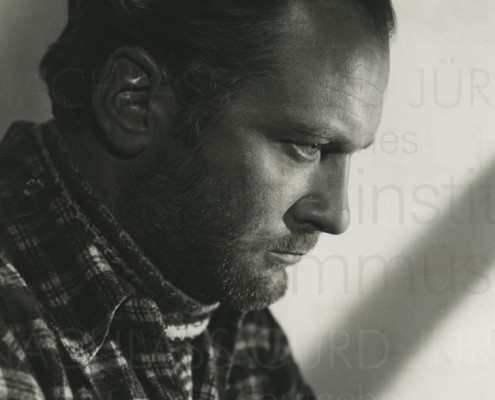

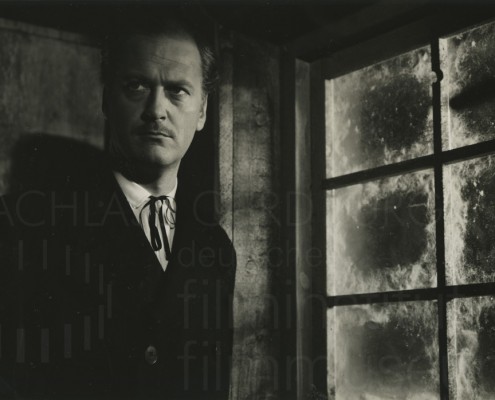

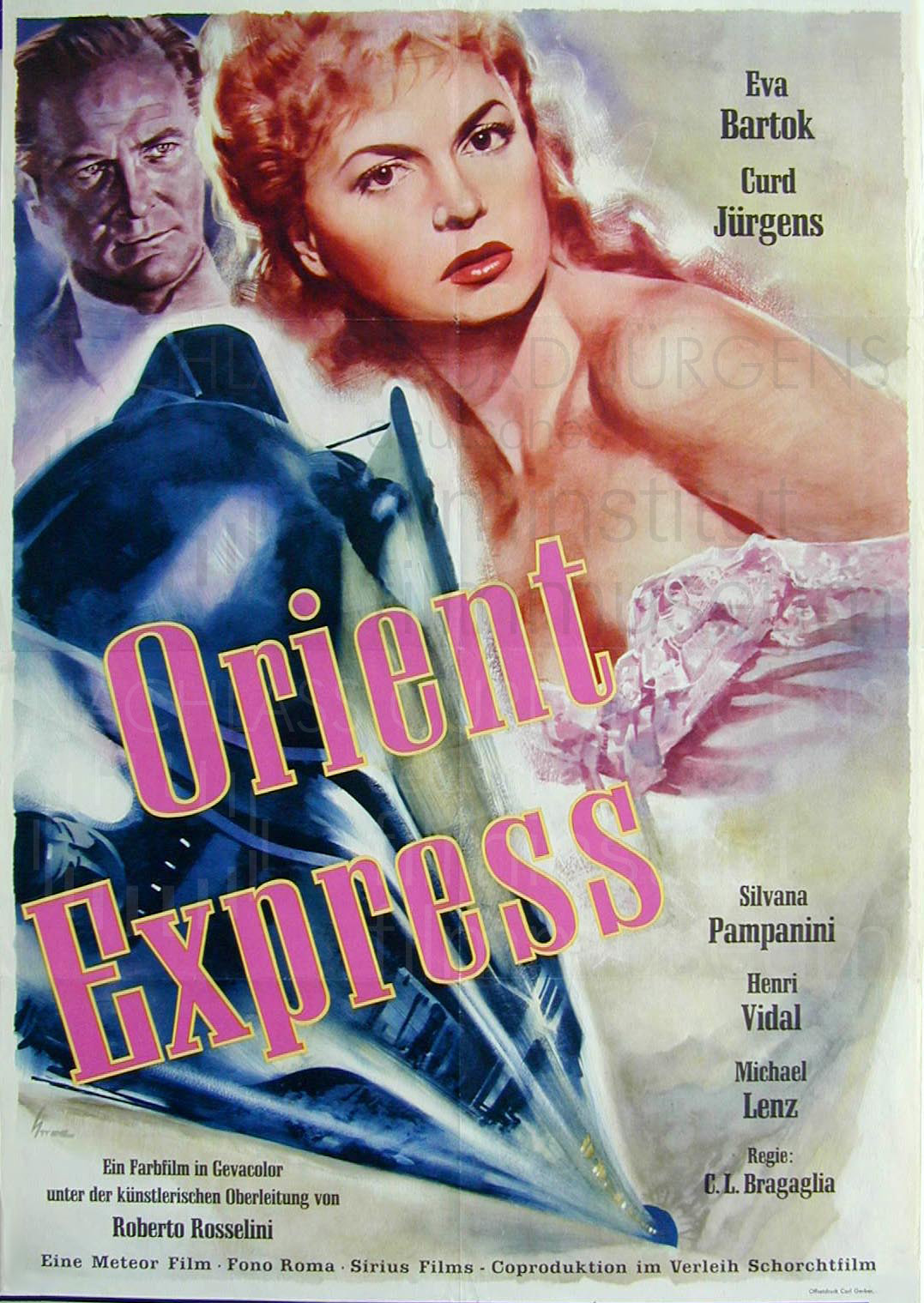

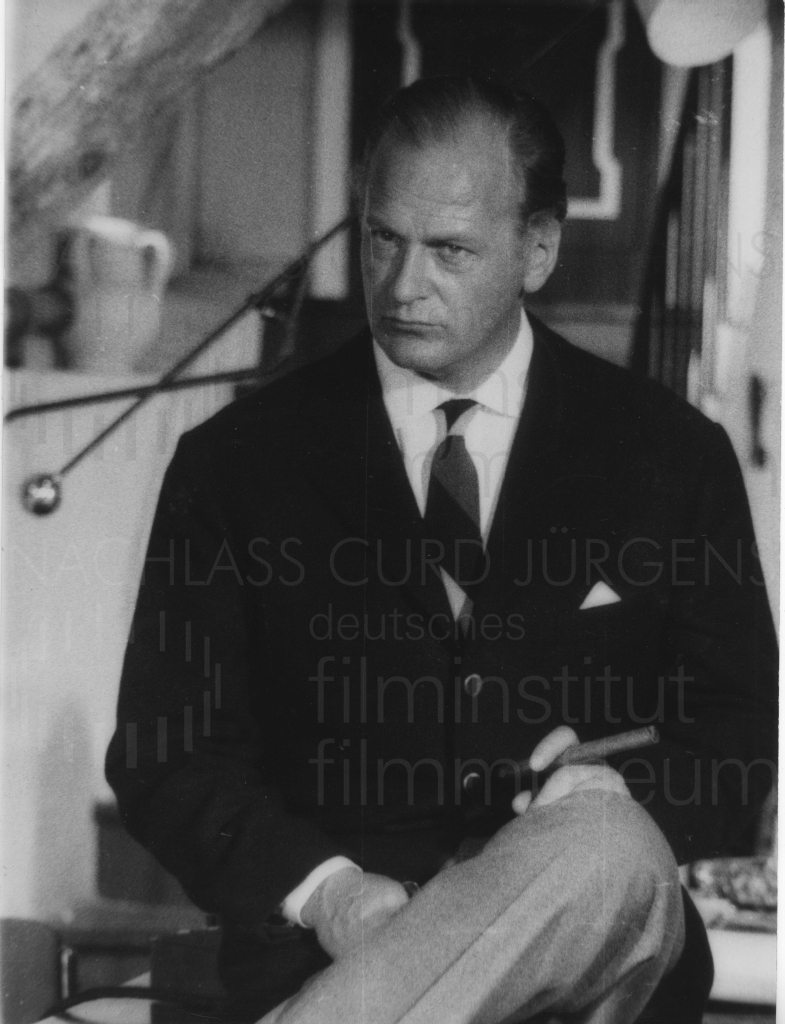

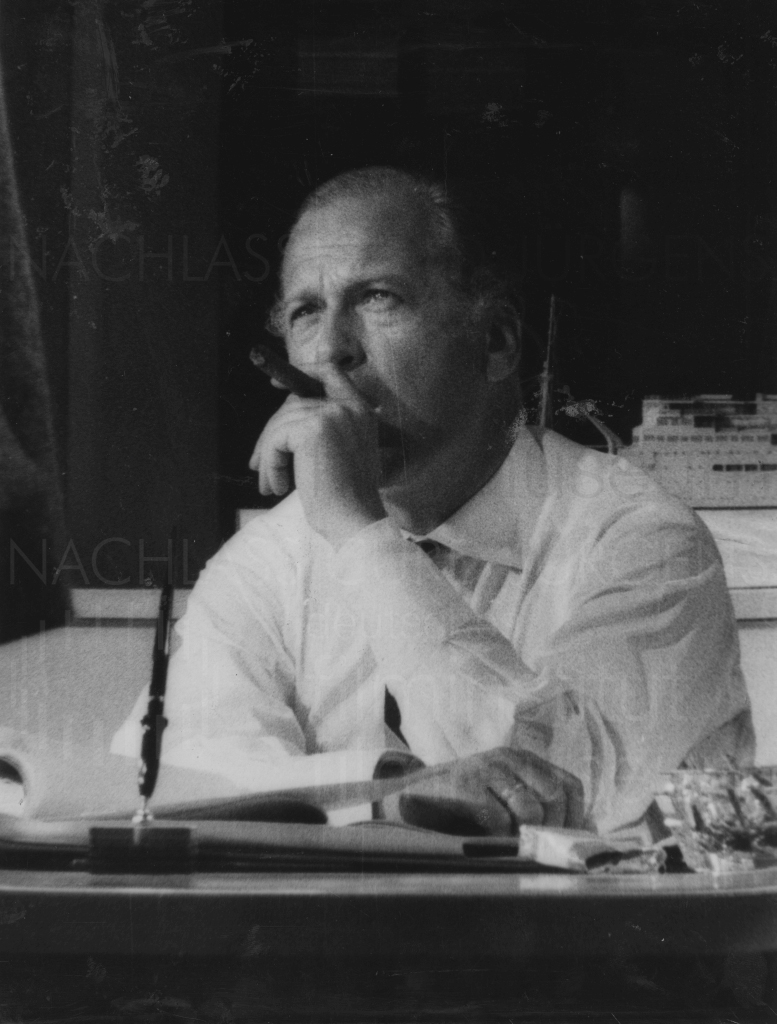

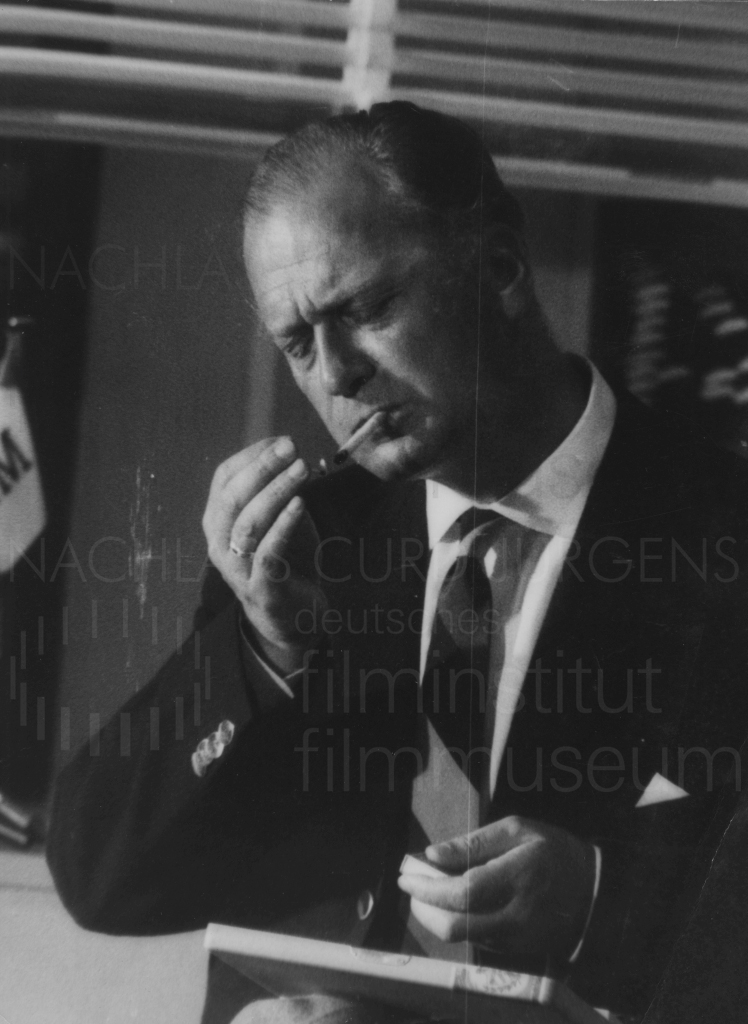

