CURD JÜRGENS AND THE YELLOW PRESS, PART 1

By Henning Engelke

By Henning Engelke

The gentleman is wearing a dinner jacket and white tie. A lady in a shiny silk evening dress with a fur cape over her arm is standing by his side – a typical photograph taken at balls and social events. In the image, the radiant couple are isolated from the crowd, their clothes and gestures characterise the type of function that is the reason for taking the picture.

The photograph described here was not a personal souvenir of a ball night; it appeared early in the summer of 1957 in numerous German, French and Italian newspapers and magazines: Curd Jürgens and Eva Bartok, the people shown in the photograph, had long since crossed the line where a picture like this would only be shown to a small group of friends.

When they met in 1953 while filming DER LETZTE WALZER (The Last Waltz, D: Arthur Maria Rabenalt), they were already both prominent film actors. The tabloid press was already at work: Eva Bartok had recently become famous as the result of a love affair in England and Curd Jürgens had become prominent not only for his film roles, but also for his two divorces. Their relationship was to overshadow all previous publicity. A love affair between two film stars: slapped faces in a bar, separation, reconciliation and marriage, and a matrimonial punch-up in a hotel in Rome, meant that they were constantly in the gossip columns in the newspapers. “Little Eva and Curd: the scandalous ones”, the magazine Quick wrotes looking back at the events.[i]

This cliché ended up in the film RUMMELPLATZ DER LIEBE (Circus of Love, 1954, D: Kurt Neumann), in which Jürgens plays an actor who beats up his wife – in the person of Eva Bartok. If contemporary reports are to be believed, the audiences at the première perceived the couple’s roles as being a mixture of the public and the cinematic, provoking strong hostile reactions to a scandalous life now exposed explicitly to public gaze on the screen. Their divorce in 1956 no longer came as a surprise for a public in the know.

What was a surprise was their amicable meeting during the Cannes Festival in 1957 when the two of them had only recently divorced – and it is this contact that finds a pictorially condensed expression in the photograph. The famous pair physically close to one another, smiling, but nonetheless non-committal, brought together at a social event. A small sensation with an unknown outcome, embedded in an emotionally laden context.

This is precisely what makes the photograph interesting for popular journalism: the emotional and the sensational have a much greater value in the selection a news item than is the case with serious journalism. Michael Haller introduced the concept of differentiating entertainment-journalism and serious-journalism, using an analogy with music.[ii]

Leaving aside the question of whether it was stage managed or not – the significance of this press-coup for Curd Jürgens was that he achieved additional coverage in the reporting at the Cannes Festival. That even without this occurrence he would have been the subject of reporting is not the question. The actor had become an extremely popular press topic, especially in the popular press. The photograph, which acquired a mass circulation, does not present Curd Jürgens as a private person – whoever and whatever that is – but the star in one of the roles out of which his public image is composed.

