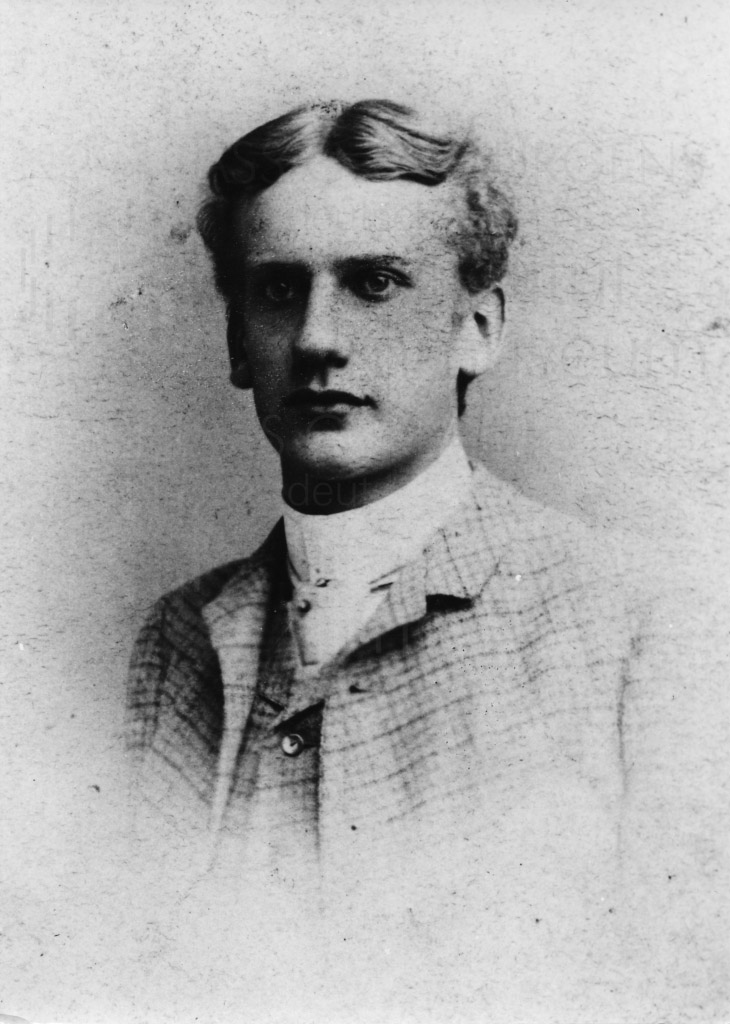

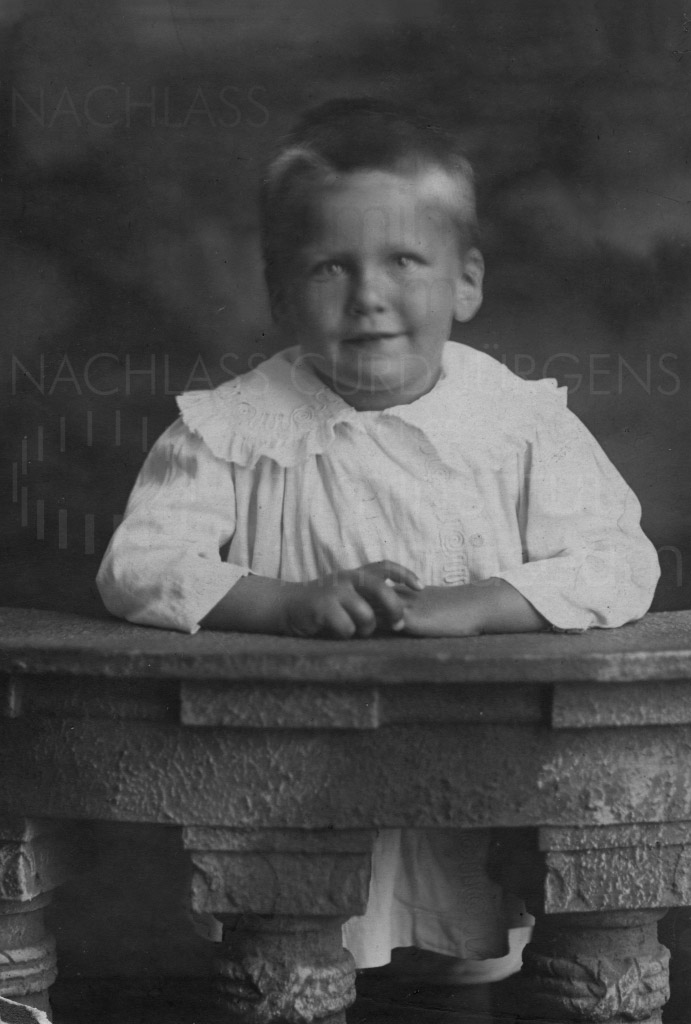

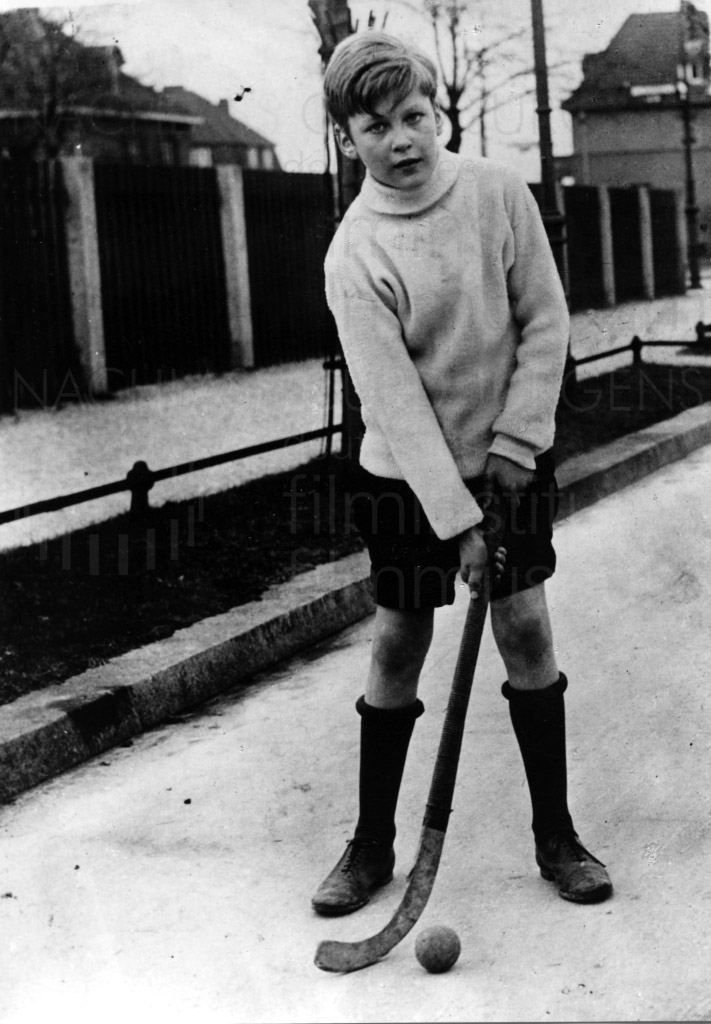

As the only son of a prosperous family from the upper-middle class, Curd Gustav Andreas Gottlieb Franz Jürgens, together with his elder twin sisters Jeanette und Marguerite, lived a carefree young life. The father, Kurt Jürgens, born in Hamburg and of Danish extraction, and the mother, Marie-Albertine, née Noir, a French woman from Évian-Les-Bains, brought up their son to be bilingual, sheltered and cosmopolitan in equal measure.

Perhaps as son and heir, the so-called “Crown Son”, he was even a little spoiled.