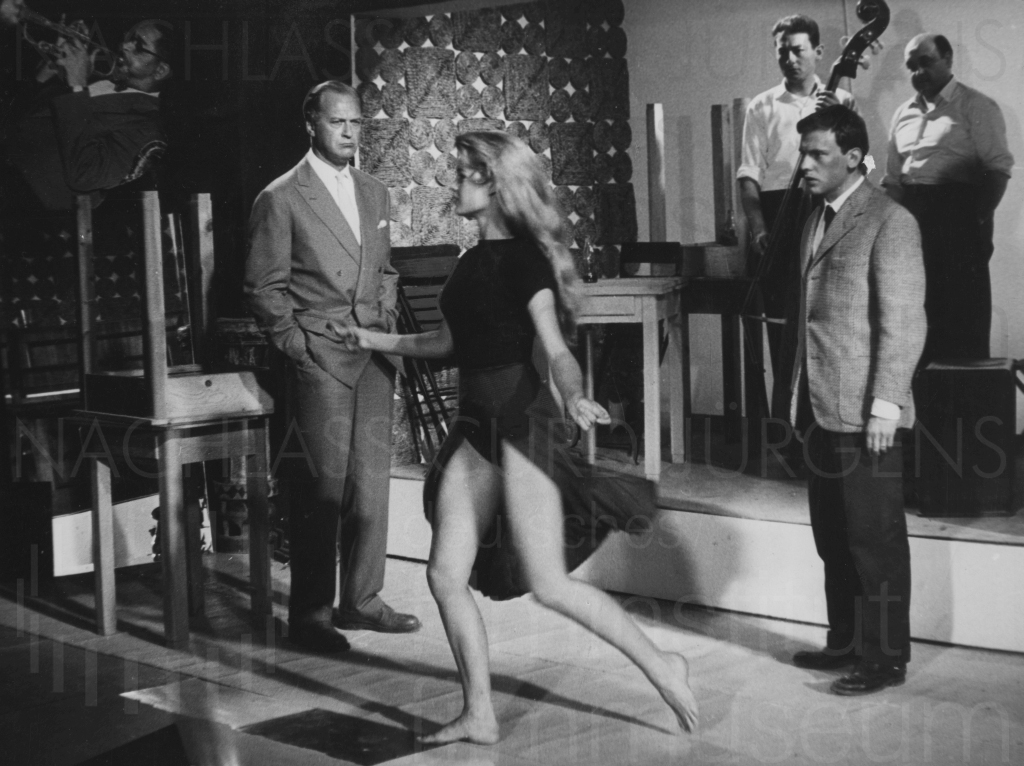

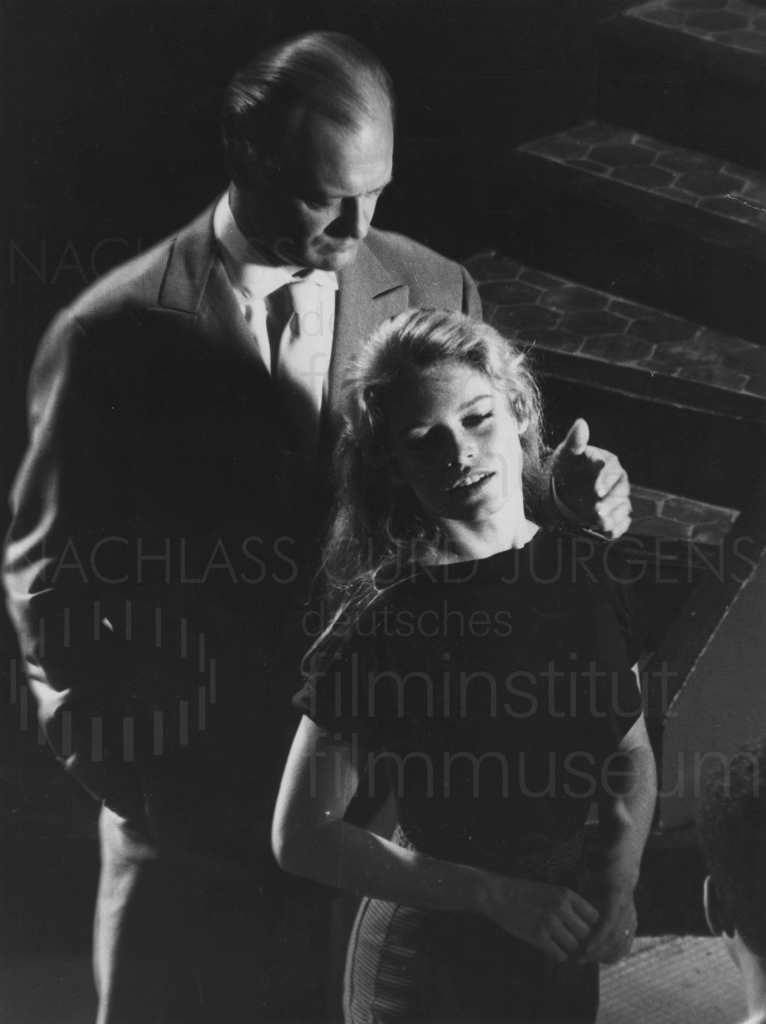

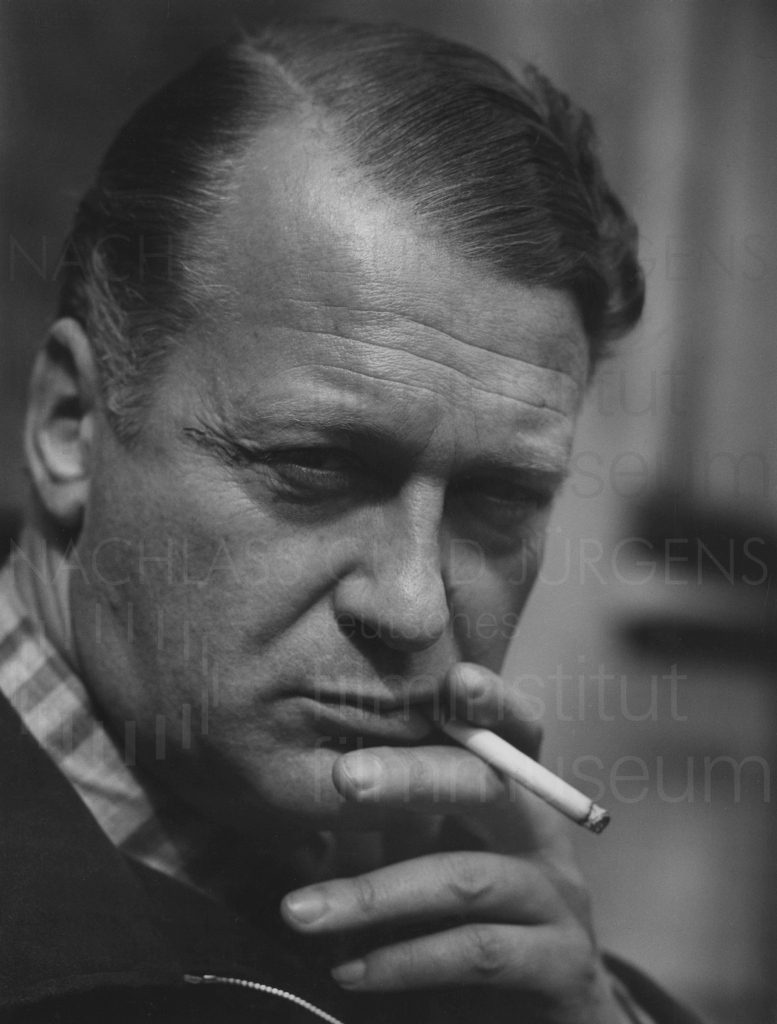

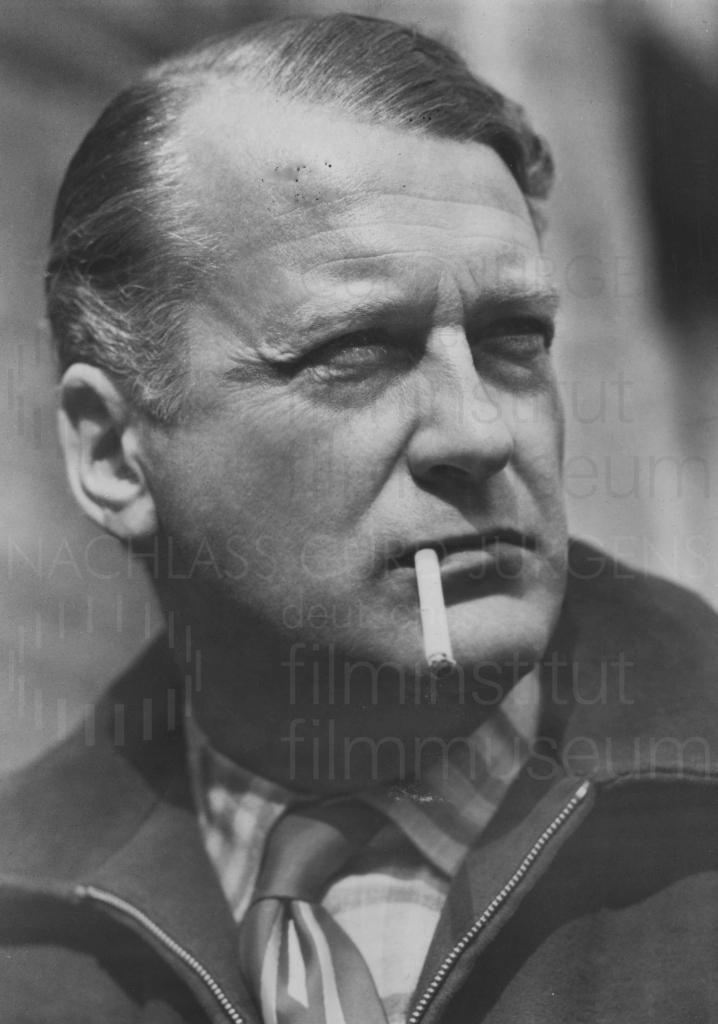

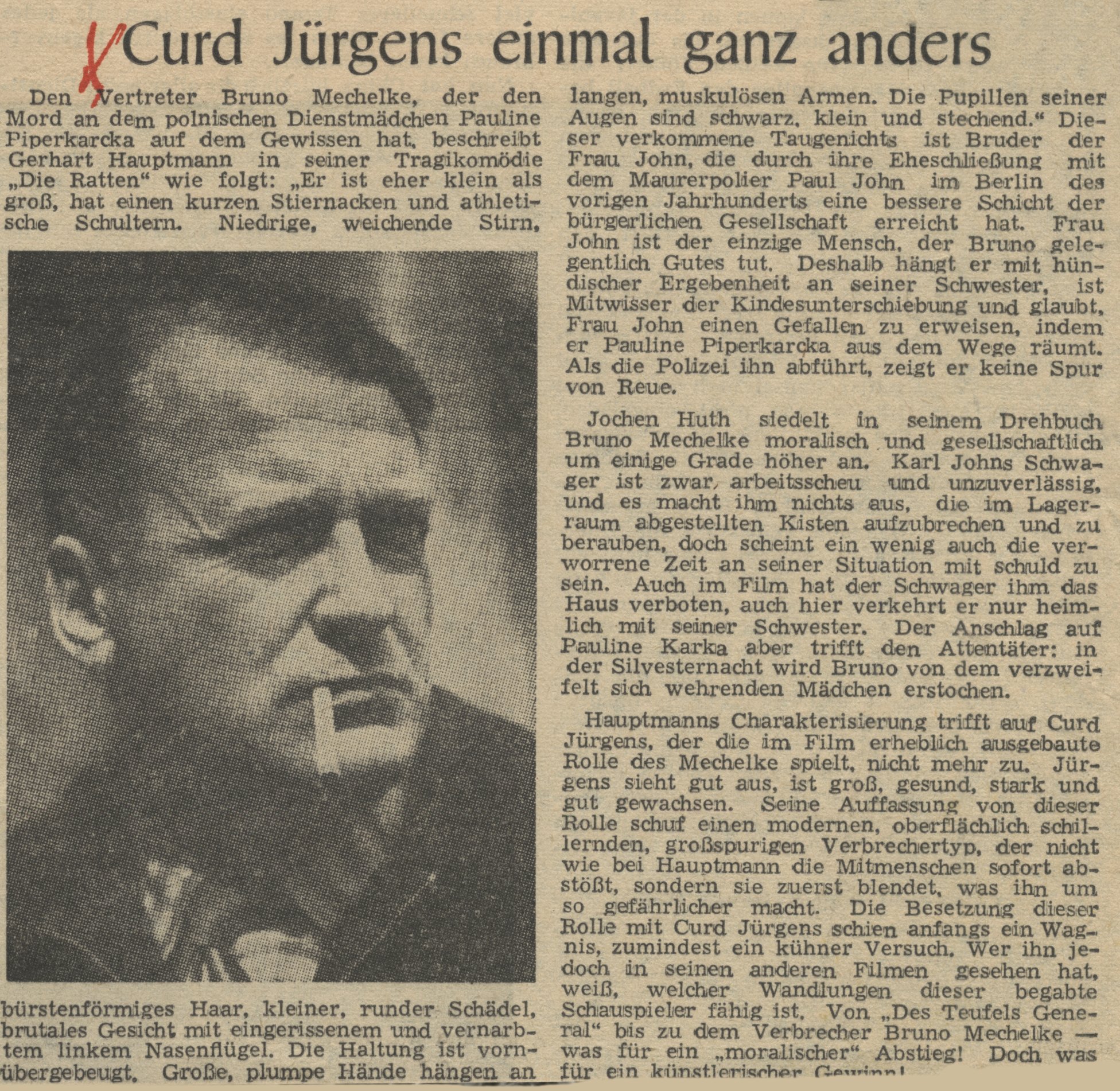

CURD JÜRGENS IN POST-WAR FILM

By Rudolf Worschech