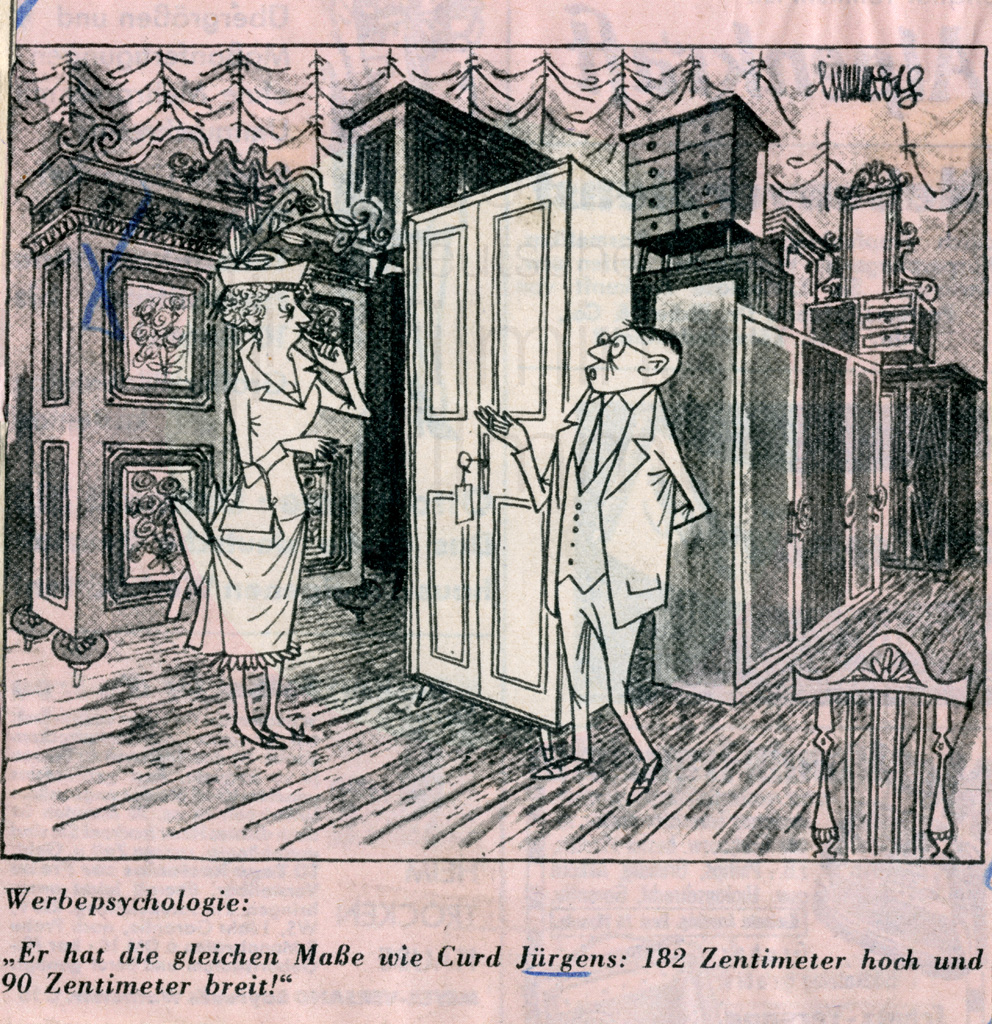

“Karikatur, dt., 1961

The formulaic classification of the star had an effect on his perception as a public person. A legendary remark coined by Brigitte Bardot[xii], relating to his physical attributes, characterises the role-image and the public image of the actor: “the Norman wardrobe”. This brand label will stick to him right until the end of his life and is used whenever it is necessary to give a pithy summary of his image.

In popular journalism there is also a constant blurring of the dividing lines between film role and public image, for instance when the Neue Revue in the above passage “in the midst of” the events in MICHEL STROGOFF sees Curd Jürgens and not Curd Jürgens as Michel Strogoff. Something of the adventuresome life of the hero is reflected in the public persona of the star. This process takes place, albeit for a different type of role, in the press coverage of the film TAMANGO (1958, D: John Berry). When the Münchener Abendzeitung quotes the actor as saying:”First of all, I have to get used to handling slaves, especially my favourite slave girl…”[xiii], the words are attached not to the character in the film but to the celebrity.

Furthermore, the statement is furnished with exotic charm by the slave girl being described in the next sentence as being “sultry-eyed, dusky and ravishing”. It comes as no surprise that the woman portrayed in this way, Dorothy Dandridge, had to defend herself strenuously against reports in the tabloid press that implied she was having an affair with Jürgens.[xiv] The image of strong hero combines with that of cinema heart-breaker who has women throwing themselves at his feet, both on the screen and in private – never mind the female fans.[xv]

The popular press, by acting in this manner, had the opportunity of exploiting every meeting with a female star – be it Ava Gardner, Sophia Loren, Brigitte Bardot or, as already mentioned, Dorothy Dandridge, into speculations about an affair and of substantiating it with reference to the pattern of seducer that a new report appears to confirm.[xvi] In any case, probability speaks for the press report, so that an article clearly entitled “New surprise in Venice: Romance Curd Jürgens – Romy Schneider” can only proceed as speculation and yet, by reference to the image, can appear to a certain extent plausible. “Heart-throb Curd Jürgens is said to have broken little Romy’s heart in Venice. (…) There will be a grain of truth in the story.“[xvii]

“Even after his marriage to Simone Becheron, Curd Jürgens is assigned the permanent role of seducer: “My husband, the heart-breaker”.[xviii]

Translation: Elizabeth Ward

Notes:

[i] Quick, No. 5, 1961, no page.