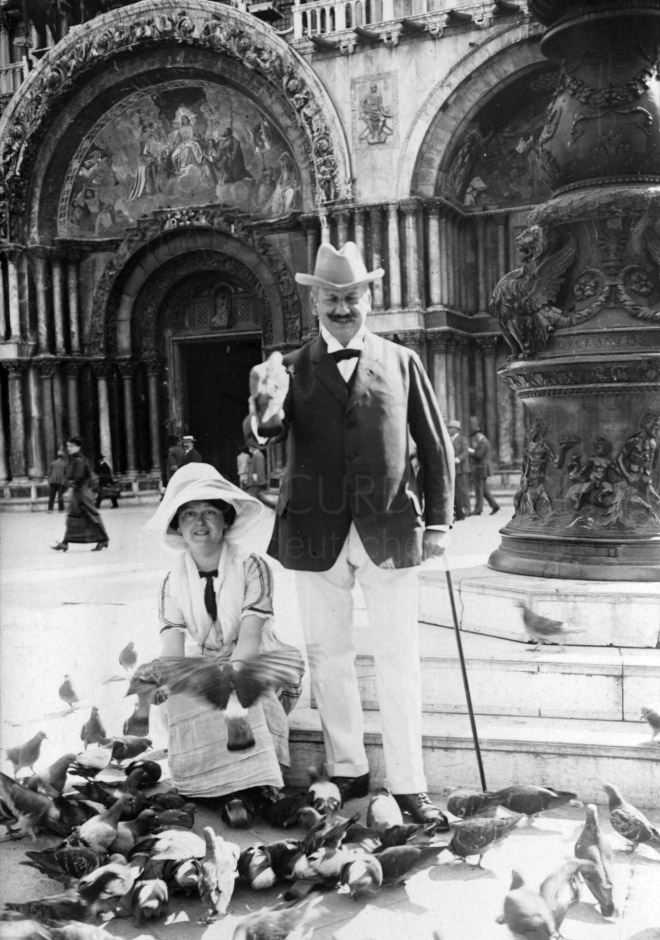

Following highly lucrative business dealings which frequently took him to the far eastern parts of the Russian Empire for long periods after the First World War, the import-trader settled with his family in Berlin. The sisters were born in Lucerne while their parents were travelling in Europe, the boy in Solln near Munich, their first residence in Germany. The mother, who in the time of the tsars had come to Saint Petersburg as a French teacher, had met her husband at one of the many social gatherings and fallen in love. They married at the turn of the century and decided to make their home in Germany. The choice of Berlin suburb which they settled upon was Neu-Westend, a part of Charlottenburg.

The Jürgens Villa

With the unregulated planning measures of the time, the Jürgens Villa – which we can still experience in photographs – must have been an extraordinary dwelling with a middle- and far-eastern character that rejected the outside world. Quick-witted Berliners soon dubbed it the “Turkish Villa”, all the more aptly as the house entrance was decorated in the Arabic letters “Bismillah rahman rahim” or “In the name of Allah the Merciful”.