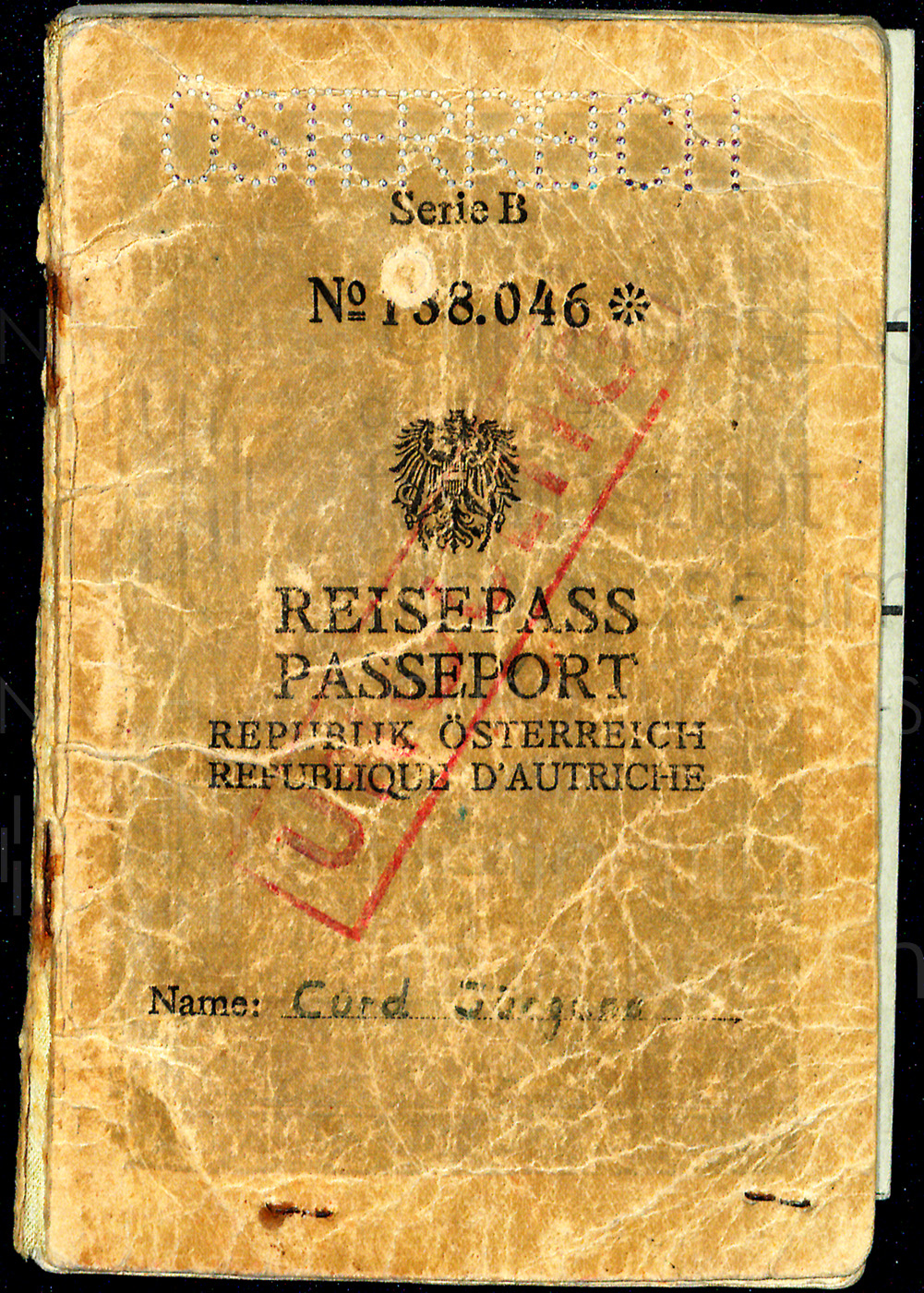

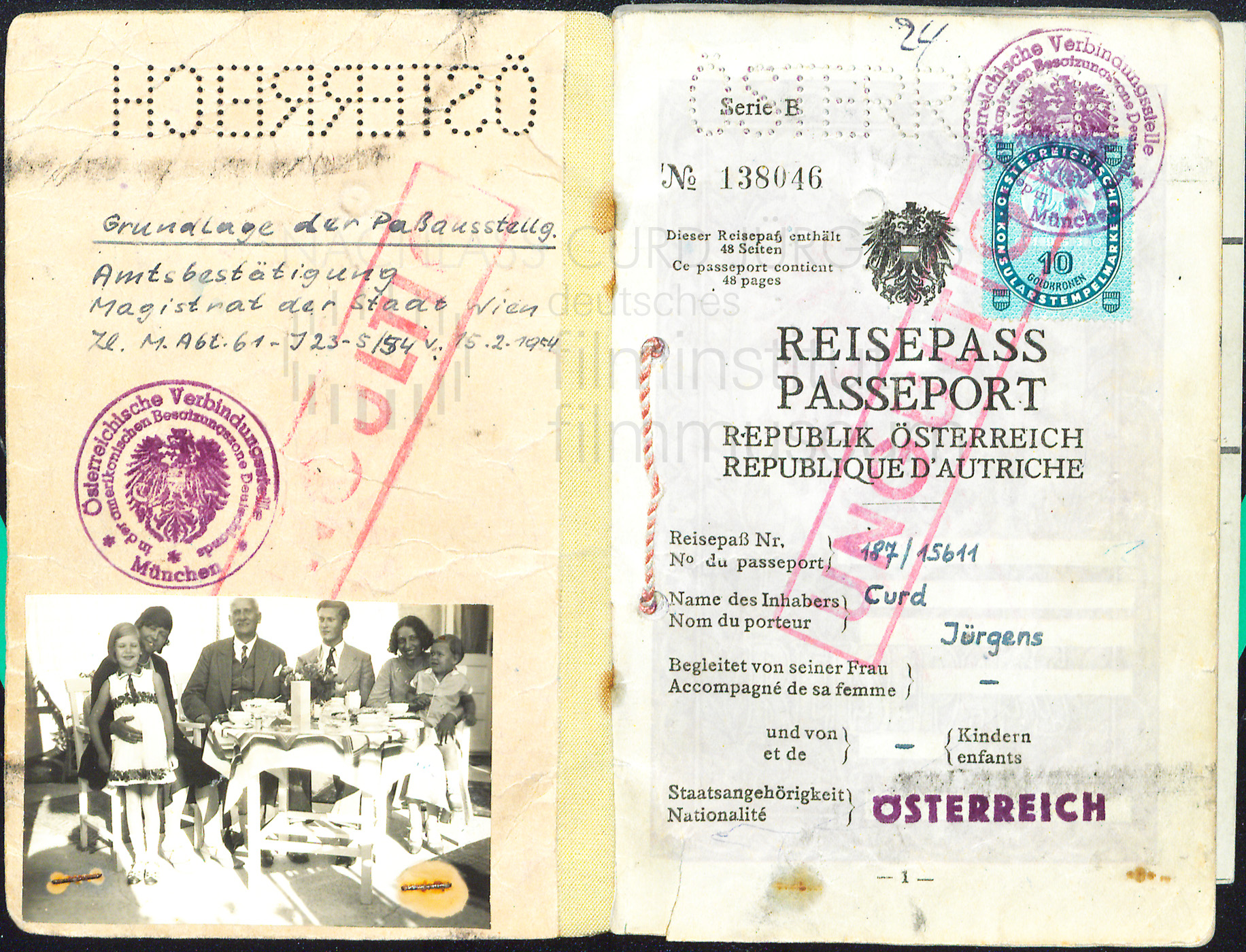

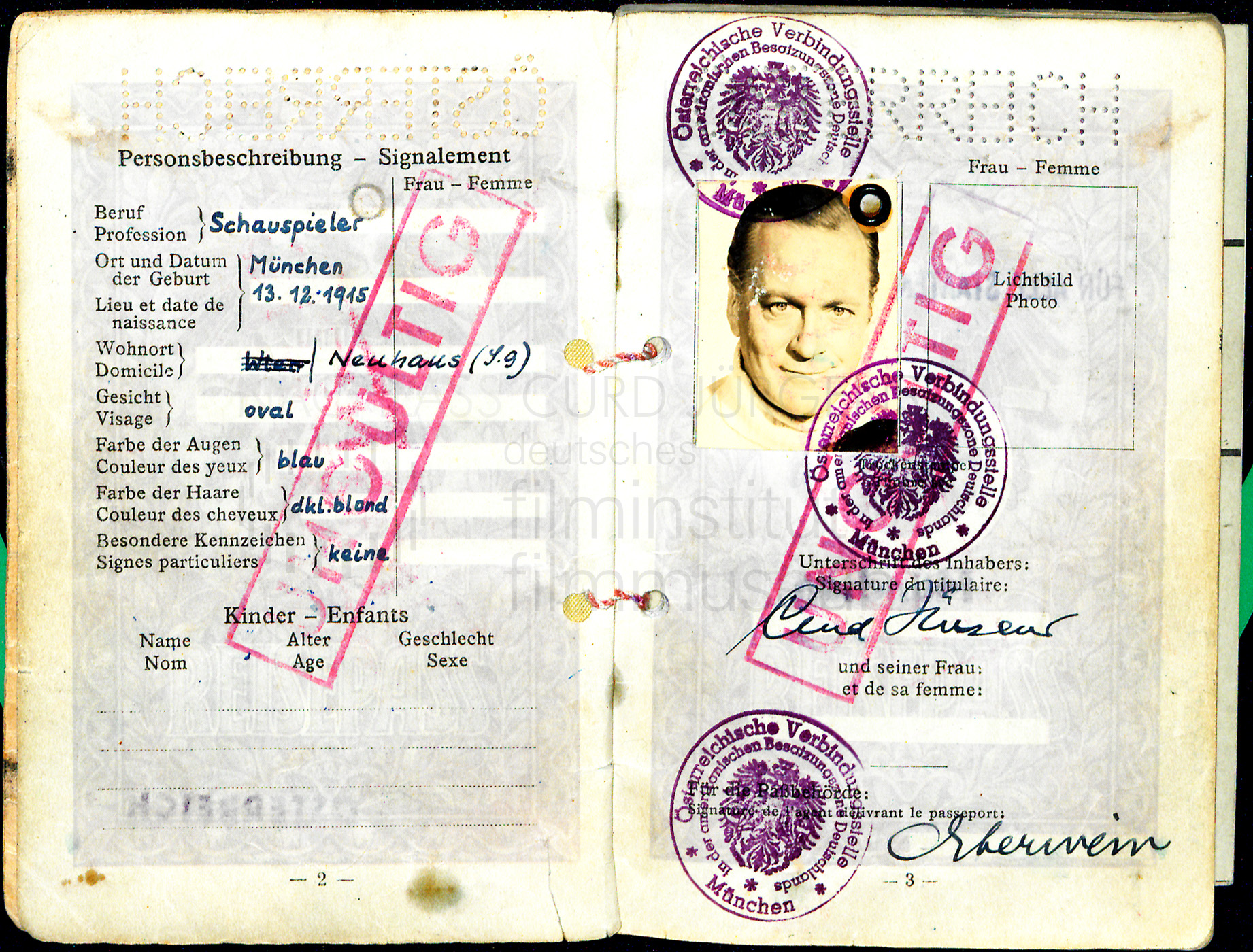

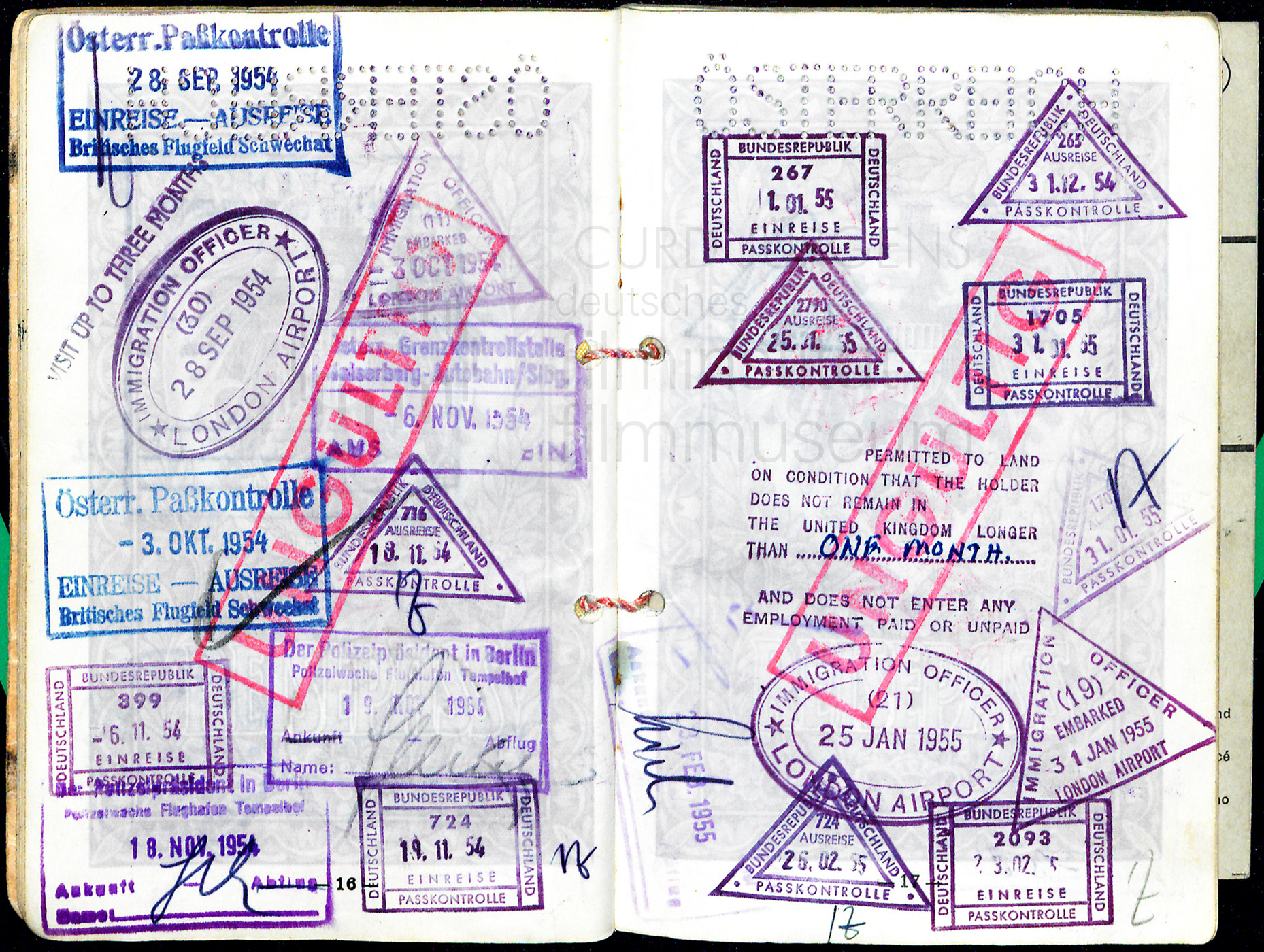

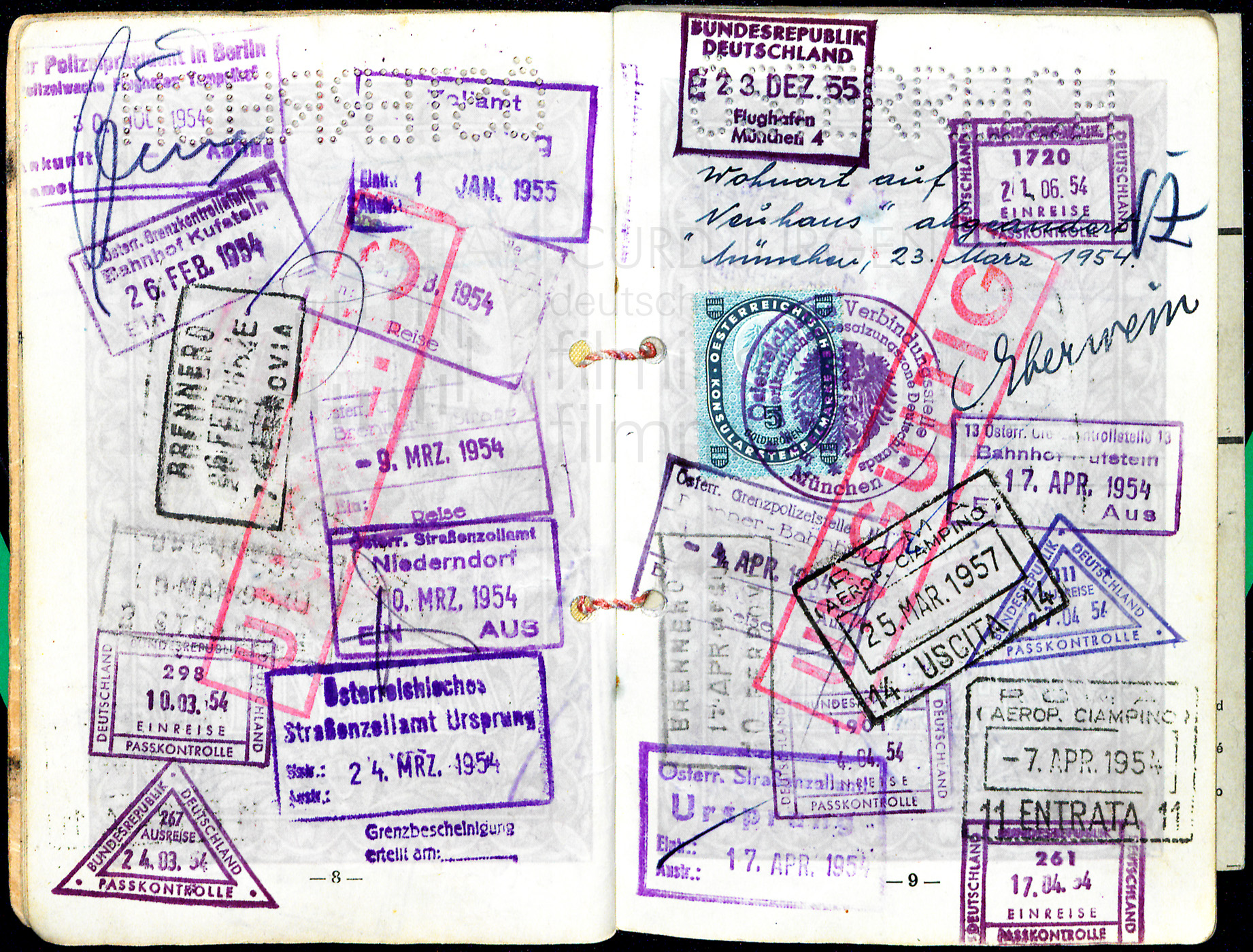

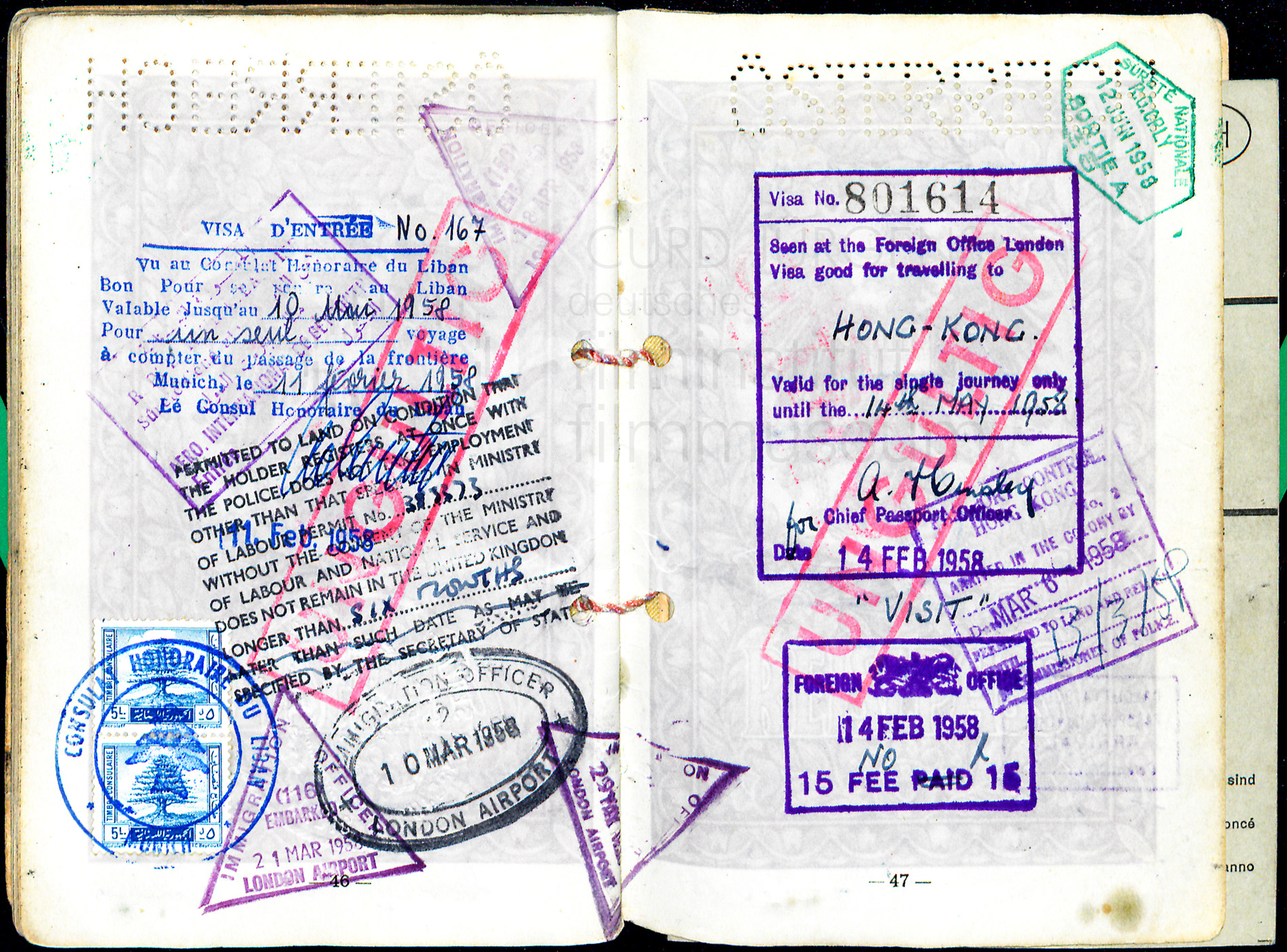

