile pilot is now “general air chief” and apparently all that lies behind this pompous title is a desk job and public imaging. More than in any other film, Jürgens here is reminiscent of John Wayne who at much the same age also played a great ageing role: in John Ford’s SHE WORE A YELLOW RIBBON (1953). Harras’ suicide seems to be not only a consequence of the hopeless position he finds himself in having been forced to betray his friend who had sabotaged bomber production; his self-chosen death in the aeroplane is also the end of the drama of a man chasing his youth.

This hidden melancholy of ageing and a natural aversion to what National Socialism embodied predestined Jürgens for other uniformed roles, above all in international projects. He was perhaps not so much the good German as the subversive Prussian: An individualist standing out from the collective. He came to represent the enlightened part of the German Wehrmacht and it was this which constituted his attractiveness. Even as a German army officer, he was urbane and did not exude the smell of the barracks. At the same time he embodied the positive military virtues of loyalty, courage and camaraderie. With the exception of BATTLE OF BRITAIN (1969, D: Guy Hamilton) he rarely played dyed-in-the-wool Nazis. STEINER – DAS EISERNE KREUZ II. TEIL (Breakthrough, D: Andrew V. McLaglen) from 1978/79 even lends him the attribute of soldierly resistance when, against the backdrop of the Hitler assassination attempt, he seeks out an armistice with the Americans and shoots himself when he fails. His Major General Blumentritt in THE LONGEST DAY (1961/62), an upbeat invasion panoptic with German sequences staged by Bernhard Wicki, makes fun of the General Staff’s conduct of the war and their subjection to the moods of the Führer.

In THE ENEMY BELOW by Dick Powell from 1957, Jürgens is the “Kaleun” (Capitain‘s Lieutenant) of a German U-Boat, who can only manage a tired smile for “Führer command, we will follow you” on his command bridge. THE ENEMY BELOW is about two men who learn to respect one another: one of them, Robert Mitchum, is on board a US destroyer, the other, Jürgens, is under the sea. Among the strengths of both actors is the skill of acting with minimal facial movement (a trait used by Mitchum in his films more than by Jürgens). The submariner’s strengths lie in waiting and listening; as a result, Jürgens has plenty of opportunity for stoical composure in this film. He is a paradigm for virility here, a man who makes the right decisions and is unbroken, who acts instead of engaging in discussion.

In BITTER VICTORY (1957), Nicholas Ray disavows the Jürgens myth of sincerity, courage and loyalty. Here too it is about the confrontation of two men; again, as so often, there is a love triangle. Jürgens plays a British officer, Major Brand, who, with Captain Leith (Richard Burton), is leading a commando operation to infiltrate a German stronghold in the Libyan desert. Brand is married to a woman with whom Leith at one time was in a relationship. The confrontation is programmed but ensues from the characters: Leith is a misanthropic cynic and Brand a bureaucrat – above all a coward. While attacking the Germans he hesitates too long when he has to overpower a sentry (the dagger shakes in his hand) and Leith has to take over. Leith reflects the weakness of his superior. Both men are caught in a vicious circle. Brand tries to eliminate Leith and the captain provokes him. Jürgens does not appear as uncertain in any of the other uniformed roles as in BITTER VICTORY. He is totally turned in on himself alone, more strongly than in DES TEUFELS GENERAL, and his men do not stand behind him. Torturing himself with the question about whether Leith could use his weakness to tarnish his reputation at head quarters, he tries to use his higher rank to dispose of Leith, leaving him behind with the wounded; and he does not give a warning when he sees a scorpion come scurrying towards him. An “empty uniform” – Leith calls him at one instance. Brand can only command respect because of his position of power: he is not a natural figure of authority. The film reveals practically nothing of Brand’s previous history: he is a professional soldier. We learn considerably more about Leith. Nonetheless, it is Jürgens achievement that Brand is able take on definite tragic traits and that his self-hatred is apparent within him.

With Richard Burton

With Ruth Roman and Richard Burton

With Ruth Roman

With Ruth Roman

With Richard Burton and Ruth Roman

With Richard Burton in BITTER VICTORY (1957; D: Nicholas Ray)

Transcript & audio

[Last sentence, p. 1:] Am meisten beeindruckt hat mich einmal Richard Burton, als er sich, damals noch verhältnissmäßig […]

[…] unbekannt, nach 3-monatiger gemeinsamer Arbeit an “Bitter Victory“ im Nizzaer Studio Victorine, am letzten Tag von mir verabschiedete „Danke Curd. Und danke auch, weil ich viel von Dir gelernt habe“. Obwohl mir damals nur die ungewohnte Floskel auffiel, hat er mir später gestanden, viele Jahre später als er mit Liz Taylor uns nach einer Gala-Premiere von “Widerspenstigen“ in der Pariser Oper, in ihr Appartement im Plaza Ath[é]née eingeladen hatten, morgens nach endlosen Whiskies, dass er es damals ernst meinte. Nur hatte er es mehr auf meine Lebensgewohnheiten bezogen als auf meine schauspielerische Leistung. Auf die Parties, die ich in ’Canzon[e] [verm. gemeint ist “Casszoun”] del mar’ gab, auf die Mädchen, die immer da waren, wenn man sie brauchte, “Jahrelang habe ich Dich als Vorbild genommen, Curd, jetzt habe ich Dich überflügelt“. Ja das ist wahr. Das hat er. Aber wenn ich es mit Bitterkeit zugebe, so ist kein Neid dabei. Es ist nur ein Baustein mehr in dem Puzzle, das ich zusammen setzen will, indem ich versuche mir zu erklären, warum ich jetzt hier alleine sitze

BITTER VICTORY is among the best films in which Jürgens was involved. Perhaps his most moving performance is in ME AND THE COLONEL (1958) by Peter Glenville. This film is a caricature and, at the same time, also the epitome of all his roles in uniform. Again two men confront one other, but they are bound together by circumstance, two men who could not be more different but who in the end move closer to one another: the Polish Jew Jakobowsky (Danny Kaye), fleeing from the Nazis through Europe and ending up in Paris just before the invasion, and the Polish colonel Prokoszny (Jürgens), a member of the old aristocracy and an anti-Semite to boot. If Jakobowsky is a realist with good organisational skills, then Prokoszny is a Don Quixote who, when he is asked if he can drive a car, can only answer: “I am a cavalryman!” If Jakobowsky is rather a quiet type, then Prokoszny is someone who loves grandiose words and gestures, a man with nineteenth-century charm (“In the cathedral of my heart there will always be a candle that burns for you”). Jürgens portrays Prokoszny with grotesque exaggeration, he pops his eyes, makes them bulge, pushes his mouth out, clenches his fists and barks out his words so that at times there is even a hint of farce. Jürgens positively booms in this film. It is one of most fascinating traits of Curd Jürgens’ screen personality that an apt portion of self-irony resonates even in his uniformed roles.

Translation: Elizabeth Ward