[ii] Michael Haller: Die Journalisten und der Ethik-Bedarf. In: M. Haller, Helmut Holzhey [ed.]: Medien-Ethik. Beschreibungen, Analysen, Konzepte für den deutschsprachigen Journalismus. Opladen 1992, p. 199. Although in the present essay Jürgens ‘role in the “U–journalism‘ will be examined, at some places will be made references on the organs of the” e-journalism “. Firstly, in contrast, on the other hand, because there are also categories and articles that can be added to the “U–journalism“.

[iii] Curd Jürgens in an interview with the Vorarlberger Nachrichten, 13.12. 1975.

[iv] Carlo Michael Sommer: Stars als Mittel der Identitätskonstruktion. Überlegungen zum Phänomen des Star-Kults aus sozialpsychologischer Sicht. In: Werner Faulstich, Helmut Korte [ed.]: Der Star. Geschichte – Rezeption – Bedeutung. München 1997, p. 114.

[v] Miriam Meckel: Tod auf dem Boulevard. Ethik und Kommerz in der Mediengesellschaft. In: M. Meckel, K. Kamps, P. Rössler, W. Gephart: Medien-Mythos? Die Inszenierung von Prominenz und Schicksal am Beispiel von Diana Spencer. Opladen 1999, p. 34.

[vi] Patrick Rössler: Und Diana ging zum Regenbogen. Die Berichterstattung der deutschen Klatschpresse. In: Meckel, Kamps, Rössler, Gephart, loc. cit., p. 101.

[vii] See Niklas Luhmann: Die Realität der Massenmedien. Opladen 1996, p. 28: „Vor allem ist die öffentliche Rekursivität der Themenbehandlung, die Voraussetzung des Schon-Bekannt-Seins und des Bedarfs für weitere Informationen, ein typisches Produkt und Fortsetzungserfordernis massenmedialer Kommunikation.“

[viii] 30.3.1957, no page.

[ix] General-Anzeiger, Oberhausen, 29.3.1957.

[x] „Curd Jürgens mit dem Helm und den grausamen Augen der Deutschen, mit seiner Göring-Ähnlichkeit …“ [Noir et Blanc, cit. and translated in Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung, 23.2.1957, no page]. In a reader survey of the French magazine Cine–Revue [1957] Curd Jürgens takes in yet the third place when asked about the most popular actor, behind Fernandel and Jean Gabin, still before Gary Cooper and Eddie Constantine. Jürgens had already become an Austrian citizen shortly after the war, but this was barely noticed in the press note. In the media, he almost always appears as German.

[xi] B.Z., 7.9.1957.

[xii] See Curd Jürgens: … und kein bißchen weise. Locarno 1976, p. 383. Neue Post has another explanation that puts the star in a slightly adventurous argumentation near a mythological prototype: „Das französische Publikum nennt den großen und breitschultrigen Curd: ‘Der normannische Schrank‘. Wohl in Erinnerung an jene blonden Seefahrer, die vor tausend Jahren das französische Herzogtum Normandie gründeten“, 30.3.1957, no page.

[xiii] Abendzeitung, Munich, 30.6.1957.

[xiv] Ed. Note: If you believe Curd Jürgens’ portrayals in his memoirs, the two actors in fact had an affair. See Jürgens, loc. cit., p. 397 ff.

[xv] Ici Paris published a [fictional?] fan letter in 1957 to Curd Jürgens which begins as follows: „Tu es beau, tu es grand et fort / tu es mon nord et mon sud …“, no page.

[xvi] „Wird Ava Gardner Ehefrau Nr. 4?“ headlines Bild-Zeitung e.g. in 1957.

[xvii] Der Erzähler. Österreichs älteste Wochenschrift, 23.9.1957, no page.

[xviii] Bild-Zeitung am Sonntag, 8.2.1959.