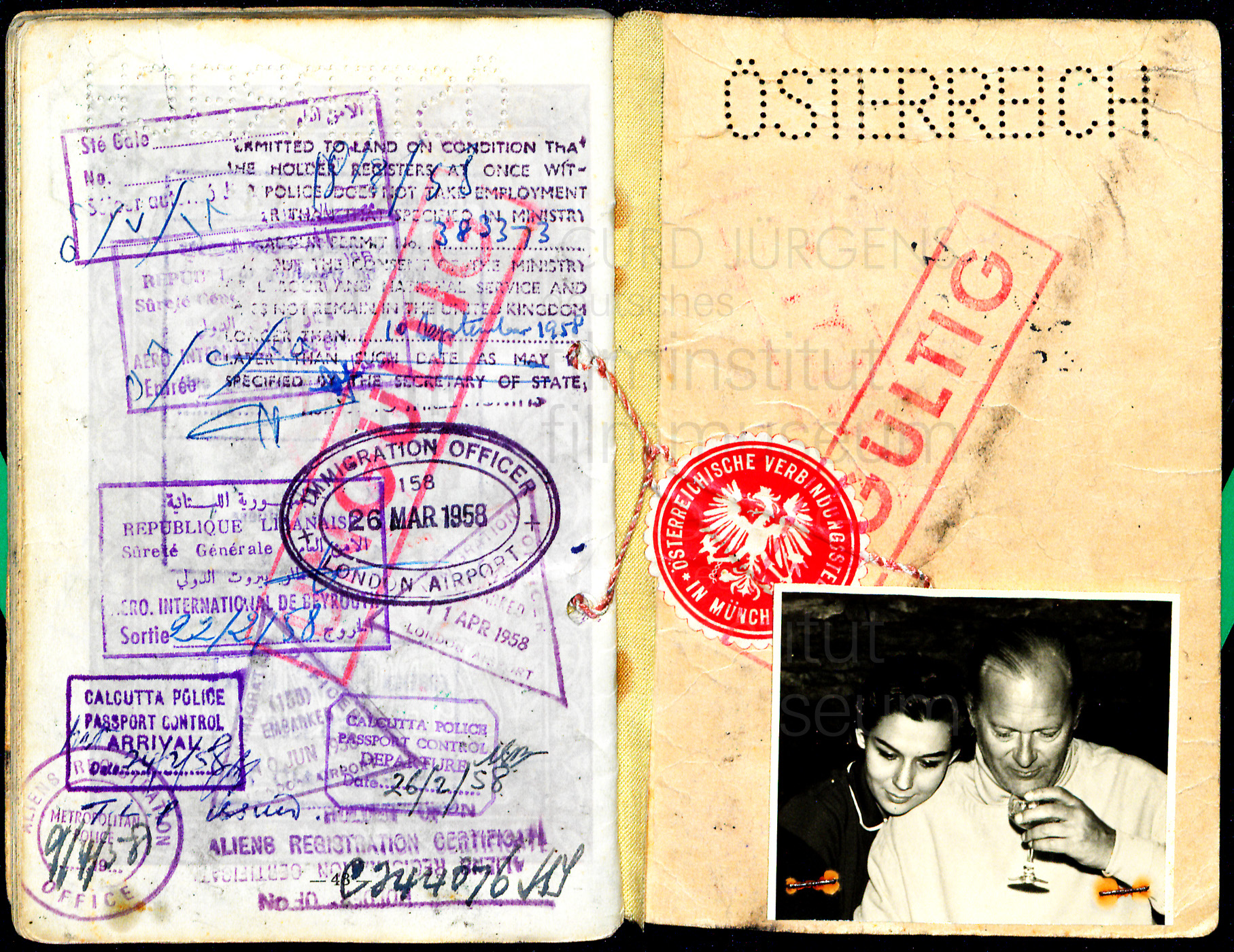

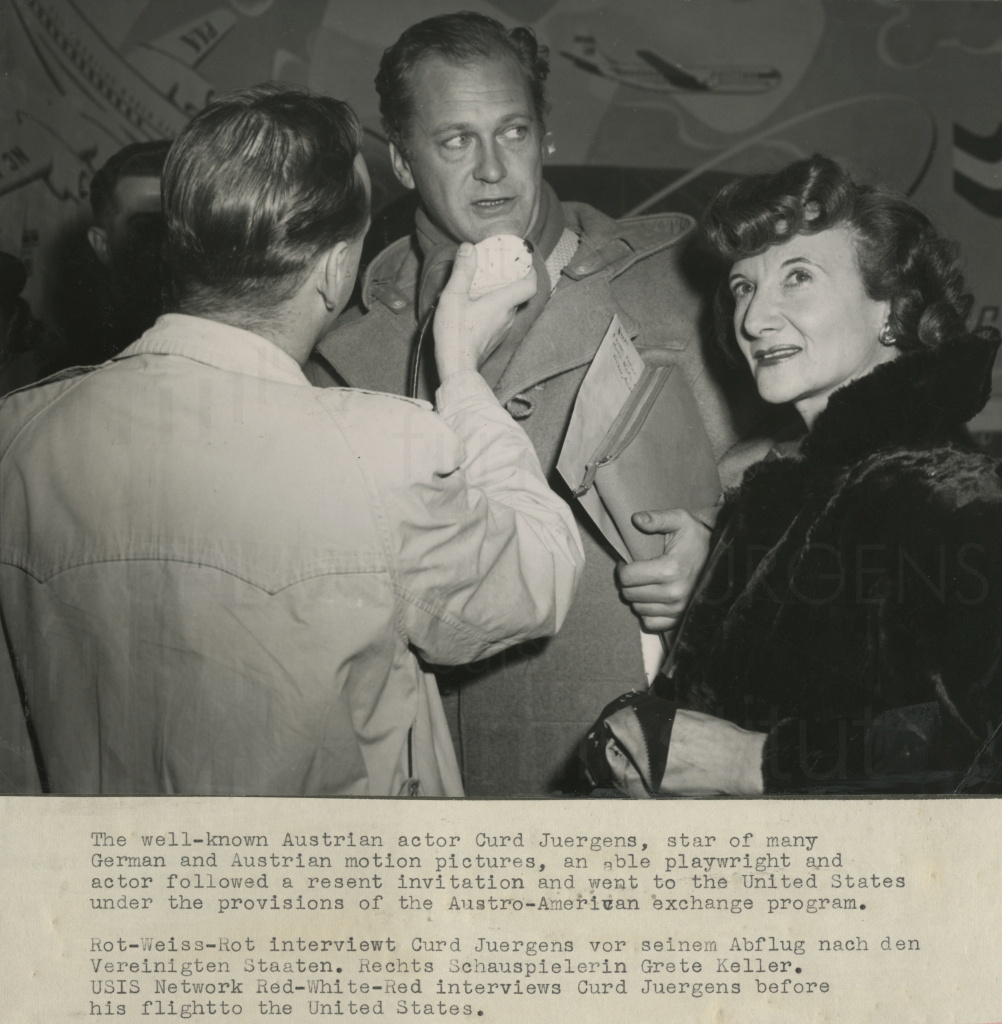

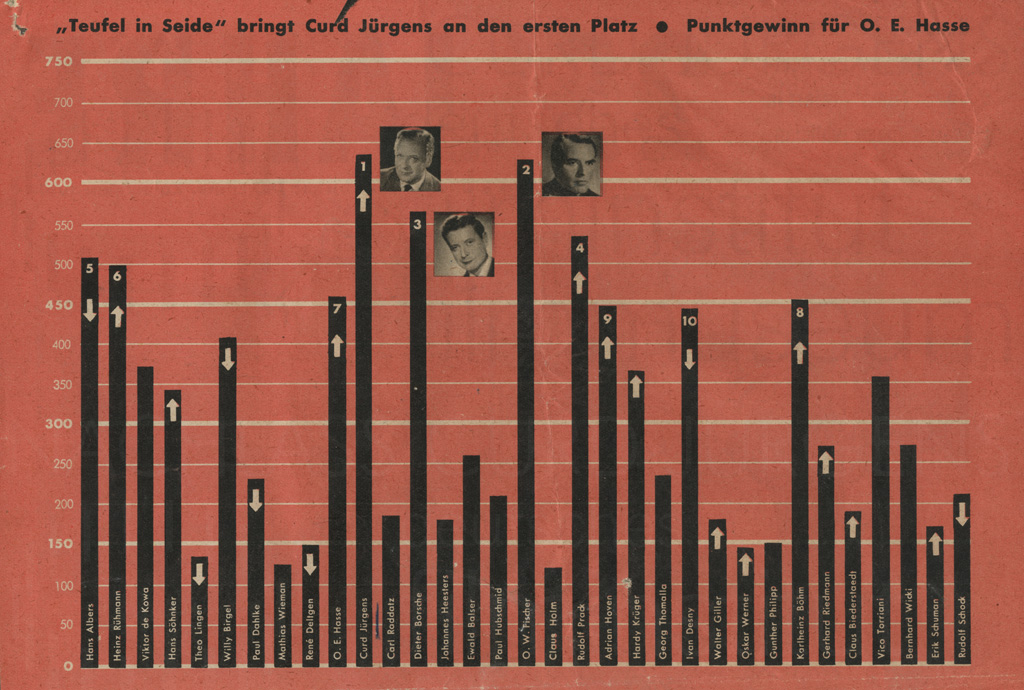

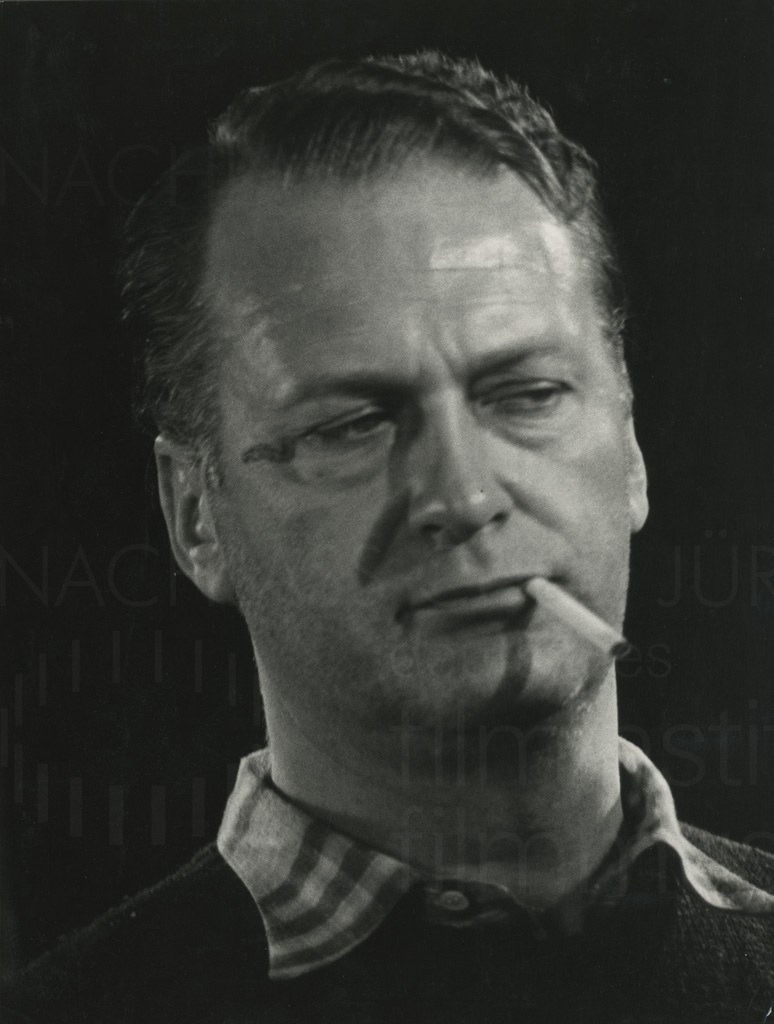

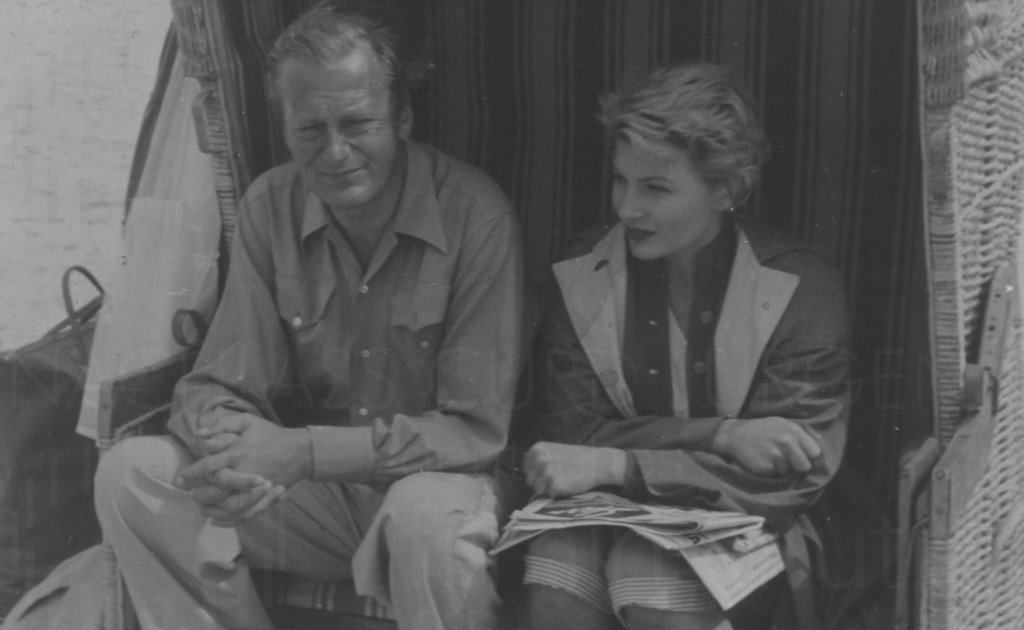

With Curd Jürgens, born in Munich, holder of an Austrian