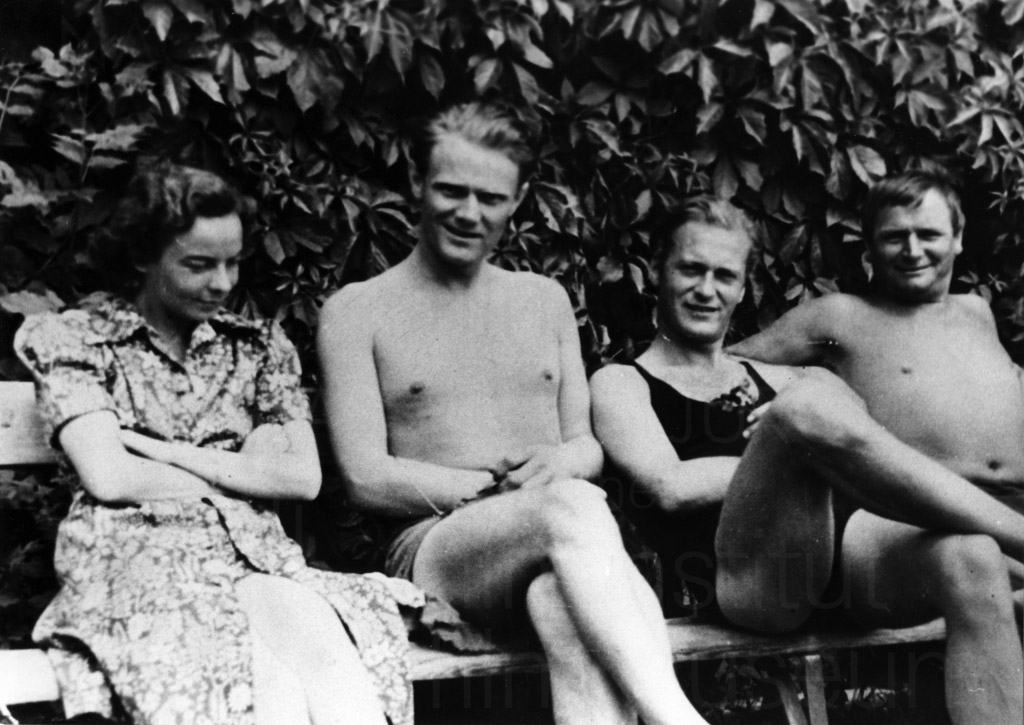

The Jürgens family included a dog, Rachmat, and a friend from Russia they called Uncle Kostia. It was not unusual for them to have caviar and Crimean champagne. The family valued middle-class, hospitable tranquillity to which foreign guests frequently brought an added sense of the wider world.

The son was a pupil at the Herderschule, a grammar school for modern languages in the same area of Berlin and when his academic performance in the senior classes faltered, his father took him aside to give him some advice: “Your children, my boy, won’t have to earn a living. Your father has enough money. And so it is necessary for you to learn a lot. There is nothing more repugnant in life than the stupid rich.”[i] Clever insights like these certainly had an influence on Curd’s life – albeit subconsciously perhaps. Another maxim picked up while was staying with family friends in London ran: “A gentleman is someone who behaves in exactly the same way towards his highest superior as he behaves towards his lowest employee.” His mother’s pragmatism and discernment probably played an important role as well, as becomes clear in her opinion about Napoleon: “Napoleon was a great Frenchman, but he left France smaller when he went than it was before he came.”[ii]

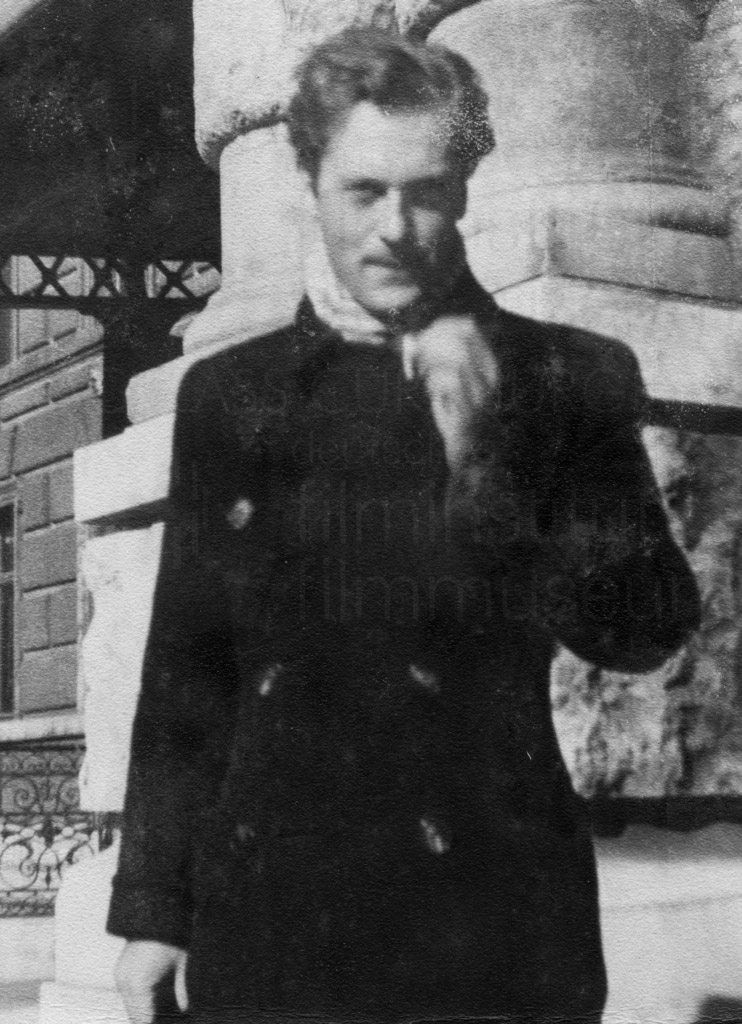

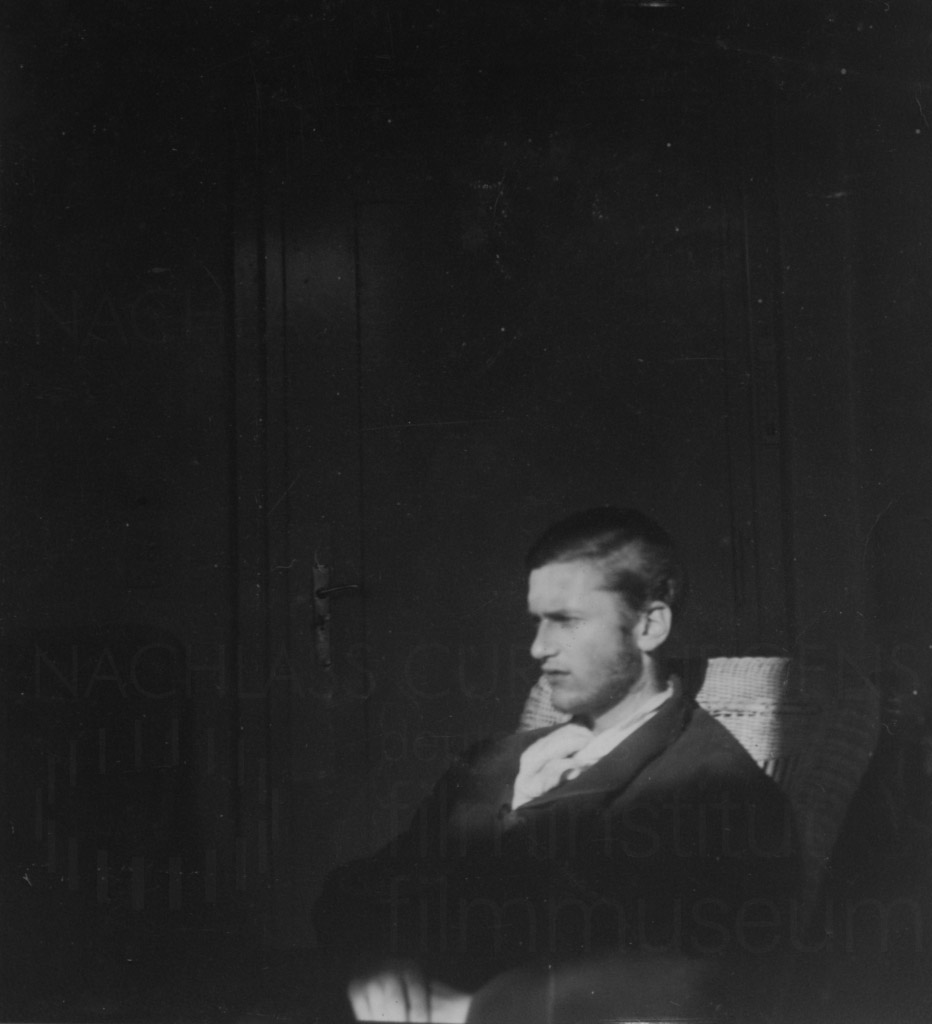

These home and outside influences on behaviour and taste, linked to a good grammar school education, formed the basis for his subsequent professional life which, via a brief detour as a journalist for Theodor Wolffs Berliner Tageblatt, began before 1930. This was about the time when his parents and two sisters emigrated to Barcelona for financial as well as for political reasons. Following his own wishes, he was allowed to stay on for a while in Berlin in the family house despite it already having been sold. This was only thanks to a small monthly allowance paid by the father of his future Jewish brother-in-law. This also allowed him to take his Abitur (school-leaving examination) belatedly after he had been forced to spend a year in hospital following a car crash caused by his brother-in-law. It was only then that his career began, set in motion with acting lessons from the actor Walter Janssen and from the language coach Paul Günther. This was sometimes interrupted by financially lucrative publicity photos for men’s clothing, but never held back.

Extract from: “Berlin and Vienna. Sketches to a Career 1935-1945” by Eberhard Spiess. In: Hans-Peter Reichmann, (ed.): Curd Jürgens. Frankfurt am Main 2000/2007 (Kinematograph No. 14)

Translation: Elizabeth Ward

[i] Curd Jürgens: … und kein bißchen weise. Autobiographischer Roman. Locarno 1976, p. 89.

[ii] Jürgens, loc. cit., p. 110.