passport, living mainly in France, post-war West German film became international. Of all the male stars of this period, he is the one least identifiable with the cinema of the Adenauer era. He had nothing to do with the Heimat films which dominated West German cinema and comprised roughly one third of production output. He was never the male part of a “dream couple” which was so typical for the cinema of the 1950s. In 1950, the director Hans Deppe cast Sonja Ziemann and Rudolf Prack in his film Schwarzwaldmädel (1950) – and in doing so reached an audience, in the first evaluation, of 16 million) – O.W. Fischer and Maria Schell, Dieter Borsche and Ruth Leuwerik followed in the wake of the dream couple who fans affectionately dubbed Zieprack. Curd Jürgens acted with Schell twice – but without far-reaching consequences.

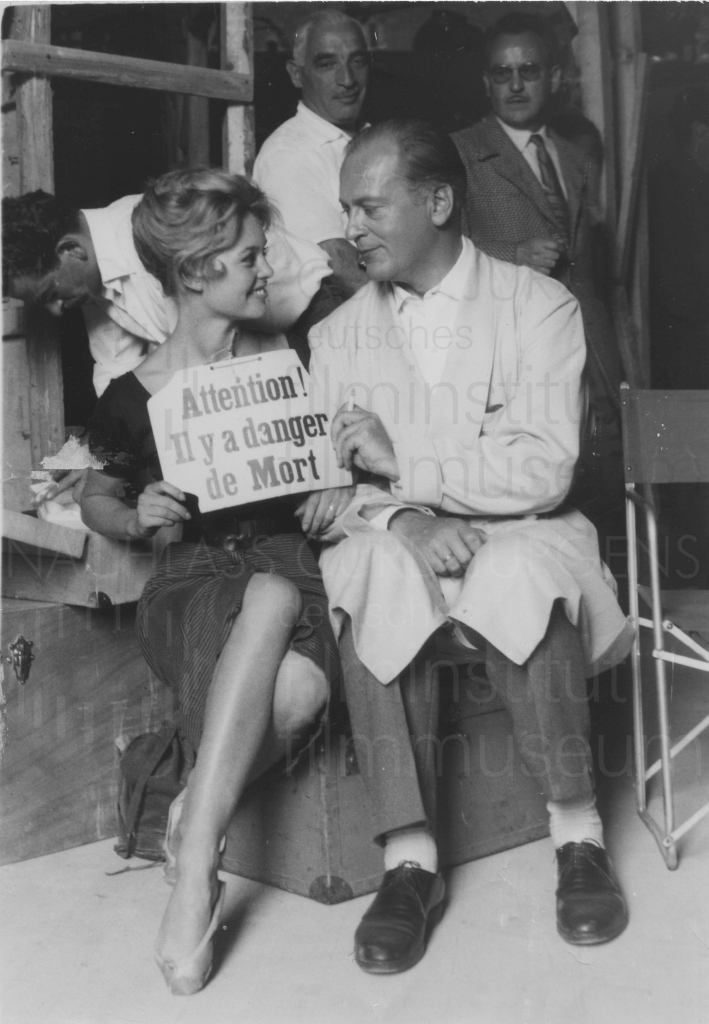

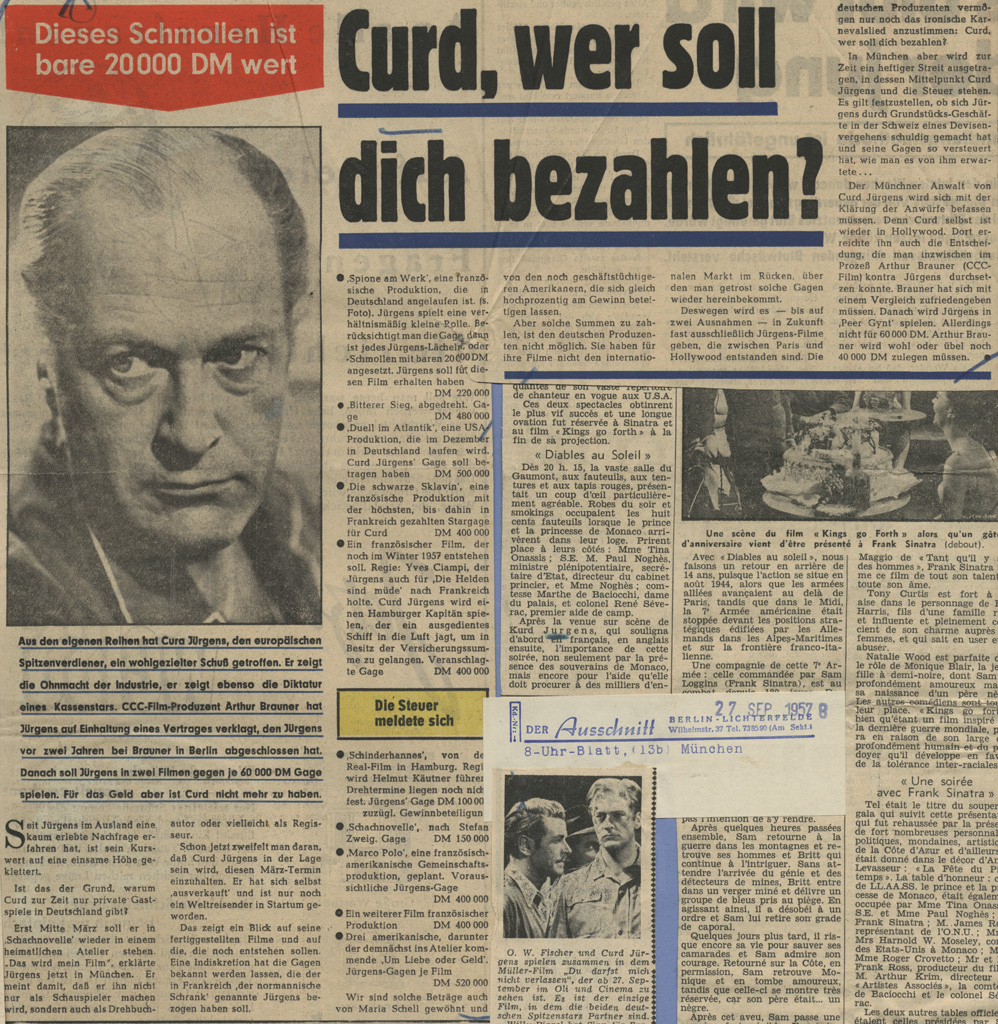

![N.N.: "Die Helden sind teuer", [1957]](https://curdjuergens.deutsches-filminstitut.de/medien/2015/10/1_8_1_Gagenstreit_1957_002.jpg)